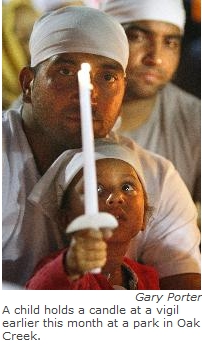

Last weekend, I had the unenviable task of teaching Sikh children about the massacre in Oak Creek.

Last weekend, I had the unenviable task of teaching Sikh children about the massacre in Oak Creek.

The kids sat at picnic tables overlooking a lake at sunset at a summer camp in New York state. They chattered excitedly in anticipation of the evening campfire that was to follow. I stood in front of them trying to compose my thoughts, wondering if children in elementary school could even comprehend what happened. I stroked my beard nervously, looked around the class and decided to find out what the kids already knew.

"Today, I want to talk about something really sad and important. How many of you know what happened in Oak Creek, Wisconsin?"

Dozens of hands darted toward the sky - each of the 40 kids had heard about the mass shootings. I asked for volunteers willing to tell the story, and 40 eager hands shot up again. A young boy in a shiny blue turban stated that someone went into a gurdwara and started shooting people. A girl in a green tank top confessed that she is "scared to go to gurdwara now because other people might try hurt us."

A third young girl, who had just lost her first front tooth that day, waited patiently for me to call on her. I finally pointed in her direction, and her words sent shivers down my spine:

"A white Christian man came and killed a bunch of us. He didn't like us because we are different."

In some ways, her innocuous statement was problematic and, in other ways, profound.

The second part of her analysis captured key aspects of the Sikh experience in America. We have been targeted because people have perceived us as being different. That's a simple fact.

On the other hand, the first part of her analysis was troubling. I was struck by her characterization of the killer and, for the first time, realized that we need to guard against the construction of white, Christian males as "the other."

How the tables had turned.

In order to make sure the kids weren't generalizing or stereotyping Christians, I called attention to one of the heroes of Oak Creek, Police Lt. Brian Murphy. In pointing out that he was also a white, Christian male, I was able to effectively communicate the problem of projecting individual actions onto larger communities.

The young Sikhs grasped the importance of this point more quickly than I expected, and, in retrospect, I realize that this is probably because of their own experiences in being bullied and harassed.

After ensuring that the kids understood this elementary point, I moved on to a more challenging idea.

"In Sikhi, we believe that God is in everything and everyone. Has anyone heard that before?"

All the kids confirmed my expectation by nodding their heads in unison. I asked them to give me examples of where God is present, and they pointed to the nature around us, including trees, lakes and ducks. I asked about mundane objects in direct sight, such as benches, pencils and plastic cups. The kids were sharp - they quickly got the point and exclaimed excitedly: "Oh, yeah! God is in those things, too, because God is everywhere!"

I explained that recognizing God's presence everywhere means that Sikhs are expected to love everything and everyone equally. I asked the students to look in each other's eyes and try to see God in each other. It was beautiful to see their eyes light up with newfound enthusiasm and respect.

Then came the hard part. One of the more thoughtful students raised his hand with a confused look on his face.

"If you say God is in everybody, are you saying that God was even in that man who killed the Sikhs in Wisconsin?"

I loved the question, which reflected the same sort of compassion, discontent and critical engagement, expressed by people of faith around the country. The entire class had fallen silent, and I could see the boys and girls struggling to make sense of it all.

I encouraged them to think about it for half a minute, and they came up with an impressive range of critical thoughts. Their responses essentially fell into two categories: Some believed that the shooter did not have any God in him, and others believed that he did.

One 11-year-old raised her hand shyly and nervously adjusted her pink-framed glasses as she spoke: "I believe the killer had God inside of him, but he chose not to listen to God and so he did a bad thing. He didn't see God in other people, and that's why he could hurt them."

Her answer touched me to the core - she had articulated my understanding of Sikh theology more simply and precisely than I could have ever imagined.

I can only imagine what our world would be like if we were as mature as this 11-year-old, wise enough to distinguish between people and actions. She echoed the Sikh theological perspective that our enemies are not particular individuals or peoples; rather, we seek to eradicate human tendencies that bring suffering in this world, such as ego, greed and anger.

I explained to the class that although Wade Michael Page did a terrible thing by hurting so many people, Sikhs believe that he still had God inside of him.

Speaking to the children raises an important issue for us to consider. The challenge for Sikhs is to determine how we will react to Page and others who commit hateful acts. How will we respect the godliness in our greatest foes, and how will we teach our children and younger generations to accept and grow after such devastation?

This perhaps will be our greatest obstacle in the months and years to come.

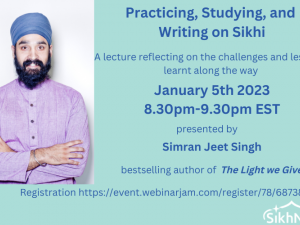

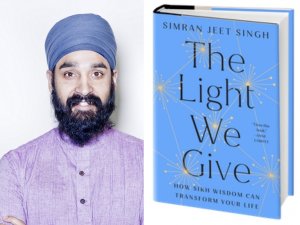

Simran Jeet Singh is a doctoral candidate in religion at Columbia University.