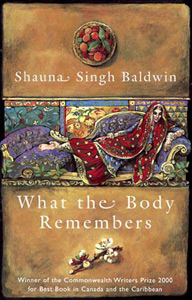

A powerful literary voice rising from North America but echoing worldwide, Shauna Singh Baldwin gives us widely diverse characters who enable us to understand the similarities we all share. Her novel, What the Body Remembers, published in 2000, won the Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best Book, and her second novel, The Tiger Claw, published in 2004, was nominated for the Giller Prize. Baldwin's second short story collection, We Are Not in Pakistan, has recently been released. Her first story collection, titled English Lessons and Other Stories, depicts the struggles of immigrant Sikhs. It won the Friends of American Writers Prize.

A powerful literary voice rising from North America but echoing worldwide, Shauna Singh Baldwin gives us widely diverse characters who enable us to understand the similarities we all share. Her novel, What the Body Remembers, published in 2000, won the Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best Book, and her second novel, The Tiger Claw, published in 2004, was nominated for the Giller Prize. Baldwin's second short story collection, We Are Not in Pakistan, has recently been released. Her first story collection, titled English Lessons and Other Stories, depicts the struggles of immigrant Sikhs. It won the Friends of American Writers Prize.

Shauna and her husband, who live in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S.A., own Safe House - a spy-themed restaurant.

THE INTERVIEW

Rosalia Scalia [RS]: Sikh men usually take the common last name Singh (lion) and Sikh women usually take the common name Kaur (princess). How did you come to have Singh as part of your name?

Shauna Singh Baldwin [SSB]: I lost my family name when I married out of community, and wanted to retain a connection to my heritage. I am no princess and wasn't being treated as one (smiles), so it didn't seem as if Kaur fit. I took Singh to make myself feel more like a lion. As the guru intended, it reminds me daily that I should be courageous not only for myself but for others.

RS: Was there a lot of family angst when you married a non-Sikh, non-Indian man?

SSB: Not angst, anger and hurt. I was a reluctant rebel. I had expected an arranged marriage, but didn't find the men my family chose appealing, and wanted to stay in Canada. I also didn't want children, and unfortunately the arranged marriage system is just not set up to accommodate such a choice for a young woman. (I'm not decrying the institution - it's a godsend for men and women who don't enjoy internet and pub-dating. It spares you personal rejection and pressure to become a sexual being in your teens.) Soon after that, I decided to follow my heart. Which meant renouncing the support of many family members and friends, and learning the culture and traditions of an Irish-American family.

RS: You are one of the few Sikh-American or South Asian writers who write Western women characters with compassion. This was especially remarkable and poignant in the title story in English Lessons. The Indian wife in that story shows tremendous anger toward the American Green Card wife who continues to call, long after the man has left her; the Western woman whom the Indian wife hates so much is obviously feeling a lot of pain. Could you talk about that story?

SSB: Thank you - I'm so glad you felt the pain of both women. The story came from my experiences as an ESL (English as a Second Language) teacher, at first for people in my own community. It was about being a Sikh in the late '80s, when Sikh men in Punjab were automatically labeled terrorists and targeted by the Indian police. An already difficult situation became more so for immigrants who were just trying to get by.

Baljit in "English Lessons" is doubly preyed upon. And comparing India and the USA, finds she really hasn't come to a better place. I admire her for making the best of a bad situation. She's angry at the Green Card wife, because it's so much easier to blame the person who is distant, rather than to direct her anger toward her husband, where it belongs. Both women - the Green Card wife and the Indian wife - are used.

Baljit in "English Lessons" is doubly preyed upon. And comparing India and the USA, finds she really hasn't come to a better place. I admire her for making the best of a bad situation. She's angry at the Green Card wife, because it's so much easier to blame the person who is distant, rather than to direct her anger toward her husband, where it belongs. Both women - the Green Card wife and the Indian wife - are used.

Recently, in real life (or should I say, surreal life?), I met an Indo-American woman abandoned in the new country after thirty years of marriage and three children. She is constantly being told by her husband's new "wife" - "My husband didn't choose you!" As if choice or the lack of it excuses their common husband his bigamy.

RS: It seems as if every woman in English Lessons is an "adjustable woman", not just the characters in the story, "Nothing Must Spoil This Visit", where the term appears, but all of them.

SSB: Funny you say that - I nearly named the whole collection "Adjustable Women".

RS: It seems that Indian culture fosters conformity.

SSB: No, Indian culture does not foster conformity - individuals who exert power demand and enforce conformity. Please let's not forgive ourselves so easily. Let's not do the usual nice little dance around the fact that individuals - not systems, not cultures - foster conformity. Individuals assert power, and others go along with it because of economics. And if the price is high enough, a man or woman acquiesces.

Women at similar socio-economic levels, pay similar prices whether we are chopping wood in the developing world or living in a McMansion in the developed world. Economics motivates our choices, especially when children must be considered. Justice and economics are thought of at family level, because women are considered property - by individuals, not by a culture. In every situation, we need to ask the price of a woman's nonconformity - and across societies. And then we need to work to reduce it.

RS: How has your background in business influenced or informed your characters?

SSB: I think economics - power and money - is built into motivation. Desire is the life-blood of story, and economics drives not only characters but people in real life. How is power used? Follow the money and it often becomes clearer. For instance, I hear so often that women are passive, after all, why don't they leave in certain circumstances? But those logical decisions are based on economics, whether a Hillary Clinton makes them or a woman suffering from domestic violence in a developing country. People are not stupid. If we follow the economic logic and look at all factors that go into decision making, we find women make sensible decisions, not only for their own sakes, but for the security and well-being of their children.

In business, we use a lot of either/or thinking - I win/you lose. It works for a few. But to make it work for many, we need to toss the either/or language and fall in love again with the word "and" - I win AND you win.

RS: Give an example?

SSB: Carol Gilligan tells [i] how she was researching boys and girls' decision making and discussed the Aesop fable in which a homeless porcupine moves into a mole hole. The porcupine starts to move around, pricking all the moles. And Aesop's moral is that you should know your guest before you invite him in. But Gilligan asked the children to decide: what should be done about the porcupine?

The boys said: throw the porcupine out - the hole belongs to the mole, they said. The girls said: find a blanket to cover it so it can't hurt the moles and then they can all have shelter.

The girls' decision-making goal was to accommodate all needs. Theirs is the logic of the future. Linkage and connection, interdependent relationships and interrelationships. Unless we - meaning both men and women - begin to think in ways traditionally denigrated as feminine logic, our planet and our species won't last much longer.

The girls' decision-making goal was to accommodate all needs. Theirs is the logic of the future. Linkage and connection, interdependent relationships and interrelationships. Unless we - meaning both men and women - begin to think in ways traditionally denigrated as feminine logic, our planet and our species won't last much longer.

RS: In What the Body Remembers, you explore the institution of polygamy. Tell us how it came about and what you think of it?

SSB: My friends and I sometimes joke that any wife who works in or outside the home, whether living in the West or the East, could do with a wife. We say, Wouldn't it be wonderful if we all had wives - someone rotating around us, intuiting our every need before it is expressed, taking care of activity scheduling, meal planning, travel arrangements, disaster prevention great and small?

But joking apart: in societies that have social security (which means Western "developed" societies) when a man wants a second wife, he negates his agreement with his first wife, and then the state essentially becomes the first wife's husband. The state becomes responsible if she loses a job, if she remains unemployed, if the children go hungry. In old age, even if remarried, she receives benefits from the state. Widows too, receive pension benefits from the state.

Not so in the developing world, even today. Men and women in countries like India still have no social insurance. There's no disability care, no Medicare, no Medicaid, no Provincial HIP. And there are no IRAs, no CPP, no RRSPs. The public health system is in an abysmal state. All you have is your family - the clan, the tribe. Which means that power in most non-Western countries rests with the traditional breadwinners/property owners - men.

Polygamy in the ruling classes was instituted for peacemaking alliances. It spread to upper classes so indigent women and war widows would find benefactors, men generous enough to take them in. Over time, this institution set up for the purpose of helping women turned exploitive.

It was banned in India in 1956 for Hindus and Sikhs (though it's still legal for Muslims). It has been banned in many countries, but it's still happening - in the US, as of 1997, the New York Times estimated 60,000 women were living in polygamy.

In a story, I'm interested not in the institution, but in the way social and economic power is used and felt by characters who find themselves within it.

RS: What the Body Remembers is about the Partition.

SSB: Yes, a horrific event that occurred in August 1947 along with India's independence from Britain. Five million people died (in both India and the then newly-carved Pakistan) and 17 million were displaced in their own country. To this day "Happy Independence Day" remains unspoken in so many Punjabi and Bengali families - they mourn those who paid for Independence. And there are no official memorials yet, in either India or Pakistan.

RS: Did you cry while writing that book?

SSB: It seemed I had a faucet inside. But I kept a note pinned to my desk as my talisman - a quote from Toni Morrison, "You only have to write it, they had to live it".

RS: How do you come to a story?

SSB: Usually, I start from a voice. Someone is bothering me, saying, "Tell my story!" or just talking. Sometimes, I get an image or a dream. If the image or dream keeps coming back, I need to explore the story by writing.

RS: There aren't many women Sikh writers. Why?

SSB: Several Sikh women write in Punjabi, but not enough have been published, and of those published, few have been translated into English.

Do you mean why haven't there been more Sikh women writers? For many Sikh families, fortunes had to be rebuilt after Partition. My grandmother and mother's generation did not have the time, the money or husbands kind enough to say, "Oh, are you going away for four-five months to write, leaving our children behind? No problem, I'll look after them", Even today most of us are super busy making three meals a day, working in fields and/or offices, and looking after husbands and children.

And writing is an elitist sport. One needs time to write, and patronage (otherwise known as money). Patrons like the Canada Council, awards from the CBC and The Writers Union of Canada, several grant donors and writer's residencies have given me support and encouragement.

But as for women Sikh writers in English: we're getting to it - we've begun!

RS: Has being involved in your husband's spy-themed restaurant inspired any of your work?

SSB: Certainly. It was at the Safe House that I heard the tale that became The Tiger Claw. A customer and only true secret agent we know, Gaston Vandermeerssche, was writing a memoir of his leadership role in the Dutch underground, Gaston's War. Gaston sent me information about Noor Inayat Khan. I was horrified by the orientalism and male fantasy with which her story had been told. Noor was a radio operator and a nurse, but had been portrayed as a flighty oriental woman who was either oversexed or enigmatic. I felt her story needed to be retold from her point of view. So I traveled to Europe to find out more about her and read many books about WWII. And I wrote as a Sufi Muslim, which was Noor's religion. That meant suppressing the Hindu aspects of my faith, Sikhism.

Baldwin is working on her next novel. More information at http://www.shaunasinghbaldwin.com/

Footnote 1: In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development, by Carol Gilligan.

BOOK REVIEW: WE ARE NOT IN PAKISTAN

A Book Review by ROSALIA SCALIA

With two novels and two short story collections, Shauna Singh Baldwin has emerged as one of the most compelling literary voices in recent times.

Born in Canada (Montreal), raised in India (New Delhi), now living in the United States (Milwaukee, Wisconsin), Shauna - who says in an interview with Quill and Quire that she thinks in English, in Urdu, in Punjabi and in French - culls from her keen observations of the world and people around her to conjure a plethora of characters that speak to us all.

Shauna's ability to think in multiple languages has translated into an ability to create multicultural characters with compassion and to explore their worlds with artistry.

This is most apparent in her latest short story collection titled, We Are Not In Pakistan. Characters in the collection's ten stories hail from Ukraine, Central America, Pakistan, Los Angeles, Mexico, Costa Rico. They are old, young, rich, poor, and of an array of religious backgrounds.

For example, Fletcher, the character in a story titled with the same name, is a Llasa Apso.

While the diversity of the characters reflects Shauna's global perspective, what the collection demonstrates is that despite the diversity, characters are connected by their humanity, by their flaws, by their fears, by their desire for love, for forgiveness, for connection even when working hard to maintain isolation.

The opening story, "Only a Button", takes on the after effects of the Chernobyl from the point of view of Olena, whose husband works at the nuclear plant during the explosion. Olena's husband and child evince the signs of radiation poisoning, signs that improve once the family - including the mother-in-law - moves to the United States, but along with the radiation poisoning, an old hurt between Olena and her mother-in-law festers and poisons their relationship.

The story "Fletcher", told in part from the point of view of a dog as well as from the perspective of others in a series of monologues, explores the desire for love and connection, between lovers, regardless of their sexual orientation, between a dog and its owner, between relatives, and the risk of loss inherent in the act of seeking that connection.

Fletcher's owner, Colette, and her boyfriend Tim do make it to the altar at the end, but it took the suicide of Colette's renter Martin, which subsequently nearly caused her own death, for Tim to realize how much she means to him.

In the title story, "We Are Not In Pakistan", 16-year old Kathleen hates her Pakistani grandmother for her Old World ways, and later values her grandmother and those same ways, offering a modern and fresh illustration of the warning, "Be careful what you wish for, it may come true".

In the most memorable, poignant story, "The Distance Between Us", Shauna brings together a Sikh man named Karanbir - a college professor in California - with a daughter he didn't know he had, the product of his only marriage, a two-year-long union to a Western woman for Green Card purposes - at a time when both father and daughter find themselves alone in the world.

Shauna's stories not only embrace diverse characters, but also diverse narrative styles. In the story "Naina", she uses magical realism to depict fear. Naina is pregnant with a daughter who refuses for 14 years to be born. Moreover, Shauna is not afraid to explore large world events such as 9-11, terrorism, nuclear meltdowns, political upheaval and their impact on innocents left behind in their wake.

We Are Not in Pakistan is a must read for anyone endeavoring to be a student of human nature and a citizen of the world.