There is a concept in Western psychology called the “Persona.” It resembles, but not necessarily equals, the Eastern concept of “Face.”

In Eastern thought, “Face” is something people are aware of. While in Western psychology, the Persona is something that operates more at a subconscious level. Both result from the same basic human tendency - our need to be acceptable to and accepted by the community in which we belong.

It is an aspect of human survival. Ernest Hemingway famously said, “No man is an island, entire of itself.” We need each other to live. How we view and communicate with one another, share internal and external resources, is critical to our shared success as a species.

All of us have certain talents, tendencies, gifts, strengths and vulnerabilities. As we mature, we go through a sorting process where we assess ourselves, based upon the reaction of our caregivers: parents, uncles, aunts, grandparents, teachers, mentors, role models, bosses. The character traits that they mirror back to us positively, we cultivate and share openly. This becomes our presentable identity, the identity that gives us a sense of acceptance and belonging, which we need to survive and to thrive.

At the same time, the shadow represents a broad set of character traits that none or very few of our social communities find acceptable. When our social circle mirrors those character traits back to us in a negative way, we suppress them. First we hide those traits from others. Eventually, we can even hide them from ourselves - through the emotion of shame. Yet, even if those traits remain buried beyond our conscious perception, they exist nonetheless.

Inevitably, different types of people respond in different ways to the character traits and talents that we carry.

A lawyer may be valued for his or her acumen, intelligence and ability to reason and debate. But on the weekends, or during “free” time, that same lawyer may enjoy painting, a much more solitary and visual endeavor.

A wife and mother may be appreciated for her wonderful cooking. But she may also find fulfillment through community activism, engaging with like-minded people on issues of political or social importance.

So the “persona” or “face” is not strictly definable. It involves a dynamic where different aspects of our social networks positively reflect back to us a subset of characteristics, although no one social network may positively reflect all those characteristics. In that regard, each of us collects many satellite communities that we dance with, in the orbit of our existence.

All of this begs the question - what, then, is a Guru? A Teacher? A Guide? Is it someone who becomes yet another reflection in our lives of the parts of ourselves that are acceptable versus unacceptable? Who gives us the line where we use an internal razor blade to excise certain aspects of ourselves, which have been declared, once and for all, “unfit”?

Or is the darkness that the Guru seeks to lift us from actually the darkness of our own shame? Shame, which the psychologist Carl Jung once called, “The swampland of the soul”? Does the Guru help us overcome the darkness of self-blindness and denial, where we internalize the negativity of others, and in time reject aspects of ourselves?

In short - does the Guru make us holy? Or does the Guru make us whole?

Since April/May of 2016, the Universe has given me the unique and challenging gift of walking deep into my own swampland. As painful as this process has been, I have discovered that the Guru has not only stayed with me throughout it, it turns out that the Guru pushed me into the swamp to begin with.

This formidable journey has brought me face to face with the darkness in myself. As well as the rather curious experience of being caught in the cross winds of two very different cultural interpretations of that darkness. There is the psychiatric diagnosis of depression which talks about trauma, childhood wounding, imbalances of brain chemistry, medication and therapy. And then there is the spiritual diagnosis of “the dark night of the soul,” a phase of spiritual development where a devotee becomes unable to access a previously available mystical reality. And the resulting tastelessness of life that results from losing that access.

Add a good old fashioned mid-life crisis into the mix as my body enters menopause and let’s just say the last two years have been a time of terrifying, fascinating and profound change.

Through it all, the Gurmukhi term ‘Vairaag’ (sometimes referred to as Bairaag) has kept calling to me. I would like to appreciate Yogi Amandeep Singh who first acquainted me with this term. And also appreciate Dr. Kirpal Singh who graciously shared many hours of his time discussing Sikh stories with me that illustrate the state of Vairaag.

Through it all, I have felt the hand of the Guru asking me to come to a different understanding of my own darkness. To enter into a different relationship with it. An invitation to find a sense of peace and comfort with myself, with all of myself, even the most unacceptable aspects.

In seeking to study this stage of Vairaag, I have turned to the two tools that have helped me the most when translating Gurbani. The first tool is to examine the term according to its more fundamental sound-meaning units.

B/Vairaag

B/Vai Raag

B/Vai - for the purpose of this exercise, I am going to propose that the (B/Vai) in B/Vairaag is actually a variation of the negating prefix B/Vay. In The Punjabi Dictionary first printed in 1895, the entry for Bay is over a full page. Yet the essence of the prefix is a negating one. To negate, to void, and to make opposite the meaning of the syllable(s) that comes next.

Raag - Divine scale. Love. Attunement.

From this analysis, one possible definition of Vairaag is: becoming void and not being able to experience loving attunement with the Cosmos.

My hypothesis is that even though Vairaag gets translated as pure devotion, it actually means the opposite.

It is that experience of the VOID, of the DISCONNECTION from Raag - from the Love, from the Divine Harmony - that sends one into a desperate search. The disconnection that Bairaag implies creates the longing to abandon everything - life, reason, normal social reality - in order to look for it, or find it again. It is a kind of spiritual insanity, or spiritual depression.

If we look at spiritual depression as a necessary stage in the journey of spiritual maturity, then B/Vairaag happens when the spiritual persona breaks. Just as we develop a social persona to get along in our social life, it is very human to develop a spiritual persona in the midst of a spiritual community.

In sangat, we take cues from others’ reflections of us to subconsciously sort which of our gifts, talents and traits are acceptable, and which are not. This gives us a sense of how to be accepted by our spiritual community, and results in the formation of a spiritual persona.

Yet, there comes a sacred moment when the Guru uses our love, our faith and our attachment to set us up so our spiritual shadow becomes visible to us, and our shame gets revealed. As painful as this moment of naked exposure can be, it also provides the Guru an opportunity to take us on the journey to authenticity and wholeness.

But what does that look like, on a practical level? This is where the second tool to understand terms in Gurbani arises. Looking at the stories handed down through the generations, that illustrate the state of Vairaag and how it manifests in a person’s life.

The first story I would like to explore in this regard is the story of Bhai Joga Singh.

It is said that, as a young boy, Bhai Joga Singh’s parents brought the family to the court of Guru Gobind Singh, where they spent some time there. Bhai Joga had a radiance about him, and dedicated himself to serving langar and to helping clean up after the sangat ate. The Guru noticed this young boy who served langar with such dedication and devotion. One day, the Guru approached Joga and asked his name.

“Ji, Joga,” came the reply.

The Guru then teasingly asked him, “And who are you joined with?” playing off the boy’s name.

And the young boy responded, “Ji - Guru Joga.” Joined with the Guru.

Without hesitation, the Guru joyfully replied, “If you have joined yourself to me, then I join myself to you, as well.”

Guru Gobind Singh embraced the boy and asked his parents if they would leave their son to his personal service. His parents agreed, and young Joga grew up in the Guru’s home. He learned about the path of Guru Nanak directly from the Tenrh Master, and he became a trustworthy and reliable member of the Guru’s staff.

After many years, Bhai Joga Singh had earned the respect of the sangat. The Guru had entrusted him with various responsibilities and he had a reputation as a true GurSikh. In time, Bhai Joga had grown to a marriageable age. His parents wrote a letter to the Guru, saying they had found a suitable match for their son, and requested permission for the young man to return to his parents’ home for his Anand Karaj.

The Guru agreed, but on one condition. That Joga would return immediately to Anandpur Sahib, wasting no time at all, should the Guru send a message asking him to come back. The young man agreed, and set forth for his wedding.

I would like to pause here and point out that this is the moment of the spiritual set-up. There comes a time when the Guru, from love and a sense of responsibility, has to set the student up to show them their shadow-self and help them engage and make peace with their shame.

In order to do this, the two need a practical bond of love and trust, of command and obedience. There needs to be a history of fruitful learning experiences between the two before the Guru can take his student into the VOID - where the Shadow, or Hidden Self gets revealed.

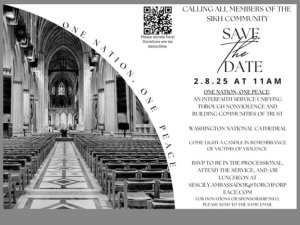

The Header Pic: Dawn ~ The Bhai Joga Singh Gurdwara in Peshawar, which remains home to a small Sikh community

Read Part II here