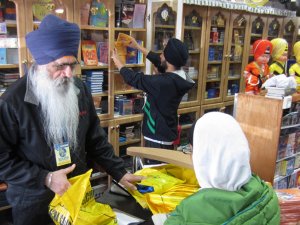

THE SIKH HERITAGE: Beyond Borders. 415 Pages: Author: Dalvir S. Pannu 1019. Thomson Press, India.

Pannu’s monumental book is a work about faith and the crisis the followers of the faith suffer with the loss of access to the location of their origins. ~ source

Book Review: by I.J. Singh, New York

I have, over the years penned a few books and reviewed a few more. Within minutes of getting this book by Dr. Pannu, it was obvious that this heavy-duty tome was not to be lightly consigned to a hidden corner of a bookshelf. It deserves to be read again and yet again. My effort is somewhat of a book review.

It is the land that sustains

When the author, Dalvir Singh Pannu, sent me a copy of his pride and joy, I saw it as a chore to write about a land and its people. Now having enjoyed my romp through it, I see this work as a delight.

In time, people develop unique relationships with their swath of land. They settle as tribes with a unique connection to the land. This transcends owner-ship and becomes unquestionably personally magical.

Punjab has a captivating narrative. Who are the Punjabis and where did they come from? By its critical location Punjab brings us unique and rich history that resounds with the human journey. Often history seems fixed beyond all doubt. But a little honest effort bares elements that range far from certainty.

Punjab & Punjabis

Was the past always so rosy? So, we think when we step back into the past, where childhood seemed innocent, and homes and neighborhoods idyllic. Many modern commentators on Sikhism seem to fall into a similar time warp. Whenever we revisit the past, we encounter a magical mix of truth and fiction that is almost impossible to parse completely while the journey holds the mind spellbound.

When the Gurus walked the Earth, Sikhs seemed idealistic and unmatched in the pristine purity of their faith. The message of the Gurus attracted both Hindus and Muslims - members of the two dominant religions of the day in India.

During the immediate Guru and post-Guru periods, gurdwaras were teeming with both Muslims and Hindus. And yet, much tension, at times violent, also ran rampant between the three faiths. Our relations with non-Sikhs were largely non-controversial and non-confrontational. I say this despite the many armed conflicts in history with either Hindu or Muslim foes, when many of our allies also came from the same two religions.

At the end of his mortal life, Guru Nanak’s Hindu followers wanted to cremate him the Hindu way; Muslims honored him by wanting to bury him by Islamic rites. Each community erected a monument to Guru Nanak’s memory; both markers still exist in a unique tribute to Guru Nanak, founder of the Sikh faith. Having come mostly from Hindu ancestry, Sikhs remained culturally close to Hindus. Hindu-Sikh mixed marriages were not uncommon; nor were they labeled as interfaith unions; they did not endure two different religious rites and wedding vows.

In gurdwaras, distinction was not often made between a Sikh and a non-Sikh. It was common to see Muslim or Hindu musicians, donning caps or scarves, performing kirtan (singing of Sikh liturgy) or conducting a reading from the Guru Granth. Non-Sikh artists showcased their talents in gurduaras and payed their homage to the Gurus who were unexcelled patrons of classical Indian musicology.

Gurduara Functions were usually open to our non-Sikh brethren. Communities of people, such as Sindhis, were Sikhs to all intents and purposes, except that they rarely took on the baana (external visage) of the Khalsa, with unshorn hair. Everyone was welcome in the gurdwara, regardless of religious label.

Less than forty years ago, the eminent thinker Kapur Singh opined that the religion of Punjab, even of Punjabi Hindus, was Sikhism, whereas Hinduism was merely the culture of all Punjabis, no matter what religion they professed. Unmistakably, religions of the world, when in Punjab, were touched by the practice of Sikhi, and by the universality of Guru Granth. This was true for both Hinduism and Islam, perhaps even Christianity to a lesser extent.

Now, things have changed at an alarming pace. Look at any gurdwara in India or abroad and hardly any Punjabi Hindus come by; certainly, raagis and lecturers who are non-Sikh or non-recognizable Sikhs are now rarer than hen's teeth.

Perhaps reality was never quite as Edenic as I describe here; nor was it ever as hellish as it seems to have become. Why and how things changed? That's my mandate to briefly explore.

First a set of givens.

The message of the Sikh path and of Guru Granth is entirely inclusive without a line in it to justify expelling those who come to it. A starting definition derived from the Guru Granth might label a Sikh as anyone who calls himself or herself a Sikh. (Simplistic but a useful device at times.) All those who call themselves Sikh, then, are on the same path, though not always at the same place on the path.

How did Punjab become what it is today? I was a preteen when India split into two nations: India and Pakistan. History speaks of large migration of Caucasoids from Asia Minor in two directions – towards Europe and towards India through its North-Western range (Khyber Pass). This pass opens into North-Western Punjab and many invaders, travelers and traders hurtled across it into Punjab. The resulting genetic hybridization enriched Punjab, its culture, cuisine, language enriching its gene pool. Punjabis remain a progressive people – conquistadores with a distinct flavor and heritage. A rich heritage created a colorful past; Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh way of life in the early 16th century which came to dominate.

History tells us how we become what we are. Treasure the heritage. This is the goal of the painstaking research that Dr. Dalvir Pannu has recorded. Where it will take us time will tell.

Many a rich mine stands unearthed. Dr Pannu carefully examines monuments, community centers, mines, monuments -- a rich mother lode of 363 sites. New faces and new images will reveal new truths about Sikhs of that time and of today. To reexamine old truths anew does not mean to repolish anew but to look with a different eye, not to recreate the hoary past but to reinterpret the past. The past needs to be renovated not replaced. Every new generation needs to discover such newness in history.

Let's come at it a tad tangentially.

Christianity now has over 250 denominations and sects; many do not recognize the others as Christians. Some disallow their members to attend services in the other's church or marry someone from another denomination. Many variations dot Christian practices worldwide. Yet, they all derive their inspiration from the life and teachings of Jesus.

Sikhism is now about 550 years old. The heritage continues to change and we should not expect less even if we regret it. With time, some divisive interpretations of the message are inevitable in living traditions. All living things and organizations, even those that originate from the same starting point, show change, some for the better, others perhaps not.

During the first 400 years of Christian history, there were no clear-cut distinctions between Jewish practices and their Christian adaptations. (Some scholars extend the period of mixed Judeo-Christian practices to the eighth century.) Another strong movement, "Jews for Jesus" existed that celebrated Jesus as the Messiah that the Jews were waiting for. The movement, now considerably attenuated, still exists.

From that time on, Jewish and Christian thought have diverged considerably and now it would be asinine for one to claim that Christians are Jews simply because Jesus was one, or that Jesus is the Messiah that the Jews have been waiting for.

Similarly, one may argue for overlapping of Hindu and Sikh practices in the early years, but over the last century, largely due to the rise of the Singh Sabha movement as well as a better educated clergy and laity, it would be very shortsighted not to recognize that the two religions show a growing divergence in theology and its interpretation, and consequently in their practices.

The process of erecting fences between Sikhs and their neighbors has been further hastened by domestic Indian, as well as international, political realities.

When India became independent in 1947, Punjab, the Sikh homeland, was essentially partitioned into two nations. Sikhs bore the brunt of the economic loss, as well as that in human lives. The great majority of Sindhis, who straddled the divide between Hinduism and Sikhism, were lost to Sikhs. For the first time in a millennium, Hindus - the large majority in a free India - felt the power that comes with freedom. Each community became engrossed in its own realities; fences between them were a natural corollary.

The successive governments of free India learned to cater, even pander, to the majority that was Hindu to capture their vote banks. (Remember that politics value head-counts.) In this power ploy, minorities became further marginalized. This is not the time or place for an exhaustive exploration of these divisive political realities, but the events of 1984, when the Sikh minority was targeted, and those of Godhra, and others like it, that were aimed at Muslims and Christians, were a predictable result. (The killings at Godhra by Hindu mobs in 2002, also appear to have been organized and abetted by the government in power at that time and claimed several thousand Muslim lives.)

How would minorities react when they see themselves so besieged? Obviously, they circle the wagons to protect themselves. The result: an inevitable alienation from others, though it is contrary to the message of Guru Granth.

In the diaspora, Sikhs remain an even smaller minority than in India, even though there are almost a million in North America alone. Our turban and unshorn hair attract the most attention. More so in the past, but even now, we are sometimes challenged by prospective employers on our bearded and turbaned visage. Sometimes, the attention is grossly negative, particular post-9/11.

Sikhs appear divided between those who continue to follow the dictates of the faith and those who have chosen to abandon them. Ideally, this should not become a divisive matter in the Sikh community. Remember that the gurduara remains open to all Sikhs, it historically remains equally open to all, even to non-Sikhs.

The problem arises when the spokesmen for the community, who have abandoned the markers of their faith, are unable or unwilling to defend the practices of the faith when they represent us to the outside world. And, that, then, impacts the whole community.

If visible markers of leadership are denied to these people, they are not given equally visible place in community leadership and they see it as discrimination. The other side of the argument is that a minority, finding its practices under siege, wants to put on the stage, in the gurdwara and the world, only those who at least look like role models.

I would tell my turbaned brothers, and also those on the other side of the divide, who are not so attired, not to be so thin-skinned. Let's see if we can work through this.

How to resolve this is the question. Either all those who wish to potentially lead us from a gurdwara agree to defend the teachings of what is our code of conduct (Sikh Rehat Maryada), even if they personally fall short of it, or the conflict will continue to escalate.

If they can openly support our historic teachings and religious requirements in spite of any personal failings of their own, then there should be no reason for conflict between those who are keshadhari (maintaining unshorn hair), and those who are not.

These kind of issues lie at the heart of heritage and what it means, particularly when such issues lie beyond borders. In my opinion this critical area lies untouched today. And without dissection of such questions our consideration of heritage is limited to repetition of practices without meaningful application.

If such a modus operandi seems impossible, then what?

A not so attractive, but perhaps inevitable alternative, again comes to me from the Jews. They are divided largely into Conservative, Orthodox and Reform congregations that have fundamental differences in what a Jewish lifestyle is. Hence, the respective synagogues of the three are separate, yet when a question arises that is important to the whole Jewish nation, most of them speak with one voice.

This does not mean that even on matters of substance they do not differ; for example, there exist Jews that do not approve of a Zionist state of Israel.

Much as we dislike the idea of sects within Sikhism, they do exist; just look at Namdharis, Radhaswamis and followers of Harbhajan Singh Yogi, for example. All religions acquire some sects with time.

I can see, with time our diaspora Sikhs fissuring along a line that separates those that are keshadhari, whether amritdhari or not, and those that are not recognizable Sikhs, whether they are sehajdhari or apostate. Or perhaps, it would be a tripartite segmentation: amritdharis, keshadharis but not amritdharis, or unrecognizable Sikhs, whatever their reasons for it.

Perhaps, then, we will also be able to work with each other in matters of discrimination in the work place, and even have some gurdwaras that are happily intermixed.

Important issues of faith and loyalty tug on us. History sometimes touches the complexities of the human mind, but all the head scratching doesn’t always clear the hurdles that humans face.

The umbrella or tent of Sikhism is large and capacious enough to accommodate all those who are on the same path, no matter where on it they are at a given time. And this is how I see the message of Guru Granth and Sikh historical tradition.

11/28/2020