“Go to India! There is a yatra this summer that Sangeet is putting together that will take you to one of the holiest places on Earth!”

I was told this by a woman I adored, my spiritual teacher, Guru Simran Kaur. She was barely old enough to be my mother but to me she was the mother of all mothers. Her life was fraught with cancer and illness, but her compassion and love for others came from a strength I have not seen in anyone else. I met her in the weeks after my father died in 2002. We met at a women’s meditation circle while I was in the beginning stages of a deep grieving period. Our eyes met, a bright welcoming smile crossed her face and we were bonded until her death in 2013. She was from New Jersey; Catholic born and bred. She almost became a nun but chose nursing instead. She fell in love, got married, had a child, got divorced, and ended up in Phoenix as a single mother with cancer. She survived that first bout; there would be a second and then a final third.

The women’s full moon meditation took place in the back yard of an American Sikh named Sangeet Kaur Khalsa. I knew Sangeet through my mother and younger sister, Kathleen. The meditation was made up of women sitting on the ground in a circle chanting a healing mantra while other women who needed healing laid on the ground in the center. That night I found myself lying in the center of that circle.

I have discovered that with grief- whether due to a death or from abandonment- you have two choices: run away and hide or sit with it and heal. I have done both and neither one was easy. The second choice was to heal through kundalini yoga and meditation which is how I ended up in India in the summer of 2006. Guru Simran Kaur, through her own grief, found the Sikh faith and became as dedicated to it as she had once been to the Catholic church. She was basically a nun in Sikh clothing-wearing only white, living in a tiny house owned by the Sikh ashram across the street, reading from the Sikh sacred scripture daily, and making sure that all her children were keeping up with their spiritual practices as well.

“How much? How expensive is this yatra?” I asked her.

“Money will come! Just ask the Guru to make it happen!” she told me.

When she said, “ask the Guru,” she did not mean herself. Her name is Gurmukhi for the teacher of prayer. Guru means teacher, Simran means prayer. She was not a Guru but she was a teacher of those who were on their spiritual path. When she would say, “ask the Guru,” she literally meant ask one of the ten Gurus of the Sikh faith. Kind of like asking Buddha, Jesus, or the Prophet Mohammed for help.

The summer yatra was six months away and I was at the beginning of a six-month kundalini yoga teacher training course which was costing me almost as much as a trip to India. How was I going to pay for both things?

“You are meant to be on that yatra! Call Sangeet and tell her you are going!” She answered.

A yatra is traditionally a spiritual journey to a significant holy site, usually in India. It often involves a group of people and is hopefully well organized by a guide. In the case of this yatra, it was organized by Sangeet Kaur from Phoenix and Siri Vishnu Singh from New York City. You didn’t have to be a Sikh to go on the yatra, many of us weren’t, but it was helpful to be on a spiritual journey while living a yogic lifestyle. Guru Simran was right, the money to pay for it came and everything fell into place.

By the time I arrived at the airport to catch my flight to Los Angeles and onto Tokyo, Singapore, and Delhi, I was in the best physical shape of my adult life. Months of yoga, hours of meditation and breath work, five weeks hiking around the hills and beaches of Marin County just north of San Francisco that summer. I was ready for the yatra!

Or so I thought.

India has a way of throwing your challenges back into your face, forcing you to look at them for what they really are: Maya. India is an intense country. It is not for the weak, or for those who like things to be clean, or those who enjoy daily showers, or indoor toilets, or stop lights and speed limits, or have a dislike of wild bands of monkeys, or an aversion to elephants as a form of transportation, or ornately decorated cows in the market place (please do not feed them, you will regret it!)

Our yatra was going to be broken into two different trips: the first part was traveling high into the Himalayas to a sacred place called Hemkunt Sahib on the edge of a small lake surrounded by sharp, pointy mountain peaks. The other side of those mountain peaks was Tibet. The second part was traveling to Amritsar, the location of the Golden Temple, in the northern state of Punjab near Pakistan where it is hot-really, really, hot. The kind of humid heat that makes the ink in a ball point pen congeal and electronics to no longer function.

Hemkunt Sahib is somewhere between 15,000-16,000 feet in elevation depending on who you ask. You do not get off your plane and travel straight to Hemkunt; it takes days of travel before you can finally ascend the mountain. We started our yatra with two days in a fancy hotel in New Dehli to relax and recover from our jet lag. From there we took a rented bus up a winding narrow road to the city of Rishikesh. Thanks to both the Beatles spiritual journey in 1968 and the amount of yoga centers and ashrams that reside there, Rishikesh is known as the “Yoga Capital of the World.” It sits on the Ganga River (known as the Ganges in the West) at the foot of the Himalayas in northern India. Rishikesh is a place where you see both light and darkness in people. I saw dozens of people dipping in the river with reverence to their spiritual deity. I also saw a ghost looking woman from Austria following her Sadhu drug dealer while begging him for her next fix. She reminded me of the animated bride in Tim Burton’s film Corpse Bride. Her appearance was troubling to both myself and the two American women I was standing with. When one of them asked her if she needed help the ghost woman turned to us, said all was well, and vanished into the crowd leaving us bewildered.

Unlike other countries where feral cats or wild dogs roam the streets, India has free roaming cows. They are often adorned with colorful paint and ornamentation hanging from their horns and necks. At the same time, they are thin, ribs showing, with starvation in their eyes. As I was leaving a restaurant in a market place full of vendors with my friends, a young thin calf came up to me, huge brown eyes gazing up into mine longingly, just as a man pushing a produce cart was within arm’s reach. I stopped him and purchased a large pomegranate before feeding it to the calf. Within seconds of what I thought was my small act of kindness, a stampede of street cattle came barreling towards me and the guy with the cart, causing mayhem and much cursing from the venders in a variety of languages. The market place was now jammed with hungry cattle.

“Stupid woman!” shouted at me by our Indian guide. “You don’t feed the cows! Ever!”

“But she looked hungry,” I replied.

“Do not feed the cows!” he said.

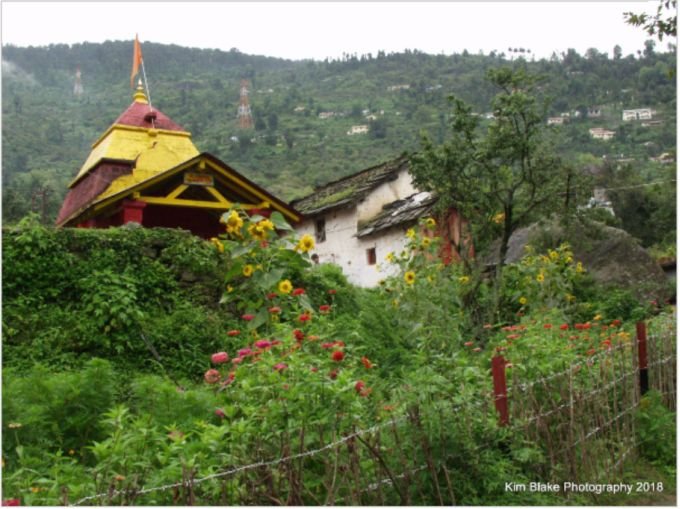

The next leg of our journey took us higher into the foothills of the mountains to a village called Joshimath. The village was built into the lower part of the mountains; its buildings were painted bright yellow, orange, blue, fuchsia, and purple, in stark contrast to the dark gray sky. The residents of Joshimath looked more Tibetan than Indian, with a mix of men and women in saffron robes, and children in their school uniforms. We were there for two nights after monsoon rains caused an avalanche to block the road to the next village. Once the road was cleared we made our way further up the mountain. Large chunks of the two-lane road were washed away. Smashed vehicles could be seen from our bus windows at the bottom of the cliff below. There were twenty-seven of us on that bus. Each of us holding our breath or praying that the road would hold up long enough for us to make it to the next village safely.

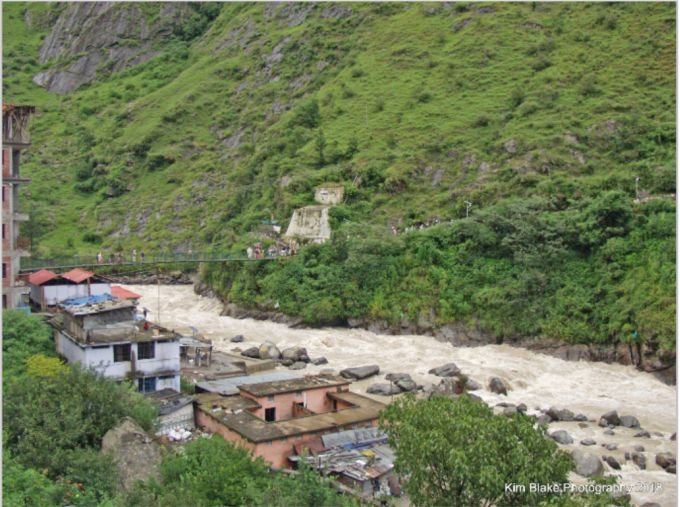

The road ended at a village called Govindghat,, located at the confluence of the Alaknanda and Lakshman Ganga rivers, at 6,000 feet in elevation Our bus parked in a muddy lot yards away from the shelter of buildings. It was raining and every step I took was submerged into puddles of muddy water. The only women in the village were the ones who came off our bus. We got stares and were watched as we meandered through the market, making our way to our rooms inside the large Sikh Gurdwara on the edge of the river bank. Govindghat was not like Joshimath or Rishikesh. It was a tiny village and our last opportunity to purchase basic supplies before crossing a narrow foot bridge over the river.

The next morning after breakfast, we continued our trek for hours by foot or horse to the next village called Govinddham, at 10,000 feet in elevation. In 2006, Govinddham had electricity for only six hours a day and only one public phone. A bucket of hot water for bathing cost ten rupees and was boiled over an open fire. The walls of our rented guest house were paper thin and there was no shower or bathtub. A spigot next to the bathroom toilet was all there was for water. I mastered the art of the bucket bath by mixing two buckets of boiling hot water with the ice-cold water that sputtered from the spigot. By using a plastic measuring cup that was left on the bathroom floor for just such a purpose I managed to wash myself sufficiently.

Ten thousand feet in elevation is when the signs of altitude sickness started to show up in some of the people in our group. At higher elevations it is called Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), with symptoms resembling a case of "flu, carbon monoxide poisoning, or a hangover," according to a pilot study published in 2013 in the Indian Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine.

There is no way of knowing in advance if you are prone to AMS until it happens. The only way to recover from it is to descend to a lower elevation. Our group spent several days taking hikes in the nearby Valley of Flowers National Park to acclimate ourselves to the altitude. The park was breathtaking with multitudes of flowers sprouting from the lush green landscape. The surrounding mountains were dotted with snow, the air was crisp, the sky misty blue.

After a couple of days, we were ready to ascend Hemkunt Sahib. The route to Hemkunt is a frightening vertical zig-zagging path on the side of the mountain. I rented a horse after breathing while walking became too much of a challenge. It never occurred to me that it would soon get worse.

Up, up, up I went, soon realizing I was alone on the back of a horse on the narrowest of stone paths in the rain, traveling up a sharp incline to a Sikh Gurdwara in the Himalayas while being passed on foot by devout shoeless Sikhs, both men and women. often older than I was, and much better dressed. It was a misty drizzle as I ascended. The heavy rains from the previous days had created miniature waterfalls that ran down the steep walls of the mountain creating rivulets across the path I was traveling. It was August, but everything was wet and winter cold. I do not recall how long it took me to arrive at the end of the path where the Gurdwara and lake were-time for me had stopped. I got to the top and was helped off my horse by a man, never seeing him or my horse again.

The ground was rough with patches of snow and dead grass. The land around me was ringed with mountain peaks that resembled jagged shards of glass. Traditional Sikh orange and blue Nishan Sahib flags flew from poles on many of the peaks in the distance. Hemkunt Sahib rests in a small valley, the Gurdwara sits on the edge of a mirror-like lake at its center. The fog gave it a dream-like quality, shrouding everything and making it hard to find my way around. I found the langar hall where the meals were prepared and served. A handful of people from my yatra were inside so I joined them at a table. Every Sikh Gurdwara in the world provides people in their community with langar- a free vegetarian meal- regardless of race, religion, gender, or caste. This tradition was created by Sikh founder Guru Nanak. That day they served langar from a huge steaming hot caldron: dahl (lentils, legumes, and beans) and chapatis- the Indian version of a tortilla. The room we were eating in was dark, with only the open doorway lighting it. I had eaten dahl at many langar halls in gurdwaras around the United States, but this dahl had so much salt in it that I could not choke it down. My only food was the wasabi peas and protein bars I had in my purse.

While sitting in the langar hall I began feeling the symptoms of AMS: nausea, extreme headache, uncontrollable shaking from the cold, disorientation, and in my case, lots of uncontrollable crying. As I stepped out of the langar hall into the cold rain I could not find anyone I knew. Everyone around me was a stranger. I walked in the rain until I found the lake where men were stripping down to their undergarments and dipping into the freezing cold water. Many shouting “wahe guru ji ka khalsa, wahe guru ji ki fateh!” as they plunged themselves under the water.

The women dipped inside a private room that resembled a cavernous mining shack built at the corner of the lake. This gave the women privacy from the men. It consisted of four wooden slat walls, a roof, and the cold hard earth for the floor. The walls came down just above the water line, allowing the lake water to emerge under the longest wall. It was very dark. The only light came streaming through spaces between the slats of the walls and reflected off the water’s surface. A Sikh woman who was traveling on our yatra found me weeping along the lakes edge and pulled me inside the women’s dipping area. She began to chant as she stripped me down to my pale cold skin and guided me into the water. My head was in so much pain that all I remember was her pushing me down from my shoulders under the freezing water one, two, three times as she chanted, then out of the water she pulled me, into a dry towel, and back into my clothes. My weeping did not end and neither did the cold I felt deep inside my bones

The rest of my time on the mountain is so blurry that it only comes to me in dream-like snap-shots. Somehow, I ended up with a small group from our yatra in the living quarters (a bedroom basically) of one of the men who lived there and guarded Hemkunt Sahib during the summer. Heavy wool blankets were piled on top of me as I laid down in the corner. Our guide brought me hot chai tea, but nothing could relieve my cold. It was as if my entire body was frozen from the inside out. My head pounded, my body shook, the nausea continued, and I could not stop crying. I made my way outside to a fire encircled by elderly Indian Sikh men. I must have been a sight; an American woman with blue hair and dirty clothes, crying uncontrollably. Panic welled up inside of me, so I made the decision to get off the mountain immediately. I could hardly communicate by this time but somehow, I found Siri Vishu Singh and pleaded for him to get me off the mountain before I passed out. He spoke with the men who were sitting around the fire. They told him that the horses were gone. The only way down was to be carried down in a basket on the back of a small Tibetan man. Had I not been out of my mind and weeping, I would have questioned this plan.

I am not entirely sure how the instructions were given to the man with the basket; I did not speak that language. Next thing I knew, I was being tucked inside a large basket strapped to both the man’s forehead and his torso. My knees were crammed up to my chest, my purse and camera stuffed against my side, a blue plastic tarp was draped over me to protect me from the rain. Off we went, down the mountain in the rain over the same wet stones, on the edge of the same steep cliff I had crossed on my horse hours earlier. What do you call a man who carries you on his back in a basket for hours in the rain down a steep mountain? Savior? Hero? I never got his name, we never talked. For the sake of the rest of this story I will refer to him as Steve. Steve wore loafers, khaki pants, and a heavy winter sweater. No rain boots, no rain coat, no hat to keep his head dry.

He kept a steady pace down, down, down the steep path, for hours. The rain never let up as he descended forever downward like a mountain goat. I was still weepy at the beginning of our trek, then I tried to relax and sleep. I drifted off for a time but eventually found myself awake and nauseous. This time it was motion sickness, the feeling that any minute I was going to vomit inside my basket. I peeked out from under the tarp and saw an older American woman who was traveling in our yatra. She was with a local guide who was assisting her on her hike down the mountain path. I called out to her for help.

“Maureen!” I cried. “I need to get out of this basket! I am going to vomit! Help!!”

Maureen caught up with Steve and made a motion for him to stop. We just happened to be in front of a tea stall on the mountain side of the trail. She motioned for her guide and Steve to follow her inside. They were confused and began to converse with each other in frantic voices, most likely not sure why we were stopping. Were we angry with them? Steve would not let me out of the basket.

The tea stall was open on three sides with a roof and a counter at one end. Near the counter was a table of men drinking tea. I shouted from my basket, “Do any of you speak English?” One man replied that he did and came over to our confused little group. I asked him if he and our two guides had a language in common. After a moment of conversation with them he said that they did.

“Great!” I said. “Please tell my guide that I have motion sickness and feel like vomiting. I need to get out of this basket and walk the rest of the way to the village with him.”

He promptly translated what I had said and soon the two guides exclaimed something agreeable in unison and I was set free. I stretched out my legs before Steve and I continued our trek in the rain for several more hours. By the time we reached the village, the sun was low in the gray sky and the rain water was up to our shins. He led me to a restaurant in the village. Waiting for us with hot chai and Steve’s payment was our yatra guide. Once Steve was paid, I turned to give him a hug of gratitude. With a look of disgust, he pushed me away and scurried out into the rain.

“Stupid American woman! Don’t go around hugging people in our country! He doesn’t want your hugs, only your money!” The guide scolded.

I laughed. I felt relief from the warmth of the hot chai and from being off the mountain and out of the basket.

Weeks later, as I was standing by the baggage carousel in the Phoenix airport waiting for my suitcase to appear, I called Guru Simran Kaur.

“Sat Nam!” she answered. “I was praying for all of you while you were away! How was the yatra?”

“I was carried down the mountain at Hemkunt Sahib in a basket on the back of a tiny man in the rain, cursing your name the entire time!” I told her.

“Ha! I know you were, I could feel all your curses while I prayed!”