"Engendering the Female Voice in Sikh Devotional Music: Locating Equality in Pedagogy and Praxis"

ABSTRACT

The Sikh Gurus promoted gender equality, but still women’s voices are being silenced from playing Gurbānī Kīrtan inside the Golden Temple. The reasons for their exclusion center around the sexualization of the female body, purity and pollution, appeals to tradition, and questions of musical proficiency. Today, Sikhs in India and the diaspora ask that the Sikh philosophy of equality be fully enacted in pedagogy and praxis. Through ethnographic investigation, historical analysis and critical inquiry, this paper addresses the importance of liberating the Sikh self and psyche from institutional systems of oppression to reclaim Sikh sovereignty, equality and the female voice.

Introduction

Liberation is a praxis: the action and reflection of men and women upon their world in order to transform it. (Paulo Friere 2005 )

Equality in diversity, individual sovereignty, selfless service, and life-long learning are foundational Sikh philosophies. However, today women in India are not admitted to the all-male institutions (vidyālās) that train professional Sikh Kīrtan musicians (rāgīs) and are therefore excluded from playing Gurbānī Kīrtan (Sikh devotional music)11. While it may be insufficient to define Gurbani Kīrtan with the term ‘devotional music,’ it serves an explanatory purpose when speaking to a general audience. It has been described as ‘liturgical music’ which, though descriptive in its function, carries Catholic connotations. Bhai Baldeep Singh defines it as singing the utterances of the enlightened ones that dyes the body in the loving praises of the divine. In line with this perspective, Dr. Francesca Cassio in her paper ‘The Sonic Pilgrimage: Exploring Gurbani Kīrtan as a Vehicle of the Spiritual Journey’ presented in this volume clearly demonstrates that its dhrupad and partaal musical structures, as well as its purpose and effect are significantly different from the devotional song-forms of Bhakti Kīrtan. However, Bob van der Linden in his article presented in this same volume ‘Songs to the Jinas and of the Gurus: Historical Comparisons between Jain and Sikh Devotional Music’ understands Sikh Kīrtanand Jain Bhajan to both be part of the bhakti devotional movement due to their similar forms and functions such as the pada verses, use of vernacular language, links with folk music genres and aim for spiritual progression. Thus Sikh Kīrtan or Gurbani Kīrtan can be understood as a musical form that is not merely devotional but spiritually transformational. I, therefore, offer that it is not merely musically adept or aesthetic but is a spiritual-aesthetic musical form (Khalsa 2012) in the inner sanctum of the Golden Temple (aka Darbar Sahib or Harimandir Sahib). However, through the democratization of the musical sphere of postcolonial India, there is now a growing trend towards women learning Gurbānī Kīrtan in other venues, including institutes of higher education (ex. Gurmat Sangīt Department at Punjabi University, Patiala), as part-time students at Sikh music institutes (ex. Jawaddi Taksal, Ludhiana), or from a variety of teachers who lead musical workshops in India, abroad, and online. Nevertheless, women’s primary professional recourse within India is to become music teachers and concert performers. They are not able to become professional Gurbānī Kīrtan musicians or rāgīs stationed at historical Gurdwaras, invited to play at the Golden temple, or tour Sikh sangats in India and the diaspora. Due to the changing socio-political climate, Sikh women and men both in India and the diaspora are now questioning culturally received gender norms and asking for a more egalitarian re-visioning within Sikh pedagogy and praxis to mirror the equality professed by the Sikh Gurus.

The work of this paper is to bring the shadow to light, to acknowledge the oppressive structures that prohibit women from performing sevā to their Guru at the Golden Temple, the Sikh spiritual throne, and to witness the Sikh spirit that continues to fight for equality, sovereignty, and respect. It will do so through ethnographic accounts by male and female Sikh musicians, scholars, teachers, memory bearers, and religious leaders taken from interviews conducted in India and the diaspora, debates hosted by Indian and diasporic media outlets, and a panel I organized at the 2015 Parliament of World’s Religions.

Hearing Sikh voices is crucial to understanding the many reasons why women are not given equal opportunities to participate in all Sikh sevās and roles of Sikh leadership. These reasons include appeals to tradition (maryādā) to preserve the status quo as well as the need to control, protect and hide women’s bodies from the male gaze that views them at the same time as sexual, pure, and polluted. Women voicing the disconnect between the Guru’s rahit (as found in Gurbani) that promotes equality in lived practice and the current maryādā, have been silenced by patriarchal authorities acting as gatekeepers to the Guru’s court. This bifurcation of philosophy and praxis is the crux of the issue. It has created an inauthentic relationship to a false unity of a divided self that Paulo Friere states, in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, needs to be acknowledged and recognized as the imprisonment within a system of oppression that offers a future without hope (174). The disjuncture of the Sikh psyche and praxis due to tyranny, colonization, and the Indian state must be acknowledged in order to liberate the Sikh body and return it to a wholeness. For healing to take place, all (regardless of gender, caste, creed, or sexual orientation) must be treated as equals in praxis, not just in philosophy. This means bringing the shadow to light, transforming the male-dominated psyche through the feminine poetic consciousness of Gurbānī, and healing the relationship between the male and female, the public and private, the miri (temporal) and piri (spiritual).

Gender equality in Sikh philosophy

In the late 15th century, Guru Nanak, the first Sikh Guru, delivered a revolutionary message of equality across gender, caste, and creed through song, in the language of the people. Guru Nanak himself clearly expresses the respect that should be accorded women in the shabd ‘Bandh Jameai’ sung every morning in the Asā dī Vār by professional Sikh male rāgīs in the Golden Temple.

From woman, man is born; within woman, man is conceived; to woman he is engaged and married. Woman becomes his friend; through woman, the future generations come. When his woman dies, he seeks another woman; to woman he is bound. So why call her bad? From her, kings are born. From woman, woman is born; without woman, there would be no one at all. O Nanak, only the True Lord is without a woman. That mouth which praises the Lord continually is blessed and beautiful. O Nanak, those faces shall be radiant in the Court of the True Lord (GGS 473).

The consecutive Sikh Gurus continued to transmit the message of equality through a musico-poetic mode. 22. These hymns were then compiled and enshrined into the Sikh scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib (GGS), to which the Tenth Guru transmitted the authority of the Guruship. Today the Guru Granth Sahib contains the hymns of Sikh Gurus and other saint-poets and is revered as the everlasting Guru of the Sikh community. Sikh musicians sing these hymns, or bānī, evoking the Guru within Sikh services. Within the Guru Granth Sahib (982) the fourth Guru, Ram Das proclaims:

Baṇī gurū gurū hai baṇī vicẖ baṇī amriṯ sāre.

The Word, the bānī, is Guru, and Guru is the bānī. Within the bānī, the Ambrosial Nectar is contained.

Gur baṇī kahai sevāk jan mānai parṯakẖ gurū nisṯāre. ||5||

If His humble servant believes and acts according to the Words of the Guru's bānī, then the Guru, in person, emancipates him. ||5||

In her book, The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent (1993 Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur. 1993. The Feminine Principle in the Sikh Vision of the Transcendent. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press.[Crossref], [Google Scholar]), Dr. Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh reminds us that ‘bānī,’ the term for the hymns or divine word, is feminine in gender (9). Thus, when Sikh practitioners recite, sing, and meditate on these hymns in their daily life, they are embodying the Guru-as-bānī(Gur-bānī), a feminine divine consciousness in thought, speech, and action. In addition, the male Guru, Sikh and bhagat (poet-saint) authors of Gurbānī themselves take on a feminine subjectivity through their poetic voice, describing themselves as brides longing for union with the Divine, their beloved Groom. Singh states that while ‘the communicators were all males; their revelation, the feminine principle, takes equal rank with them’ (44). Here she indicates the authority given to the feminine voice and poetic language which is understood by psychoanalytic scholars as being a form of language that is ‘non-domineering,’ and has the potential to castrate the phallocentrism of the male ego (Ruti 2006). Feminist theorist Robin Truth Goodman acknowledges the ability of language to uproot inequality ‘along with its seemingly entrenched meanings assigned to seemingly entrenched identities’ (Goodman 2010).

Taking Goodman’s cue, we can identify the entrenched identity of rāgīs as a male-gendered profession due to their often being referred to as ‘rāgī Singh’ (Cassio 2014). Nevertheless, we can question this entrenchment when examining the experiential relationship between the public male ‘rāgī’ enunciators and the devotional ‘private’ feminine enunciation (bānī). Jewish feminist scholars warn that just because the discursive language may promote the feminine principle, it does not necessarily mean that it translates into lived experience. Boyarin in his work ‘Feminization and Its Discontents: Torah Study as a System for the Domination of Women’ points out that the ‘male self-refashioning has consequences for women’ by creating a ‘kinder, gentler patriarchy’ that does not make it any more egalitarian (Boyarin 157).33. In the case of Sikh devotional practice, when the egalitarian feminine principle is engendered through singing or reciting the bānī, but not embodied and enacted in praxis, then any reference to Gurbānī’s egalitarian ideals becomes caught in a patriarchal discursive system. The discourse becomes ‘detrimental to women’s agency but not their physical welfare’ (Levitt 235). It causes a ‘psychic pain due to the constant insult and denial of value and autonomy that the system produced and enforced’ (Boyarin 156). Sikh women being excluded from participating in certain sevās and leadership roles demonstrates a ‘structural, ritual expression of an inferiority of women “in rituals or etiquette regulating public contact between strata”’ (Scott 1992).44. Scott, J.C. Domination“You may not tell the boys” xi. Quoted by Boyarin (154). In other words, when Sikh ritual roles are constructed within patriarchal logics, it secures male dominance and controls women by separating them from the public and making them the object of discourse. To support female discursive agency in ritual praxis, Nikky Singh’s work The Feminine Principle focuses on female interpretations and translations of the bānī, which have the ability to address the very ways in which the Divine One is translated, as a male God (117). Just as the feminine principle is valued within Sikh philosophy, Nikky Singh proclaims that within lived praxis ‘women must have equal role in public worship’ (118). Within the current patriarchal system, ‘women are tacitly discouraged from conducting public ceremonies’ and are instead relegated to the private roles of cleaning and cooking where they ‘rarely lead services’ (118).

While Sikhs readily claim the foundational principles of equality, respect and dignity to all by citing scriptural and historical examples, this is often where the conversation stops, acting as a barrier to deeper critiques. Due to this lacuna, the work of this paper is an effort to bridge the gap between the Sikh philosophy of equality and the barriers to equality found in lived praxis.

Discordant discourse: (Dis)empowered philosophy, pedagogy and praxis

To affirm that men and women are persons and as persons should be free, and yet to do nothing tangible to make this affirmation a reality, is a farce (Friere 50).

In 2006, the World Economic Forum (WEF) began tracking worldwide gender disparities through the Global Gender Gap Report (GGGR). Each year it has ranked India as one of the lowest nations in gender equality and educational empowerment for women.55. In the 2018 Global Gender Gap Report (GGGR) by the World Economic Forum (WEF), India was ranked 108 out of 149 countries. While India’s gap is improving with regards to educational attainment for women, overall there remains a 33% gap still to be bridged when taking into account the other key indexes including Health and Survival, Political Empowerment, Economic Participation and Opportunity. (25) This gender-based disparity is not surprising when we look at Indian history of female exclusion, particularly within musical education. Sikh scholarship is also beginning to address this gender gap within Sikh music which denies women access to vidyālā educational institutions that train Sikhs in ritual leadership roles.

In India, Sikh women do not commonly hold religious leadership roles. They cannot become granthīs (custodians of the Guru Granth Sahib) or conduct the amrit (baptismal) ceremony as one of the five beloved panj pīyāre (Khalsa representatives). At the Golden Temple, women are excluded from performing many sevās in the inner sanctum including Gurbānī Kīrtan, ishnān (washing the marble floors) and carrying the Guru during sukhasan (resting) and prakash(awakening). However, women in the Sikh diaspora have more access to perform all the sevās in Gurdwara service and leadership. In the westernized 3HO-Sikh Dharma community,66. women serve as professional touring Sikh kīrtan musicians, as ministers who officiate Anand Karaj wedding ceremonies, serve as the panj pyari in the Amrit baptismal ceremonies, fulfill all ritual and ceremonial roles within the Gurdwara, and serve as the heads of Gurdwara boards and Sikh-run businesses.

Sikh women as part of the panj pīyāre Baisakhi 2019. Los Angeles Convention Center.

(Photo by Siri Dyal Kaur.)

There are those who critique these diasporic practices and calls to egalitarianism as products of western feminism, class and privilege arguing that it is ‘merely the selfish needs of “outsiders,” namely, “Westernized” Sikh women’ because ‘many women and men continued to insist that specific gender roles in Sikhism had never been an issue for Indian Sikh women’ (Jakobsh 600).77. Doris Jakobsh refers here to the work of Jhutti-Johal (2010) Jakobsh relates these controversies and the variety of perspectives surrounding women’s roles to egalitarianism, honor, and shame which blur the public-private dichotomy because they relate both to controlling female sexuality (private) and feminine behavior (public) (Jakobsh 601).

Sikhism, being a householder religion, values women for their roles in the private sphere in service to their family and communities. This view becomes problematic when traditional gender roles are imposed as obligatory duties and do not provide women the ability to choose otherwise. ‘Women’s duties’ have kept women bound to the private sphere and barred from the male-dominated public sphere.88. For example, as scholar Natasha Behl has pointed out ‘by emphasizing women’s seva as mothers [it] questions Sikh women’s participation and belonging outside the home … because women’s greatest seva is equated with the home, marriage, and motherhood’ (2014). It creates what Behl refers to as ‘exclusionary inclusion’ that shrouds the dichotomy between Sikh ideals and lived practice. The teachings of the Sikh Gurus have attempted to uplift women’s agency and sovereignty from the cultural-lived soil that has subjected them primarily to the domestic sphere. At the same time, the Sikh value placed on selfless service or sevā enables us to understand its value and appreciate current requests for women to have equal opportunities to perform all sevā at Darbar Sahib.

Sikh diasporic feminists are now working to address the disconnect between egalitarian values and lived praxis.99. To uphold the Sikh values of equality, sevā and sovereignty they are addressing those systems of oppression and domination that have subjugated and marginalized women’s bodies and voices (Khalsa 2017).1010. In 2017 Anneeth Kaur Hundle, Tavleen Kaur and myself published ‘Provocation’ pieces in Sikh Formations(13:4) on “Sikh diasporic feminisms” as an intervention. My piece “The Ecology of Sikh Diasporic Feminisms: Interconnected Ethics of Seva and Sovereignty” stated ‘our goal within diasporic Sikh feminisms is to promote a Sikh notion of individual sovereignty that is not bound and buried under oppressive systems of power but is free to grow within a mutually nourishing ecosystem.’ It addressed how many ‘question the usage of the term ‘feminisms’ to identify whether it is necessary, useful, or misrepresentative because of the Anglo-Christian-Western centric notions that have long dominated the discourse on political claims to gender equality. Rather than re-institutionalizing another ‘ism’ that imposes the same dualistic notions denounced by the Sikh Gurus - the dichotomies between inner and outer, purity and pollution, high and low, man and divine - we instead look for a term that encapsulates the equality and non-suppression of one ideology over another. However, through the use of the term ‘Sikh diasporic feminisms’ we appreciate the plurality of identity inherent in the term which can expansively encompass the genderless or fully engendered nature of Sikhī whose notion of Ik Ongkar transgresses all manmade linguistic, social, and religious boundaries. As diasporic Sikhs ourselves, we use the term ‘diasporic’ to indicate our engagement with the present, ever evolving, lived context of global Sikhī. When speaking of the ‘diaspora’ we do not aim to exclude Sikhs living within India, but rather offer the term as a movement beyond geographic and linguistic boundaries. As an Anglo-American Sikh born into Sikhī, I also use this term expansively to include our global Sikh community as a spiritual-religious diaspora beyond ethnic, social, national, linguistic or cultural confines.’ (246) Khalsa (2017 This work is not meant to exclude nor divide men and women living within India and the diaspora, but instead to highlight the breadth of the Guru’s vision for Sikh sovereignty and equality that transgresses geographic, cultural, and linguistic boundaries. The Sikh diasporic feminist intervention aims to bring to light the divided nature of Sikh subjectivity and the illusion of an authentic identity. It asserts that liberating the Sikh self, psyche, and praxis begins in acknowledging its imprisonment (Friere 151).

The divided self: experiencing (Dis)empowerment in musical education

Part of the oppressed I is located in the reality to which it ‘adheres’; part is located outside the self, in the mysterious forces which are regarded as responsible for a reality about which nothing can be done. The individual is divided between an identical past and present, and a future without hope. (Friere 173)

I acknowledge my own privileges as an Anglo-American Sikh woman born into the 3HO-Sikh Dharma community, which gives me a different cultural vantage point to enter into this discussion. I grew up with the teachings of Siri Singh Sahib Bhai Sahib Harbhajan Singh Khalsa Yogi Ji (Yogi Bhajan) who promoted gender equality as a foundational Sikh concept. He enacted the egalitarian Sikh philosophy in praxis by appointing female leadership in Sikh religious and business spaces. He uplifted the power of the female, calling upon American women to no longer be referred to as adolescent ‘chicks’ but hailed as dignified ‘eagles’. Rather than teaching a form of feminism that requested women to be like men, he instead grounded his feminist teachings in Sikh and yogic thought which upheld the feminine as the creative Shakti power whose ‘caliber, consciousness and self is sixteen-times stronger than all the men’ (Yogi Bhajan lecture June 28, 1994Yogiji, SSS Harbhajan Singh Khalsa. 1994. “The World Starts with Woman.” Yogi Bhajan Lecture June 28. Accessed April 15, 2019.[Google Scholar]).1111 View all notes He created Khalsa Women’s Training Camps (KWTC) for women to experience their own power first hand through yoga, meditation, martial arts, and weapons training. During these camps, men stayed home to care for the household, giving them an experience of the value of women’s ‘unpaid labor.’ His teachings uplifted the various manifestations of the mother in the biological, spiritual, and earthly realms, demanding she no longer be mistreated or exploited.

I ask every man who would seek peace to realize that peace doesn’t come by protests and rallies. Peace comes by peaceful actions, and so long as those born of the mother will not learn to respect the woman, there shall not be any peace on this planet. The day the woman will not be exploited on this planet, there shall be peace on this Earth (Yogi Bhajan lecture May 9, 1971

Yogiji, SSS Harbhajan Singh Khalsa. 1971. “Shout it from the Mountaintops.” Yogi Bhajan Lecture May 9. Accessed April 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]).1212.

While Yogi Bhajan uplifted women’s biology, spirituality, and role within the household, it is important to not misinterpret their value in a way that would restrict them to predetermined roles.

The cultural implications of Sikh women’s roles within the private and public spheres, and the values accorded these roles, are continually being negotiated. Bhai Baldeep Singh, thirteenth generation exponent of the Sikh kīrtan tradition (Gurbānī Sangīt paramparā) is clear to acknowledge that women have played important historical roles as memory bearers and teachers who preserve and orally transmit Sikh knowledge, histories, and narratives.

I am reminded of, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia [1718–1783], he lost his father early, was trained by his mother. He became a favorite of Mata Sundari [Guru Gobind Singh’s wife] for what? For doing kīrtan, for playing the saranda. He was taught by his mother … There is another name in history who is noted as the greatest military journal in human kind, Hari Singh Nalwa [1791–1837]. He lost his father early in battle, he was taught by his mother. His mother oversaw his study of wrestling, of martial arts, of sword fighting, and was an exceptional kīrtanīa who played the saranda as well. So historically if we see the role of women, they were the memory bearers, the memory keepers.1313.

Bhai Baldeep Singh addresses the historical necessity to protect women’s bodies during times of socio-political upheaval: ‘If you go back as I was mentioning until late 19th century, if any woman, it was about protecting women folk. There were invaders invading Punjab, there were feudal lords, if any beautiful woman, was virtuous, was seen performing, there was political pressure, the family would be given privileges and the woman would be taken away as part of the harem. So the question to be asked is how is it that they could teach Hari Singh Nalwa, they could teach Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, but were they performing or not? The reason is, they were not performing, because they would get spotted. And they would get taken away. So within the Sikh fold for centuries knowledge was disseminated without discrimination. They were at that time, men out had to fight, etc etc. But the finer things in life, be it aesthetical attendance to scriptures or learning of music or art, they were taught without discrimination.’ This quote enables us to see that while protecting female bodies has served a purpose, the feminist work now is to reorient the male gaze away from objectifying, controlling, and causing violence to the female body, enabling women greater public freedoms.View all notes (Bhai Baldeep Singh, PWR, 2015

Khalsa, Nirinjan K., Bhai Baldeep Singh, Francesca Cassio, Bhai Kultar Singh, HarjotKaur, Sada Sat Simran Singh Khalsa, and Nirvair Kaur Khalsa. 2015. “Sikh Devotional Music: Locating Gender Equality.” Parliament of World’s Religions, Salt Lake City, Utah, October 19. [Google Scholar])

These historical examples allow us to recognize the value of women as memory bearers who preserve Sikh knowledge and pedagogy, while at the same time acknowledge the barriers that have restricted their own public praxis. Even though women have not historically served public roles as professional kīrtanīe, it is important to note that the precolonial paramparā pedagogy has historically been open to them.

In 2001, after receiving my bachelor’s degree, I was given the opportunity to learn the oldest surviving percussion tradition of Punjab, the Amritsari-Kapurthala bāj on the jori-pakhāwaj from its pagrī-nashīn (head) Bhai Baldeep Singh. After dedicating myself to this study, I soon realized, however, that no matter how much I practiced, within the current system of Sikh religious governance, I would not be able to play in the Golden Temple, heralded as a great sevā and honor for a Sikh musician.1414. This realization of the hypocrisy between an egalitarian philosophy and a cultural system of oppression within Sikh cultural praxis, made me experience within my own consciousness, a disconnected subjectivity which Paulo Friere identifies as ‘the divided self’ subject to a ‘future without hope.’ (173)

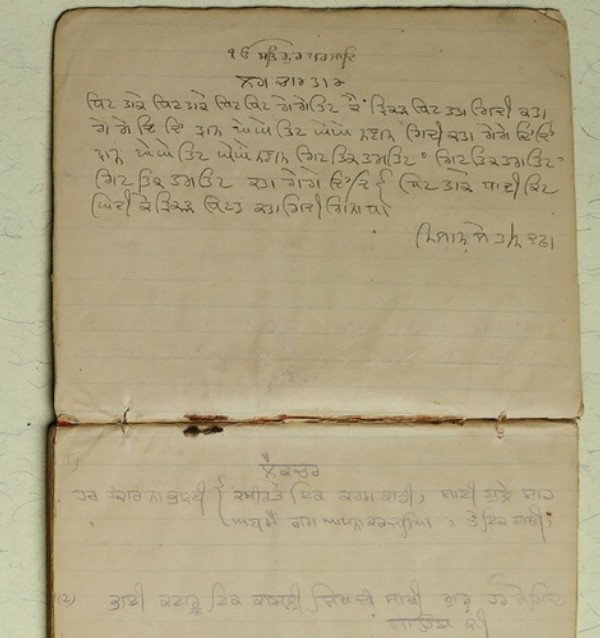

Nevertheless, after years of dedicating myself to the traditional pedagogy of the Gurbanī Sangīt paramparā, Bhai Baldeep Singh offered me hope by honoring me as the first female exponent of the Amritsari-Kapurthala bāj. He ceremoniously passed on to me the old diaries of his teachers which contain treasures of the Sikh percussive legacy, including heritage rhythmic compositions that had been passed down for centuries since the time of Guru Arjan. He recounts:

We are very fortunate beings. Bhai Arjan Singh Tarangar passed on to me his percussion gifts, the four-hundred-year-old system, the Amritsaari-Kapurthala baaj. It is my elder grand uncle, Bhai Gurucharan Singh, who had the diaries from when my ninety-year-old master Bhai Arjan Singh taught him. These diaries are in my possession, the originals. It is with these that I passed on the tradition to Nirinjan Kaur, the first woman exponent of the Amritsari-Kapurthala bāj. It is important to know where the lineage comes from. It is important to ask if we are merely interpreting music or if we are knowledgeable recipients of the tradition.1515.

Diaries passed down to me by Bhai Baldeep Singh, from Bhai Gurcharan Singh as taught to him by Bhai Arjan Singh Tarangar (1900–1995). (Photo courtesy Bhai Baldeep Singh.)

I understood the responsibility as a recipient of the near-extinct drumming tradition to dedicate myself further to its studies. I went on to graduate school at the University of Michigan in 2007 to contribute to the scholarship of Gurbānī Kīrtan. While engaging in extensive ethnographic research throughout the Punjab, interviewing extant memory-bearers, I became interested in the socio-historical context for the tradition’s change over time and significant loss of its musical memory, all the while hoping to find answers to why there has been a dearth of prominent female musicians.1616.

Growing up, it was rare to see women even playing the tabla. I remember as young girl looking up to my friend’s mother, Ram Das Kaur, who was one of the first in our 3HO/Sikh Dharma community to play the tabla, practice gatka, and fashion a woman’s turban. She was also one of the first females who sat in the rāgī section at Darbar Sahib with Vikram Singh when he became the first person from 3HO/Sikh Dharma to sing at Darbar Sahib in 1979. Witnessing a female drummer at Gurdwara and other events was the inspiration that planted in me the seed for a lifelong pursuit of drumming in the Guru’s Court (Darbar Sahib).

Nirinjan Kaur on the jorī with Bhai Baldeep Singh (2007). (Photo by Gurusevak Singh Khalsa.)

I have continued to wonder why it is that I, an Anglo-American Sikh born into the 3HO/Sikh Dharma community – am the first female exponent of Sikh percussion.1717. When speaking of the ‘first’ females to perform certain roles within Sikhī, it must be remembered that various forms of violence have been inflicted upon Sikh bodies and spaces through socio-political turmoil, including the violence of forgetting and erasure. I acknowledge my cultural privileges that have enabled me to bypass socio-cultural mores, while at the same time, recognize the difficulties of being a female student within the guru-shishya paramparā. An ideal shishya (student) serves in the teacher’s household day and night as an apprentice, a lifestyle more culturally acceptable for young male students. Feminist scholar Carole Pateman (1988) by way of Cynthia Cockburn refers to this androcentric space as ‘fraternal territory’ which makes it ‘unthinkable that a girl could be part of apprenticeship system’ because ‘“skilled” work is work done by men’ (Boyarin 1997).1818.

My research has worked to unearth the historical and socio-cultural reasons for the lack of ‘professional’ female kīrtan musicians, allowing me to appreciate at the same time how changes to these systems have now made it possible for their inclusion at this time. Due to the historical structure of the family unit, it would have been difficult for women with children to travel around the Punjab on horseback for months on end, as was recounted to me by Bhai Avtar Singh when I questioned him on this topic. Once I became a wife and mother, I more fully recognized the difficulties of balancing home and study, no longer able to dedicate the long uninterrupted stretches of time and energy to serious riyāz. The dearth of female role models who have excelled as musicians, wives, and mothers has caused me to question my own ability to fulfill such a pivotal role as being the bearer of a tradition, that has historically been carried by Indian men. Fortunately, today socio-cultural changes and improvements to technology and transportation are now giving women greater access to education, the workforce, and reproductive choice, providing more opportunities to dedicate themselves to musical professions traditionally held by men.

From left to right Nirinjan Kaur (pakhāwāj), Nihal Singh (tabla), Nanak Nihal Singh (guitar), Harbhajan Kaur (guitar), Kirpal Singh (guitar), Gurmukh Singh (vocal), Siri Sevak (vocal), Nirvair Kaur (vocal) at the Guru Gaurav event he curated in Patna Sahib celebrating Guru Gobind Singh’s 350th birthday (Jan 2017). (Photo courtesy Anād Foundation.)

Engendering equality

As he or she breaks this ‘adhesion’ and objectifies the reality from which he or she starts to emerge, the person begins to integrate as a Subject (an I) confronting an object (reality). At this moment, sundering the false unity of the divided self, one becomes a true individual (Friere 173).

Today Sikhs in the diaspora and India are directly questioning the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) about the apparent hypocrisy between Sikh values that promotes gender equality and the Gurdwara governance that continues to bar women from performing Gurbānī Kīrtan at Darbar Sahib. In the summer of 2017 a Sikh Youth Camp hosted by Guru Gobind Singh Foundation outside of Washington, D.C. made gender equality that year’s camp theme.1919. Taken from the report on Sikhnet ‘Camp Gurmat, a week-long annual Sikh youth camp, organized by the Washington-based Guru Gobind Singh Foundation (GGSF), explored the theme of Sikh women and looked in detail at women in Sikh history. Over 120 Sikh children from ages 7–17 traveled from all over the United States and Canada to be part of this camp, which is held in a green, wooded facility in Rockville, in the suburbs of Washington, DC. Sikh youth and camp organizers in Washington raised the question of why Sikh women are not performing kīrtan at Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple), the sacrosanct of the Sikh faith … . Throughout the entire week, Sikh youth sang the theme shabad ‘So Kion Munda Aakhiye, Jit Jamey Raajaan’ written by Guru Nanak which exhorts that women be treated with respect and fairness. This shabad was discussed in detail, in addition to the philosophical aspects of Sikh theology which emphasize social and gender equality.’ (July 27, 2017) ‘Sikh Americans propose to entitle women to sing at Golden Temple’ View all notes Understanding Sikhī as both inherently feminist and genderless, Sehejneet Kaur, a counselor at Camp Gurmat, said:

Sikhism is feminist at its very core, and if you believe in the Sikh principles and Guru Nanak's values, you are inherently a feminist. However, we are afraid because of the stigma that comes with the word ‘feminist’. But being a feminist just means you believe that every being on this Earth is equal and should be treated as such, and this is what our Gurus believed. Sikhism is genderless, so why do some Sikhs think it is okay to go against what our Gurus preached and practice Sikhism with a sexist mind?

Requests for women to play Gurbānī Kīrtan inside of the Golden Temple’s sanctum references the invaluable role of Sikh women throughout history, asking that women are given the honor of doing kīrtan sevā in the Guru’s Court at Darbar Sahib.

Vikram Singh (Antion) in 1979 playing Gurbānī Kīrtan at Darbar Sahib with Ram Das Kaur

seated far right. (Photo courtesy Antion Vikram Singh.)

Since the 1970s, there have been attempts to integrate females into Sikh ritual service and leadership, mostly initiated from 3HO/Sikh Dharma and the Punjabi Sikh diaspora. In 1979 Vikram Singh became the first white Sikh American man to perform kīrtan in Darbar Sahib. 3HO Sikh women sat and sang with him. Then, in 1982, Krishna Kaur, an African-American 3HO Sikh woman sang on the roof-top Gurdwara of the Golden Temple. Vikram Singh was also there at the time and encouraged her to go and sit with the support of Baba Nihal Singh, Jathadar of the Nihung Tarna Dal. She recounts the experience:

We of the Guru Ram Das Ashram [in Los Angeles, CA] did work for changes at the Golden Temple in Amritsar, changes that would give Sikh women more equality there. In fact, I believe I was the first woman to play kīrtan there, on my harmonium, at an akand path for Yogi Bhajan in 1982. We were there [at the Golden Temple], our kīrtan group from Los Angeles, and there was the bhog, and then to complete the cycle the rāgīs should play. One of our people [Vikram Singh] nodded to me, inviting me to play; and I was aware that local practice did not sanction that but I was ready. And just as I was about to begin, I saw the Punjabi Sikh man, the leader there, get up to object, but just then a beautiful Sikh, Baba Nihal Singh, walked in the door and smiled at everyone, smiled at me as I sat to play. So I played. (Interview courtesy Dr. Karen Leonard and Ben Caldwell Forthcoming

In both instances, the support of Sikh men was crucial for providing women the space and opportunity to perform kīrtan sevā in Darbar Sahib. In addition, the presence of the acting Akal Takht Jathadar Manjit Singh allowed a group Indian and 3HO Sikh women, including Bibiji Inderjit Kaur (wife of SSS Harbhajan Singh Yogiji), to do ishnān sevā in the inner sanctum of Darbar Sahib in 1996. Men play a pivotal role in changing patriarchal structures from the inside and dismantling systems of oppression that have long barred women from the public sphere in India.

Krishna Kaur (center) learning Gurbānī Kīrtan with other 3HO Sikhs at the Golden Temple

complex in Amritsar, India. (Photo permission of Kundalini Research Institute.)

In 1996 Kaur, Surjit. 1996. “The Place of Women in Sikhism: Unequal Partners?” Sikh Review 44 (4), 35–40. [Google Scholar], Surjit Kaur wrote an article for the Sikh Review about a woman in California who had applied to be a granthi sharing that ‘she excelled her male competitors in terms of her qualifications, but was turned down because the managing committee did not feel comfortable in hiring a woman for a position which is considered the monopoly of male members.’ Her article further recounts the misogynistic reasoning for denying women such opportunity because ‘the best place for women is home and the only education they need is to qualify for a good, educated, and preferably, rich husband’ (36).

Regardless of the misogynistic perspectives and discriminatory treatment, we do see both Sikh women and men making formal requests to the SGPC religious authorities for women to have the same opportunities to serve the Guru and sangat. In 1996, a Hukamnama was issued by the SGPC to allow women to do ishnānin the inner sanctum of Darbar Sahib.2020. View all notes During this time, Sikh women from India and the West went to Darbar Sahib and successfully participated in this sevā. However, the ruling was not upheld and women attempting to do the ishnān and sukhasan-prakash sevās continue to be stopped. This caused the popular website Sikhnet 2121. Sikhnet was started by Gurumustuk Singh Khalsa, a 3HO/Sikh Dharma man who went to boarding school in India for most of his life, along with the other second generation children born into the community.View all notes in 2003 to formally launch an online petition requesting the original 1996 Hukamnama be upheld, yet to this day, Sikh women are still barred from this sevā.2222. Finally, in 2004 a woman was promoted to a prominent leadership position when Bibi Jagir Kaur became the first female president of the SGPC, the Sikh religious governing body.2323. With a women’s voice and presence now in a seat of authority she was able to formally propose a resolution to allow women to perform Gurbānī Kīrtan in Darbar Sahib. However, there was not sufficient support from the male members to pass a resolution.2424.

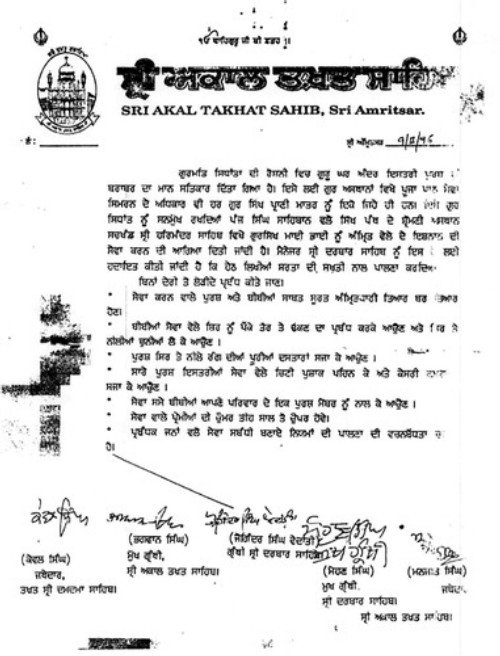

Sri Akal Takhat Sahib 1996 Hukamnama allowing women to do ishnān sevā

inside the Golden Temple. (Courtesy Sikhnet.com)

Bibi Jagir Kaur paved the way for more female leadership within the SGPC, including Kiranjot Kaur who served twice as general secretary. She also worked to give women the right to perform kīrtan and all sevās at Darbar Sahib. In 2017 she wrote an op-ed piece in Times of India ‘Why debate kīrtan by Sikh women in Darbar Sahib? It's our indisputable right' proclaiming:

Gender equality is a big issue in the twenty-first century. Women are demanding ‘rights’ which are ‘equal’ to men. Religion, which has traditionally been dominated by men, is also not immune to the new-found awareness among women. For long, women have been subjugated because of ‘God's word’ and now they are no longer buying this story! In Sikh religion, the assertion for equality is finding voice on the issue of Sikh women not being allowed to perform kīrtan in Harmandar Sahib. Live telecast of kīrtanworldwide calls attention to lack of women participation.

While Sikh women are being given more access to fulfill leadership roles and gain more public authority within Sikhī, the male gatekeepers remain unwilling to open their doors to true equality, and when they do it is often due to tokenism. To make lasting change, it becomes the onus of men in roles of religious leadership and power to change the patriarchal system from the inside by fearlessly demonstrating their support of enacting the Sikh ideals of equality in praxis.

Parliament of world Religions: Locating gender equality

Thematic investigation thus becomes a common striving towards awareness of reality and towards self-awareness, which makes this investigation a starting point for the educational process or for cultural action of a liberating character (Friere 107).

In an effort to bring greater equality to Sikh praxis through the support of prominent male voices, I organized a panel at the Parliament of World’s Religions (PWR) in Salt Lake City, Utah entitled ‘Sikh Devotional Music: Locating Gender Equality’ on October 19, 2015. The goal was to create a dialogue with Punjabi and non-Punjabi Sikh devotional musicians and scholars, men and women, and explore strategies for bridging the gender gap in Sikh musical practice. The panel included eleventh and thirteenth generation exponents of Gurbānī Kīrtan Bhai Kultar Singh and Bhai Baldeep Singh; Chair of Sikh Musicology at Hofstra University, Francesca Cassio; Hazoori Rāgī Sadasat Simran Singh Khalsa of Chardi Kala Jatha; Sikh minister and musician Dr. Harjot Kaur Singh; along with myself, and chaired by taus musician Nirvair Kaur Khalsa.2626.

From left to right, Bhai Baldeep Singh, Nirinjan Kaur, Dr. Harjot Kaur, Bhai Kultar Singh,

Sada Sat Simran Singh. Parliament of World’s Religions 2015 panel

‘Locating Gender Equality.’ (Photos courtesy Bhai Baldeep Singh.)

We framed the conversation by addressing the reasons commonly given for women’s exclusion from holding prominent public positions in the Sikh devotional realm: (1) the sexualization of the female body, (2) notions of purity and pollution, and (3) whether women have ample proficiency and knowledge to perform at the same caliber as men. Such reasoning assumed that women’s primary role was within the private realm of the household rather than the public sphere of performance. Our goal was to address the apparent hypocrisy between Sikh philosophy and praxis by asking, ‘If gender equality is a foundational Sikh principle, can women have equal access to perform all sevās within the Gurdwara?’

Panelist Dr. Harjot Kaur, a female Punjabi 3HO Sikh minister, musician, and medical doctor from Canada shared her own personal perspective on equality within Sikhī and her experience of gender-based discrimination within the Gurdwara, calling for greater support from men in power and institutional changes towards greater equitable practices.

I think that in order to empower our women to do more Kīrtan we need to have support. As an Indian Punjabi female doing Kīrtan in the Gurdwara, I need support from the executive [Gurdwara board]. I have to have the support that they are not going to turn my mic down. If I sit with the Granthi Sahibhan who does the Kīrtan, and I sing and accompany him, I have to have the support that they are not going to [also] turn off my microphone. I mean, those are the types of level of things that we [Kaurs] actually deal with.

So we need to change that perspective and prerogative by which we are viewing women and give them more power. It means taking the words of Guru Nanak and putting them into practicality. It means not just singing them every morning for Asa di Vaar. I find it so funny, that ‘Bandha Jameai’ is sung every single morning in Darbar Sahib, by the men, they are singing the Guru’s teachings, the Gurus words [but not putting it into practice].

We have to bring about this understanding and this change and we have to make the change practical. And then, by making it practical, we can truly say that Sikhī gives equal equality and Khalsa is genderless. Khalsa doesn’t have gender. Guru Gobind Singh didn’t say ‘are you a Singh or a Kaur?’ when he gave you amrit. He gave you amrit as a Sikh of the Guru and made you Khalsa. So I think when we look at these perspectives, we have to look at the challenges we faced as females. It is very encouraging that we see some new females coming forward. But the female jathas that were there from the beginning, they were hidden. There were some people that were in it, one or two [that were visible] but they became almost aggressive, or almost masculine in their nature, just to survive. So we have to change our cultural context by which we as Sikhs look at women as kīrtanies[female musicians].

Dr. Harjot Kaur’s testimonial illustrates the primary difficulties faced by Sikh women when playing kīrtan in the Gurdwara, even in the diaspora, whose microphones or staging may be adjusted to silence their voice or obscure their presence. Dr. Kaur points out that women have performed professionally in the past but have had to adopt a masculine public persona to fit into the male dominated rāgī culture. The erasure of female identities from the performative sphere of Gurbānī Kīrtan is a continuation of historical Indian norms that sexualize the public female body.

I. Sexualization of the female body

Dr. Francesca Cassio, Chair of Sikh Musicology at Hofstra University gave the panel’s keynote via skype, speaking about ‘Women in the Sikh Kīrtan Tradition: Past gender ideologies and the future of the tradition.’ She reflected on the sexual objectification of the female body, relating it to the Hindu-Muslim milieu of 17–19th c. North Indian classical music. During this period, the only female ‘professional’ performers in the public arena were courtesans (tawai’f-s) who would perform ‘ambiguous mystical-worldly love songs in royal courts and salons for male audiences.’ Cassio states, ‘it was the female persona of the singer and the secular context of the performance that shifted the meaning [away from devotional love and longing] toward a secular understanding. In the eyes of the male audience, the female body itself verbalized seduction.’ With this shift from the realm of Bhakti devotional love to a sexualized commodification of the female body the ‘Hindu-Muslim gender philosophy had a profound effect on women’s music-making until the first half of the twentieth century.’2727. Cassio recalls an interview she conducted with 11th generation Sikh kīrtania Bhāī Gurcharan Singh (b. 1915) when she asked him the reason women were not allowed to sing at the Golden Temple. 2828. Bhai Gurcaran Singh is the uncle of panelist Bhai Kultar Singh and granduncle of panelist Bhai Baldeep Singh View all notes His response reiterated the common twentieth century cultural perception that ‘the audience would be distracted by the presence of a woman on stage. People would look at her, without paying attention to the message of the banī’ (Cassio 245). Dr. Harjot Kaur echoed the effect of the male gaze on controlling and silencing women’s bodies and voices by sharing her own personal experience:

Sometimes you will notice in the Gurdwaras the stage will not be facing the women, Why? The Gurdwara committees are changing the direction of the stage so you [the sangat] don’t look at the women. So why is it that there is such an issue? I agree with Dr. Cassio that there is a sexualization of the female figure and the female form. One of the rāgīs that I really respect - he is a late rāgī, he used to play in the Darbar Sahib [Golden Temple] - he said to me, ‘It is just the shape of the woman.’ Even though the woman has a chuni and dupatta [scarf] covering her, that was an issue … If we look at the minority perspective of Sikhs being culturally as a minority, then we see that the Hindu majority, the Hindu patriarchal forces make women subjugated, or keep them suppressed. We as Sikhs, and Sikh men, we need to be empowered and empower our women, and as Sikh women, we need to empower our women, so we do not feel that same subjugation, and we do not fuel women with that same reference, or that same lens.2929.

Dr. Harjot Kaur relays her experience of men objectifying women as sexual objects and calls for both men and women not to condone such behavior. She frames the problem as systemic across Indian culture rather than specific to the Sikh religion and implies that the practice of veiling the female body is fueled by Hindu and Islamic notions of purity.

Hearing the first-hand accounts of gender-based discrimination within the Gurdwara, the male musician panelists expressed shock. They voiced that such conduct is contrary to the Sikh faith. Eleventh generation Hazoori Rāgī Bhai Kultar Singh stated that the objectification of the female form by the male gaze is contrary to Sikh praxis. Rather, those who are truly practicing Sikhī should view and treat women with the respect they would accord their own mother.

I don’t want to comment on the rāgī who said he doesn’t want to face women and do Kīrtan, because if he really had deep knowledge of the Sikhī then he would see his sister and mother in everybody.

I would like to comment on this, in Gurdwaras where one side is Bibian and one side is Gents. I think this is something new. If you go to any of the historical Gurdwaras in India, Darbar Sahib, Akal Takhat, Anandpur Sahib, Hazoor Sahib, there is no discrimination like that. People are sitting in whatever way they want to sit. There is no particular side which is given to ladies and gents. So this is something new. I don’t know who has started this, but certainly there should be no discrimination. Sikhī has no discrimination on the basis of caste, on the basis of financial status, no discrimination on the basis of gender. Why did we start this – ladies on one side and gents on another?

Hazoori Rāgī Sada Sat Simran Singh, (born into 3HO-Sikh Dharma and has been performing Kīrtan at the Golden Temple since early 2000) further questions the pseudo-spiritual mindset of those who sexually objectify the female body within the Gurdwara sphere.

If a guy says you should wear a chuni because your form makes me think of something else, I don’t think that person should be on a [microphone] in front of the public. That is not a person fit to be claiming any spiritual path, in my belief system. And that is what needs to be addressed. And it is always the same story.

Guru Arjan, the fifth Sikh Guru describes the mental state that is appropriate for a devotional service leader such as the rāgī. He directs his Sikhs to recite kīrtan with meditative concentration. ‘In the Kaliyug, the kīrtan is sublime (pardhana); The Gurmukh recites with concentration (dhyāna)’ in rāga maru solhe (GGS 1075). The musicians at the time of the Sikh Gurus were expected to recite the Gurbānī with meditative attunement to the divine, as a Gurmukh, rather than being a manmukh absorbed in their own worldly desires. However, socio-political changes from the Mughal Rule, to the post-Guru Era, to British Colonialism, and Nationalism during India’s Independence and economic liberalization have all affected the spiritual role of the Sikh devotional musician. Cultural norms attribute the male gaze not to the mentality of the ‘professional’ male Sikhs (granthīs, rāgīs, kathakārs, gīanīs) who are hired to serve priestly functions,3030 but instead to the female body as a sexual object and site of arousal that must be obscured, controlled, and protected. During my own research, this perspective was expressed to me in Patiala by Kashmir Singh, an engineer who has taught at Sikh Youth camps. When I asked whether he thinks women should be allowed to play Kīrtan inside the Golden Temple he responded, ‘It is cultural. Women do not have a history of performance on stage because [men] have sexual thoughts. Also for security it would be a lot to deal with’ (May 2009). 3131. Throughout years of interviewing prominent male Sikh musicians, a similar argument was given to support the exclusion of women from performing central devotional duties: ‘it is for women’s own protection.’

Doris Jakobsh in ‘Gender in the Sikh Traditions’ connects the control of women’s bodies to the cultural notions of izzat (honor) and sharam (shame) which value women’s virtue as upholding a family’s izzat, pride, respect, and dignity 3232. Jakobsh indicates that the ‘loss of honor is most closely aligned with female behavior’ and particularly controlling ‘female sexuality’ and protecting the ‘gift of female purity’ (601). In other words, a Punjabi male’s izzat is affected by their female relations whose ‘value is generally associated with notions of honour … modesty or propriety (sharam)’ (601). She states that ‘for this reason, as in all male-dominated societies, mechanisms of social control are firmly gendered’ (602). In these cases, to uphold a family’s izzat, women’s purity must be ‘protected’ by controlling their bodies, actions and voices.3333.

II. Purity and pollution

Notions of purity and pollution are embedded in Indian culture and dominant Indian religious constructs. 3434. Competing notions of purity and pollution have been projected onto a woman’s body – to be protected for its purity while at the same time shunned from ritual service due to its monthly menstruation cycle that ‘has the ability to pollute the most sacred of spaces’ (Jakobsh 600). While contrary to Sikh philosophy, Nikky Singh in Sikhism: An Introductionconfirms that in lived praxis ‘menstruating women are tacitly forbidden’ to carry the Guru Granth Sahib in the daily ritual of awakening (prakash) and resting (sukhasan). (118) Nevertheless, women particularly in the diaspora are given the agency to make their own choice whether to attend Gurdwara and perform sevāduring their menstruation cycle, though restrictions remain, particularly at the Golden Temple.3535.

The prohibitions against women serving the Guru to protect a sacred purity can be understood as antithetical to Sikh philosophy which at its core takes a balanced approach to dispel dualities between the sacred and profane, the spiritual (pirī) and temporal (mirī), purity and pollution, in recognition that all is part of the One (IkOngkar). Dr. Harjot Kaur Singh explains:

I think from a medical perspective, there is an issue as well. Because there is a cultural context in the religious spaces saying that a woman who menstruates or has a menstrual cycle is not clean, is not sacred, and therefore cannot be [in Gurdwara], and yet that makes me laugh because they will say ‘when you have your cycle you cannot bow before the Guru,’ ‘when you have your cycle you can’t do chawri sahib [wave the whisk] behind the Guru.’ It makes me laugh because during the time of Guru Amardas when Bibi Bhani was taking care of him, she had her menstrual cycle, when Guru Gobind Singh was alive in flesh, and Mata Jito Ji was there, she went and met with the Guru every day, she had her menstrual cycle. So albeit, I agree that we have to be careful and maintain [cleanliness with] those things, as women this is a natural part of life and we need to not approach it from the Hindu socio-cultural context. 3636. [We need to] bring it forward so we do give [women and men] true equality.

A primary component of Sikhī, as taught by the Sikh Gurus, is to live in the world as householders. Sikhs do not have renunciate monks and nuns, but instead promote living in the society, earning an honest living (kirat karo), giving some of those earnings to the community and those in need (vand chako), all through a meditative practice (nam japo) that always remembers the divine interconnectedness of all life. In this way, Sikhī emphasizes maintaining a connection to the Divine throughout one’s daily life of relationships, marriage, raising a family, and being of service to society. In this lived context, Sikh thought acknowledges the biological realities of menstruation, sexuality, and bowel movements, breaking down the binaries of the purity and pollution. The experience of being in the world is both temporal (piri) and spiritual (miri). Former secretary general of the SGPC, Kiran Jot Kaur states:

Sikhism defines man-woman on physical and spiritual level, the co-existence of temporal and the spiritual. On a physical level, men and women are different with different biological and social role. Nature prepares woman for procreation by onset of menstruation in puberty. Menstruation prepares the womb for motherhood, why is it unclean? Each day men (and women) produce, store and then excrete feces and urine, doesn't it make the body unclean? It is a paradox that motherhood is elevated to sainthood and the body preparing for motherhood is reviled as impure. Gurbānīinspires a person to develop feminine qualities for one's spiritual evolution. On the spiritual level Sikhī does not differentiate between male and female form (Aug 14, 2017). 3737.

Bhai Baldeep Singh cites Gurbānī to critique the female exclusion from sevā based on physical notions of impurity, turning the attention towards the mental or intangible ‘pollution’ of the mind, which he sees as perpetuating the issue:

This whole thing about the menstrual cycles and all this, that paradigm does exist around the Darbar Sahib, it’s utter nonsense. There is plenty of filth which is intangible filth which men carry into the Darbar Sahib every day. People like me have questioned that. It is not just the ‘tangible filth.’

Here Bhai Baldeep Singh touches the heart of the Sikh Gurus’ teachings which continually critique the hypocrisy found within purity-pollution paradigms, as expressed by Guru Nanak (GGS 472):

First Mehl:

Jio jorū sirnāvaṇī āvai vāro vār.

Woman has her periods, month after month,

Jūṯẖe jūṯẖā mukẖ vasai niṯ niṯ hoe kẖuār.

Yet impurity dwells in the mouth of the false; they suffer forever, again and again.

Sūcẖe ehi na ākẖīahi bahan jė pindā ḏẖoe.

They are not called pure, who sit down after merely washing their bodies.

Sūcẖe seī nānkā jin man vasiā soe. ||2||

Only they are pure, O Nanak, within whose minds the Lord abides. ||2||

Through Gurbānī, we can shift the conversation back to Sikh thought which looks beyond questions of pollution related to the physical gendered body and reframes it within the mental state of its practitioners. It causes us to examine the virtues that should be embodied by a Sikh religious leader, indicating that purity of mind and action be the primary qualifications for ‘professionalism.’ Insiders have experienced corruption, hypocrisy, and abuse within the rāgī ‘profession’ which makes it necessary to question how we can elevate the standard for greater equality, dignity, and respect. To do so, it becomes helpful to contextualize the changes that have occurred within the ‘rāgī profession’ since the times of the Sikh Gurus.

III. Pedagogy, praxis and proficiency in the rāgī & rabābī ‘profession’

Since its inception in the early 16th century, Gurbānī Kīrtan was professionally sung by male musicians in various Indian classical music styles (dhrupad, chantt, and later khayal) in rāga melody. Initially male Muslim ‘professional’ musicians called rabābīs, were employed to sing Gurbānī Kīrtan in communal gatherings or satsang. The fifth Guru, Guru Arjan, then created a Sikh class of male kīrtaniamusicians patronized by the Guru and royal courts. The partition of the Punjab in 1947 created Pakistan and caused a removal of the rabābīs from Sikh devotional music. Due to the 20th c. colonization of Indian religio-cultural spheres and economic liberalization, the profession became dominated by a new class of ‘professional’ male rāgīs, singer of rāgas. However, it was in the early twentieth century, during British colonialism, with the advent of recording and playback technologies that Gurbānī Kīrtan began to be sung in popular music styles taken from film tunes, tailored for a listening audience who appreciated this new lighter musical aesthetic. While men still controlled the devotional sphere of Gurbānī Kīrtanproduction, the diversifying effects of media technologies and the modern agendas of social reform enabled a few notable female musicians to find popularity through media technology, as discussed in Dr. Francesca Cassio’s award winning paper ‘Female Voices in Gurbānī Sangit and the role of the media in promoting female kīrtanie’ (2014Cassio, Francesca. 2014. “Female Voices in Gurbānī Sangīt and the Role of the Media in Promoting Female Kīrtanīe.” Sikh Formations: Religion, Culture, Theory. 10 (2): 233–269. doi: 10.1080/17448727.2014.941203 [Taylor & Francis Online], , [Google Scholar]). She identifies the history of women in Sikh kīrtan and how women’s roles have changed due to the advent of recording technology, Sikh reform, 3HO/Sikh Dharma egalitarian ideologies, and now media technologies that highlight and promote these female singers. While there are records of women receiving kīrtan education in institutions since 1892, they were not developed as ‘professional’ singers of rāga (rāgīs) but rather amateur musicians and music teachers.3838. A predominance of male teachers and voices increases the need for what Cassio identifies as a ‘female sonic’ model for Gurbānī Kīrtan sung in dhrupad, not just the simple jyotian styles or the popular courtesan genres of thumri, and ghazzal (Cassio 24).

In the twentieth century, changing attitudes about women’s roles in the musical realm as well a newly emerged ‘market as patron,’ gave rise to new ideas of what constitutes a ‘professional musician.’ Musicians no longer needed the fifteen to twenty years of serious apprenticeship and courtly patronage to be considered ‘professional’ by the public-as-patron, but could now learn popular tunes, record an album, and become a ‘professional musician’ based on public demand. Today this trend continues, with ‘professional rāgīs’ being hired, based not on their musical aptitude or qualification, but their popularity. While this transition has had a positive effect in promoting female kīrtanie, (Cassio 2014 it keeps them excluded from the professional realm, and also calls into question how professionalization has affected the spiritual-aesthetic intent of the Gurbānī Kīrtan music and musician.

(De)Colonizing Sikh institutions, pedagogy, and praxis

Education either functions as an instrument that is used to facilitate the integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes ‘the practice of freedom,’ the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world. (Friere 34)

Gurbānī Kīrtan has been carefully cultivated and attentively passed down from teacher to student (guru-shishya) through sina-bi-sina or heart to heart transmission for centuries. But the last hundred years have witnessed a loss of traditional pedagogy and its musical modes due to the late 19th and early twentieth century British colonization and subsequent reform movements that viewed the teacher-student relationship as incompatible with new avenues of musical transmission and technological reproduction. (Subramanian 2008 Originally there were three primary institutions of learning or taksals that produced Gurbānī Kīrtanexponents: the Amritsar taksal in the District of Amritsar, Sekhwa(n) taksal in the District of Firozpur and Girwari taksal in the District of Hoshiarpur, the latter two being initiated in the early 18th c. by Bhai Dharam Singh of the Panj pīyāre after Guru Gobind Singh died. Additionally, between 1765 and 1833 there were more than 70 bungas on the walkway surrounding the Golden Temple, belonging to individuals and communities as places to house pilgrims or as places of learning. However, in the twentieth century the bungas were demolished. This was partly due to the changes introduced during British colonization. The British removed patronage that had previously supported Sikh schools of learning, and replaced them with British-run educational institutions. However, this new methodology for teaching music based on a Western pedagogic approach simplified the musical styles and relegated oral knowledge transmission to being perceived as an antiquated and pre-modern method.3939.

Due to India’s changing socio-political and technological landscape over the last two hundred years, the Sikh intangible inheritance that was the Gurbanī Sangīt paramparā has become near obsolete and obscured by modern forms. The famous rāgī Bhai Samund Singh told Bhai Gurcharan and Bhai Avtar Singh in 1971 that ‘knowledge of kīrtan has come to an end.’ (Singh 2008 Singh, Bhai Gurcharan.2008. Kirtan Nirmolak Heera & the Art of Music. New Delhi: Gurmat Printing Press. [Google Scholar], 58)

By the end of the nineteenth century, native elite Sikh Singh Sabhareformists re-formed Sikh philosophy, identity, and devotional practice to establish Sikhism as an independent religion, and Sikhs as modern citizens of an independent Indian nation. In an effort to create a ‘pure’ Sikh (musical) identity, they removed elements perceived as transgressing Sikh-Khalsa normativity from Sikh socio-religious institutions. The Gurdwara Act of 1925 removed the non-Khalsa mahants and udasis who had managed the Harimandir Sahib and other historic Gurdwaras while the Mughals were hunting the Sikhs. In their place the Khalsa-run Gurdwara management committee, the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC), was established.

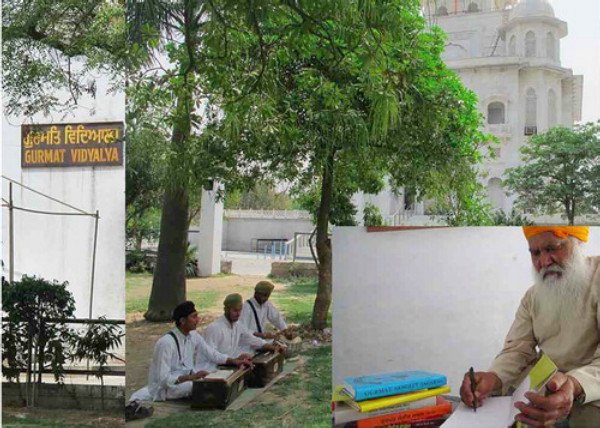

Today all the historic Gurdwaras in Punjab are managed by the SGPC while those in Delhi are managed by the Delhi Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (DGPC). These institutional bodies also run some of the Gurmat Sangīt vidyālā schools and employ their graduates as rāgīs within the historic Gurdwaras and at the Harimandir Sahib, or help them gain employment at Gurdwaras in the Diaspora. Late Principal Dyal Singh (1934–Feb 2012) of the Gurmat Vidyālā at Rakab Ganj Gurdwara, Delhi, imparted to me that there were knowledgeable patrons of sangīt and Gurbānī, until the creation of the SGPC in 1925, when as elected officials they no longer maintain nor invest in traditional gian (knowledge):

The puratan sangīt vidyālās (ancient music training centers) were run by the nirmalā, udāsī, gīānī(knowledgeable ones). In 1925, the SGPC was created and began to manage the gurdwaras, including centers such as Harimandir Sahib and Tarn Taran, which they took over from mahants. The election system came in the Dharma. These people had no idea about Gurbānī gian(knowledge of Gurbānī) or about sangīt gian (knowledge of music), but they were all about money and power. They didn’t pay much attention (dhyan) to the Gurbānī or sangīt di gur shaile (music in the Guru’s style). The older ustāds (masters) passed away and there weren’t any new educated people to take over … The Gurdwaras are getting money from the donations, they are not using it towards teaching [Gurbānī Kīrtan] or doing research. The puratan maryādā (tradition bearers) used to love sangīt, do research, and practice on their own. This is all over now. The people who are still around the Gurdwaras haven’t done the whole study the way they used to do it and they don’t know much about sangīt or rāga gian. (Interview by Nirinjan Kaur with Principal Dyal Singh, translated from Punjabi, April 2, 2011)

Students practicing Gurbānī Kīrtan outside of the Gurmat Vidyala, Rakab Ganj Gurdwara, Delhi. Principal Dyal Singh signing the Gurmat Sangeet books he authored. (2011 Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur. 2011. Sikhism: An Introduction. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]) (Photos by author.)

While the first-generation members of the SGPC maintained a high level of spiritual-aesthetic integrity with regards to Gurbānī Kīrtanpatronage, pedagogy, and scholarship, over time the SGPC became dominated by political agendas as elected officials and identity politics overruled spiritual-aesthetic integrity. A lack of responsible patronage by the SGPC and Sikh panth caused the memory, quality, and heritage of Gurbānī Kīrtan and its practitioners to diminish. Bhai Gurcharan Singh attributes this current state of affairs to the fact that ‘religion started suffering at the hands of politics.’ (Singh 2008Singh, Bhai Gurcharan.2008. Kirtan Nirmolak Heera & the Art of Music. New Delhi: Gurmat Printing Press. [Google Scholar], 59) Modern reforms in the name of democracy often resulted in decisions made by elected committee members with no education in the spiritual-aesthetic integrity of the tradition.

The Sikh musicians and scholars I have interviewed (some employees of the SGPC and DGCP as head teachers at the vidyālāschools and rāgīs at Darbar Sahib) noted the committees’ overall lack of knowledge and patronage as the primary reason for the cultural amnesia of spiritual-aesthetic modes of Gurbānī Kīrtanpedagogy, scholarship and praxis. The late Principal Dyal Singh addresses the impact that twentieth century politicization of Gurdwara Management Committees has had on Gurbānī Kīrtan, lacking the patronage necessary to maintain the necessary high quality standard.

The Prabhandak committees, the two committees [Shrimoni and Delhi] they have crore rupaieea, so much money coming in through donations. The people who have that power, they don’t have that knowledge or experience of Gurbānī. So how could you value something if you do not know yourself? They are just trying to fill in [rāgīs at Gurdwaras] it is going just like that … Because of this, great rāgīs are not there anymore.(Principal Dyal Singh, April 2, 2011 Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur. 2011. Sikhism: An Introduction. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar] translated from Punjabi)

The view that monetary concerns and politics have diminished an emphasis on training highly skilled musicians was also affirmed by the Head Rāgī (at the time of the interview) at Harimandir Sahib, Bhai Narinder Singh Banarsi. Singh affirmed that there are set requirements for musicians to be given employment as Hazoori Rāgīs (resident musicians at the Golden Temple), however, as elected officials, the efforts of SGPC members are focused on re-election rather than preserving the quality of the music and musicians. ‘The committees are political. They are politicians with no efforts to improve the traditional method of kīrtan.’ (Interview by Nirinjan Kaur with Bhai Narinder S. Banarsi April 24, 2011)

Bhai Narinder Singh Banarsi at his home in Amritsar, April 24, 2011. (Photo by author.)

This sentiment was also echoed by Bhai Kultar Singh on the 2015 PWR panel.

The main trouble we have today, is that the people who know are not able to change it, and the people who can change, don’t know anything. So the main blame I would give is to the system of people who come into control, controlling our entire community. The main reason is that we have elections instead of selections … Since we have begun to elect our candidates, this problem started, the downfall of Sikh values started from that day … When the Shiromani committee was formed, that was the first model for election when the voting was done. They approached Sant Baba Attar Singh Ji Mastuana-wale who was an undisputed saint at that time. And they told him, Maharaj, can you come and do Ardas? We have formed Shiromani committee, and he refused to do that, and they asked him the reason why. He said, “my reason is this, at the time when the Mahants were doing bad practice and the panth wanted to throw them out, the panth has succeeded, but the time when the panth will have to throw you out, the panth will be defeated.” That is what he said, Sant Baba Attar Singh. And it is proving to be true, that it is difficult to throw these people out who are controlling our shrines.

While the musicians at the Harimandir Sahib are lauded as ‘professionals’ who represent the pinnacle of Gurbānī Kīrtanproduction, there are not many contemporary Hazoori Rāgīs who uphold the spiritual-aesthetic standard due to lack of thoughtful patronage and the political nature of the selection committees:

The standard has become low. The proper people are not selected. The subcommittee has a standard – they have a paper form to fill from. What is age, qualification (school and sangīt), to be filled up by contestant. What rāgas of SGGS have you learned, how many tālas can play, from where you have taken training, about 15–16 columns. When they fill it up we come to know what he knows. But according to this there are not so many people who can pass the test, because when we read the papers we come to know who is eligible. One hundred applications come for selection. They write that they know this and this, but when we ask them to sing what they know, they can’t sing properly. (Interview by Nirinjan Kaur with Bhai Narinder S. Banarsi April 24, 2011)

Even though the Gurbanī Sangīt paramparā maintained a high-level of scholarship, modern Gurbānī Kīrtan has become stigmatized as a musical genre sung by uneducated musicians who market their music for commercial popularity.

The lack of patronage and respect given to Gurbānī Kīrtan has filtered down to the educational institutions and rāgīs. The new institutional format has been created to churn out professional rāgīs, who are most often guaranteed a position at a Gurdwara whether in India or the diaspora, regardless of musical ability or spiritual-aesthetic intent. Bhai Baldeep Singh explains:

The purpose of these vidyālās was never to create a pedagogic model which would help the tradition to live on, and even flourish - the graduates were just trained to be able to undertake the Gurudwara rituals … These places have focused on their creations - their concoctions without ever enthusiastically endeavoring to imbibe the memory of the Gurbānī Sangīt paramparā, first without which one is not introduced to the traditions’ perspective, logic and philosophy and the due attendance of its protagonists (Sep 18, 2013 email communication).

Prominent teachers at the vidyālā institutions along with well-respected Gurbānī Kīrtan musicians acknowledge that the modern institutions do not provide the proper patronage to sufficiently train rāgīs. While only men are allowed to enter these vidyālās, which are created to train rāgīs to take the positions at various historical Gurdwaras, women are studying with different teachers and at universities and are gaining high levels of proficiency. Due to these various factors, there is a clear need to revamp the educational systems that train Sikh musicians as well as the process by which musicians are selected to play at Darbar Sahib. Rather than asking that women be admitted to the current vidyālā institutions as they stand, it appears we need to envision and develop a new paradigm.

Taking the history of the rāgī profession into account, we see that while it has been historically gendered, the current standard for who can play Gurbānī Kīrtan at Darbar Sahib should not be based on gender, caste, or creed but instead on musical aptitude and one’s ability to maintain the integrity of the spiritual-aesthetic genre. The lack of responsible patronage and the politicization of the musical sphere has caused musicians not to seek out the scholarship of the Sikh paramparā. Instead they have employed their own perspectives through a distorted colonized logic that problematically mask contemporary problematic practices as ‘maryādā’. Today the SGPC continues to use the notion of ‘maryādā’as a reason why women are unable to participate in kīrtan sevā at Darbar Sahib, and why there should be no debate on the topic.

Debating ‘Maryādā’: A colonized tradition?

Discovering himself to be an oppressor may cause considerable anguish, but it does not necessarily lead to solidarity with the oppressed (Friere 49).

The request for women to be permitted to perform all sevās at Darbar Sahib and to be given equal opportunities in Sikh praxis continues to be taken up by Sikh diasporic individuals, organizations and outlets such as Kaur Life and Sikhnet.4040. In 2018, Parveen Kaur, a High School student from Australia created a petition ‘Allow women to do kīrtan seva at Harimandir Sahib’ with other petitions also created online through ipetitions and change.org. View all notes In the summer of 2017, Camp Gurmat, an annual camp for Sikh youth hosted by Guru Gobind Singh Foundation outside of Washington, D.C. made gender equality that year’s camp theme. Their call for women to play inside the Golden Temple went far and wide and was picked up by television and online media outlets in India and the diaspora who debated the issue.4141. Their request was aimed at the current Jathadar of the Akal Takhat, Gyani Gurbachan Singh, who is responsible for such decisions. Yet when contacted by the Times of India on July 27, 2017 Rana, Yudhvir. 2017. “Why Women Not Allowed to Perform Kirtan in Golden Temple Sanctum Sanctorum.” Times of India, July 27. [Google Scholar], he responded ‘I have no opinion on this issue.’4242. His non-response spoke to the dismissive manner in which the request for women to have equal opportunities within Sikh devotion has been handled and silenced.

The next day, the Hindustan Times reported that SGPC chief Kirpal Singh Badungar ‘passed the buck to the Akal Takhat Jathadar’ stating that it is an issue of ‘maryādā’ or tradition and therefore ‘the SGPC has no role in allowing or denying such rights to women’ (July 28, 2017 HT Correspondent. 2017. “Why Can’t Women Conduct Kirtan at Golden Temple? SGPC, jathedar cite maryada.” Hindustan Times, July 28. . [Google Scholar]). This statement prompted the Akal Takht Jathadar to publicly affirm their stance that the ‘‘kīrtan maryādā’ at the Golden Temple is centuries old and cannot be altered easily.’4343. Here, Balvinder Kaur is touching on how religious leadership has controlled women by making them ‘the object, not the subject of discourse’ (Levitt 1993Levitt, Laura. 1993. “Reconfiguring Home: Jewish Feminist Identity\ies” Ph.D. diss. Emory University, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar], 172). Men have historically served as Sikh ‘ritual experts’4545. – granthis, kathakars, kīrtankars, rāgīs, members of the SGPC, and Akal Takhat Jathadars – giving them the authority to interpret the Guru Granth Sahib and create religious normative prescriptions such as the SRM. Appeals to the maryādā have now become the official SGPC reason for why women should continue to be barred from performing Gurbānī Kīrtan in Darbar Sahib, continually silencing the female voice.

Appeal to tradition: maryādā, paramparā, and rahit