|

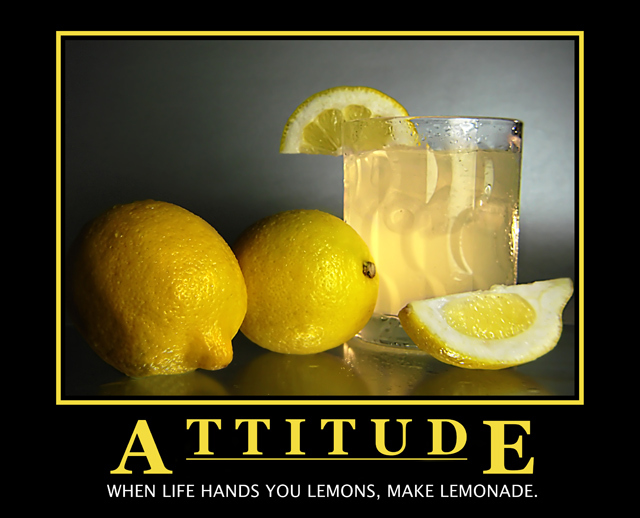

WHEN LIFE GIVES YOU A LEMON | ||

|

It doesn’t take long to learn that life is not always a bed of roses. In fact, it seldom is and even then only apparently so, and perhaps only to those who do not feel and cannot think. Also, roses don’t come without thorns. If life is a bowl of cherries, they never come without pits. Nevertheless, as thorny as life is, it is better than the alternative. How, then, to deal with the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, the pits and thorns that accompany life, even in the best of times? Walking along the mountaintop is easy and liberating, but the question is how best to navigate the connecting valleys of despair. What kind of an attitude will carry one through the muck and the suffering of life? Sikhs have a cliché for it — charhdi kalaa. Like all clichés, it takes much more than a sentence or two to explain, and even then I have never seen a satisfactory exposition of it. The cliché is pithy, true and terse, the explanations verbose, rambling and incomplete. I have seen charhdi kalaa translated literally as “eternal optimism” or “cheerfulness.” Cheerfulness in the face of certain disaster seems an anachronism, an impossibility that can only reflect an unenviable level of stupidity. Perhaps such optimistic happiness would be possible, but only in a state of numbed mindlessness. And most people are neither willing nor able to suspend their feelings and thoughts quite so completely or successfully.

History tells us that two Sikh Gurus were martyred in the cause of freedom of religion. When Guru Arjan and Guru Tegh Bahadur accepted torture, suffering and finally martyrdom, they still rejoiced in God’s will. The last words of Guru Arjan as he underwent inhuman torture, history tells us, were of cheerful acceptance of the will of God. He did not lament his suffering, nor did he think that God had abandoned him. He did not complain, “God, why have you forsaken me?” But this does not mean that the Gurus were unfeeling of pain. If they felt no pain, they would understand no suffering and would have little to teach us. They showed the way to accept the ultimate in suffering and transcend it with grace, humility and dignity. There is never any pleasure in suffering; the secret lies in accepting the inevitable with good grace. Sikh history contains so many examples of martyrdom that their recounting here must surely be incomplete and inadequate, so I will not attempt it. No Sikh, however, can remain unaware of that history; it is briefly recounted at every prayer, every day. Each of us must die — that is inevitable — but death is never welcome to anyone except the suicidal. Normal people rarely look forward to the end of life, and death remains for most the ultimate in mystery and uninvited suffering. It is in the manner that one accepts the reality of death that courage is measured. No one can walk away from death or suffering, defeat, pain and regret. Gurbani reminds us that pain and pleasure are like two robes hanging in the wardrobe, robes that each of us must wear in turn. No one is exempt. It follows, then, that the measure of a person is in wearing the robe of suffering with dignity, nobility, grace and calm good humor. This is how charhdi kalaa is defined. Charhdi kalaa then becomes a state of mind. It does not derive its life from the size of the bank account, Armani suits in the closet, a fleet of Porsches or even looks that can launch a thousand ships. Instead, it springs from and is defined by a life of hope and faith. There can be no charhdi kalaa without faith in bhana and hukum. God does not burden us with more than we can handle. When this principle becomes integrated into our existence and consciousness, it transforms ordinary living into a life of faith. Charhdi kalaa asks a Sikh to feel and to know that God and Guru are always within you, beside you and around you. Think of the well-known prayer often ascribed to Plato: “God, grant me the power to change the things I can, the serenity to accept what I cannot change and the wisdom to know the difference.” In this prayer, asking for serenity speaks powerfully of bhana and its acceptance. The fact that it is a prayer illustrates the reality that everything exists and occurs within hukum, or a certain order, even if and especially if it remains misunderstood by us or beyond our understanding. Keep in mind also the first part of the prayer that speaks of self-effort. Hukum in Sikh parlance is a concept not so easily grasped. Literally translated it would mean “order,” but “order” in the English language has at least two connotations. It means both a command from higher authority and an organized system with its immutable laws of cause and effect, as opposed to random events. The Sikh term hukum, too, as Hew McLeod points out, embraces both concepts and meanings. Bhana speaks of willing and graceful acceptance of reality. These two — hukum and bhana — are thus inseparably intertwined. The latter does not and cannot exist without an understanding and acceptance of the former. But bhana decidedly is not fatalism. Sikhism teaches a message of active participation in life in which the best prayer is honest self-effort. When such efforts are accompanied with an attitude of faith, the results, no matter what, will be accepted with grace — that is the meaning of accepting and internalizing bhana and hukum. People living with bhana and hukum as their driving forces live in charhdi kalaa; such lives can work miracles and attain the impossible. Without these concepts at the axle of one’s life, there can be no equipoise, no centered existence, no sehaj. Without them one cannot be at the mountaintop nor plumb the depths of the valley of sorrows. It isn’t charhdi kalaa if it is found only in victory, never in defeat. This way guarantees more suffering. Charhdi kalaa is easy in victory, even inevitable. It is in defeat that it must be sought, cultivated, nurtured and harnessed. It is in the depths that charhdi kalaa defines character. And that is the essence of Sikh teaching. At one time in my life I was working at night and going to graduate school during the day. Life was hard. My research advisor and I often talked about all kinds of things, including Sikhs and Sikhism. Even though he was not a Sikh, we also talked about the Sikh teaching on charhdi kalaa and how difficult it was to always walk the path. One day after thinking awhile he said he understood and then summarized the concept in one simple sentence: When life gives you a lemon, make lemonade. I.J. Singh |

This little essay is going to be one of clichés, but, I hope, not without meaning. A string of words aptly joined becomes a cliché through overuse; it becomes overused because nothing else carries the truth quite so simply, precisely or effectively. Phrases become clichés because they contain a kernel of truth. Often the lesson is right there on the surface; clichés are both efficient and efficacious in delivering it.

This little essay is going to be one of clichés, but, I hope, not without meaning. A string of words aptly joined becomes a cliché through overuse; it becomes overused because nothing else carries the truth quite so simply, precisely or effectively. Phrases become clichés because they contain a kernel of truth. Often the lesson is right there on the surface; clichés are both efficient and efficacious in delivering it.