Baltej Dhillon couldn't help but pay Shoulder to Shoulder Militaria & Collectibles a visit after his son-in-law told him what he'd seen inside on a trip to Calgary in late 2019. A number of pins were kept behind a glass display case. They had been made thirty years earlier, when Dhillon was embroiled in a heated national controversy over whether the RCMP should permit Sikh officers, like him, to wear turbans while on duty.

“Keep the RCMP Canadian” was written across one pin that included a picture of a Mountie wearing a turban. Another pin featured a Mountie riding a camel while wearing a turban. "Canada's New Musical Ride" was written on the label.

Dhillon grabbed roughly $50 worth of the pins after being shocked to see that these "symbols of hate" were still in use. He claims that when he went to pay for them, the store's owner showed a hint of embarrassment.

“I am grateful to live in a country where expression is part of our freedom. Propagating hate, however, is not.” he told the Star.

Sparking debate for religious rights

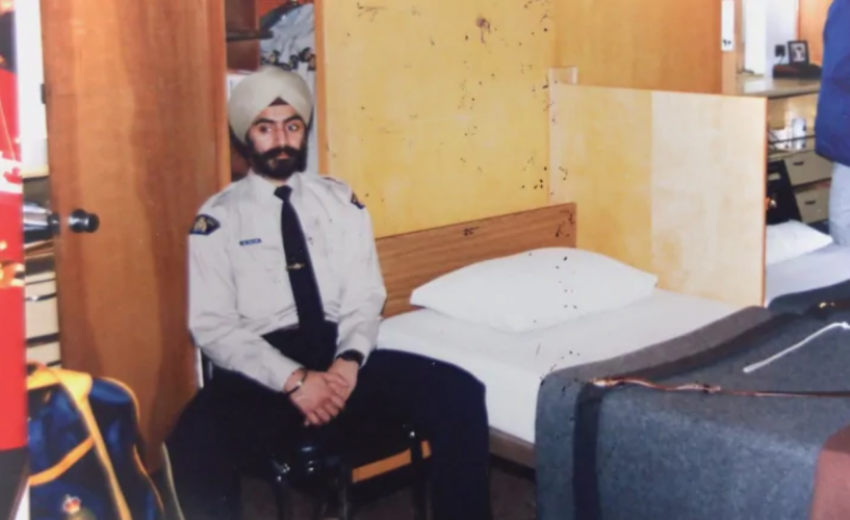

May 2021 commemorated the 30th anniversary of Dhillon's RCMP training academy graduation when he made history by being the first Mountie to be permitted to wear a turban while on duty. Some may find it startling to consider that something so basic could cause controversy in 2021, but the change in uniform policy sparked a spirited debate about what Canadian identity means as well as petitions and legal challenges to keep traditional elements of the Mounties' uniform, like the Stetson hat.

According to Dhillon of Surrey, British Columbia, there is no denying that sentiments have changed over the past three decades, many things have not.The Star recently learned this when it spoke to some of the people who fought against his right to wear the turban while in uniform three decades ago.

For his part, Dhillon stated that there is still much work to be done in "finding kindness and compassion in how we interact with one another." He cited the continued distribution of the pins, the recent discussion of whether or not people should be permitted to wear face coverings during citizenship ceremonies, and Quebec's ban on government employees donning religious symbols as examples.

He said, “We need to continue to be vigilant because that hatred is just in the shadows.”

Dhillon’s journey as the first turbaned Mountie

In 1988, Dhillon was in his early 20s and trying to determine his life goals. He applied to become a Mountie after taking a part-time job as a jail guard for the RCMP. He successfully completed the initial application process, but he was unable to progress forward because he refused to abide by the RCMP's uniform regulation, which required him to take off the turban he had been wearing since he was 12 years old.

Born and raised in Malaysia, where it was customary to see Sikh officials in law enforcement and the military, Dhillon claims he was unaware of the impending "big national discussion."

Norm Inkster, the commissioner of the RCMP at the time, suggested to the federal government that the dress code be changed to let Mounties don turbans as part of their uniforms in the spring of 1989.

Petition for distinctive heritage rights

Kay Mansbridge, Dot Miles, and Gen Kantelberg, three sisters from an RCMP family in Calgary, started a petition for the protection of the "distinctive heritage and culture of the RCMP."

Mansbridge told the Calgary Herald at the time that when other minority groups claimed the right to wear their cultural attire, "chaos" would ensue. The sisters argued that their petition, which garnered over two hundred thousand signatures, was not motivated by racism.

Bill Hipson and Peter Kouda, two Calgary business owners, reportedly began mass-producing lapel buttons that mocked Mounties wearing turbans.

One of Kouda's pins wound up in the Galt Museum & Archives collection in Lethbridge. It depicts a Caucasian man surrounded by three visible minorities with the text, "Who is the minority in Canada?"

Dhillon stated that he could no longer be the "silent candidate" as the controversy developed and the discourse deteriorated into hostility.

Louise Feltham, an Albertan member of the Progressive Conservative Party, questioned at the same discussion, “If you make an exception for one group of people, where do you stop? Today’s uniform depicts neutrality, impartiality, tradition, history and heritage.”

In March 1990, however, the government under the leadership of Brian Mulroney declared that the dress code amendments would be implemented, and an application form was prepared for Sikh personnel who wished to be excluded from the conventional headgear.

In May of 1991, Dhillon graduated from the RCMP training academy and began working at the RCMP station in Quesnel, British Columbia.

At the time, community reception was mixed. When he entered bars to do sobriety tests, he was hailed as a hero. In some instances, he was met with booing.

Dhillon reports that his staff sergeant greeted him coldly on his first day of work, but when he left a few years later, he said, “You're like a son to me.”

Meanwhile, a group of retired Lethbridge Mounties, including John Grant, Kenneth Riley, and Howard Davis, along with Kay Mansbridge, filed a lawsuit seeking an order prohibiting the RCMP from permitting the wearing of religious symbols and a declaration that the commissioner's actions were unconstitutional.

According to court documents, the plaintiffs argued that when a religious sign is permitted to be a part of the RCMP uniform, the appearance of neutrality is compromised. Outside of the courtroom, the plaintiffs employed much less formal language.

The defendants stated that the uniform policy change was intended to remove a barrier to the employment of Sikhs in the RCMP and to reflect Canada's multiculturalism.

In 1994, the Federal Court dismissed the claim, stating that there was no proof that anyone had been deprived of their liberty or security by RCMP members wearing turbans, or that they had had a genuine fear of bias. The ruling was sustained by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. The plaintiffs brought the case to the highest court in Canada, which refused to hear it.

After participating in high-profile investigations such as the Air India bombing and the serial killings of Robert Pickton and developing expertise as a polygraph examiner and interviewer, Dhillon retired from the force in 2019 and assumed a new position as a staff sergeant with B.C.'s Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit, supervising a programme designed to reduce gun violence.

Prior to his departure, the RCMP relaxed some of its uniform and clothing regulations, permitting members to wear their hair in a bun, ponytail, or braid, to grow out their beards, and to display tattoos. Dhillon applauded the move that removed the requirement that members have to seek exemptions to wear faith-based headdresses, such as turbans and hijabs.

Another thing that has given him cause for optimism is the number of individuals who approach him during his engagements in public speaking to tell him that they had been against the uniform accommodation in the past but that they have since changed their opinions about it.

“That’s the hope — that there’s opportunity for people to grow,” he said.

According to Dhillon, who is a member of the RCMP, he believes that there are currently a few dozen members around the country that wear turbans. Since then, a significant number of the individuals who played a leading role in the campaign against the RCMP's uniform change have unfortunately passed away. Nonetheless, The Star was able to communicate with a few of their surviving family members.

According to John Mansbridge, who is the son of Mansbridge, "the sentiments of thirty years ago do not always correlate with some of the thinking of today."

Still keeping the shadows of past alive

Dhillon says that it is sad that such ignorance persists. He said, “To veil the hateful pins with the thought that they somehow represent the true history of our country is irresponsible.”

“They were symbols of hate in 1990 and they remain that today.”

It is an insult to the members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who wear turbans to say that the argument over their ability to wear them was a "fun time." He added that someone who held such an attitude was someone who had not fully understood what it means to be Canadian.

*Based on an article by Douglas Quan, published in The Star on 9th May 2021