|

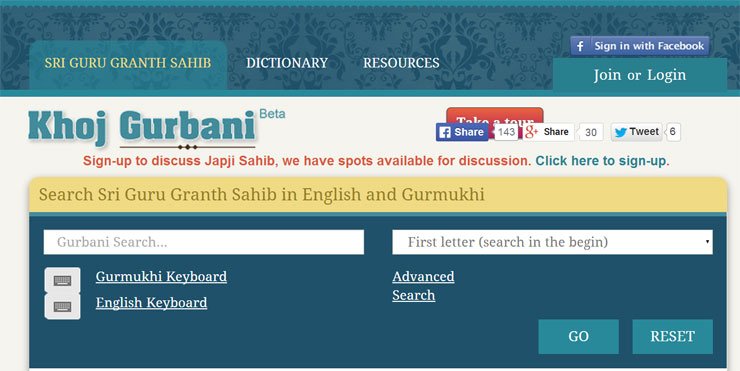

CELEBRATING KHOJ GURBANI: Pitfalls & Pleasures of Translating I.J. Singh [email protected] The Internet is abuzz these days with a sea of initiatives in translating the Guru Granth. I hope to capture some of the complexity of this never ending task today. In the process I want to take note of a new portal Khoj Gurbani– an effort embarked upon by mostly young tech savvy minds; I am the lone exception on both counts, Khoj Gurbani was unveiled last week on Vaisakhi 2014. A group of Sikhs: men and women, based around the world in India and the diaspora aim to meet via a connected, wired platform once a week. Starting from page one of the Guru Granth, and moderated in turn by one of the small group, the participants, who can log in from the world over, will raise questions and exchange insights and ideas on how to translate the verses being read, how to frame the ideas of the weekly reading assignment in user friendly terms and how to present the proceedings in easily searched and researched platform. I, of course, celebrate the initiative most heartily. I also see that in a single hour the group would be sorely limited in how much material from the Guru Granth it can pursue – perhaps no more than a page or two. Clearly reaching the last line (page 1430) would take us far into the foreseeable future; it would surely be a lifetime project. On the other hand, one could argue that several English translations and search engines of the complete Guru Granth already exist; I possess four of them. Some are easily accessible on the computer with appropriate search engines. Do we need another time consuming initiative. My answer is an unequivocal yes. So, let me build a meandering and convoluted case for it. Today, there is perhaps no continent or country where Sikhs are not. Wherever we have ventured, we have taken our lifestyle, family values, seductive cuisine, song and dance, and our incomparably enterprising spirit. And we have taken along Sikhi – a unique, universal and timeless message -- a way of life that makes us what we are. Now we have a globally connected existence of a nation without walls.

Historically ours has always been a polyglot reality, but now more than ever. Now Sikhs are growing up outside the comfortable cultural cocoon of Punjab and India. Their norma loquendi is no longer Punjabi or any Indic language; the cultural context, too, has dramatically shifted. The mythological antecedents of India shaped many of us, not because they were essential to core values of Sikhi, but because Indian mythology was the overarching cultural context of India. This lore is now alien to a new generation of Sikhs. Many diaspora Sikhs may be more conversant with Greek folktales than with the Indian. This is not unexpected or unwelcome; technology merely hastens the process. Much as any immigrants, Sikhs in the diaspora remain in an increasingly complex bind. We dearly value, what is for us many of us our mother tongue, Punjabi, but within our lifespan it has already diminished to a transactional presence, effectively limited to social banter, music and humor. We are not comfortable enough to pick up a book of poetry, history or philosophy in it, and so we usually don’t. Then there is English, but in that, too, our command of the language is frequently transactional. We master it to the extent demanded by our work that puts food on the table, but rarely, if at all, for the pleasure of ideas on history, poetry or philosophy in it. So, the education of the mind is often effectively stalled in both Punjabi and English. Now consider this: The repository of our spiritual heritage -- Guru Granth – is traditionally penned in the Gurmukhi (Punjabi) script, but contains little of present-day conversational Punjabi vocabulary. In fact, Gurbani showcases the lexicon of many Indic and Middle Eastern languages extant when it was composed 300 to 500 years ago. It is written in the vernacular of the times with copious references to Indian mythology. Gurbani does not endorse mythic legends but frames the teaching such that it would resonate with the average Indian of that time. Why? Clearly, no matter the topic, teaching is best couched in the culture, context and language of the student or else the lesson is lost. I can vouch for this, having taught a very different discipline for umpteen years in the North American university setting. Most Sikhs in India, but even more, those who have spent lives outside it, are not quite so adept in the Indian languages, and absolutely at sea in much of Indian mythology. Plus, those legends have little or no relevance to our present day lives. In brief, I submit that many of us are equipped to handle neither any Indian language nor English with much finesse or fluency beyond a rudimentary transactional level. We are equipped to peruse history, philosophy or poetry in neither English nor Punjabi. And the mythology only distracts us. Hence, the dire need for translations; they connect us to the eternal and essential message of Gurbani without disconnecting us from the modern world in which we live. Moreover, our sacred writings are largely cast in inspired poetry that, to us, is divine. And I don’t need to tell you the difficulty in deciphering the mind of a poet when he plays with words, language and meter in the cause of poesy. Ergo, good faith efforts to translate the poetry of Guru Granth and capture its lofty message are critically essential; how else can we understand or adopt it as a blueprint for our life? Why translate? Think of a moment in any conversation, no matter how simple, no matter if it is with an arch enemy or a soul mate. Isn’t it accompanied by some thought about what the other person really meant or understood? Isn’t that, in effect, a translation of the simplest communication? Understanding the other person demands tuning into (translating) his or her moods, gestures, body language, words and frame of reference and mining them for meaning. Translation then is the only effective way to delve into what another mind has to offer. War and peace stem from translating or mis-translating each other before framing responses. I aim today to plough a path between the pitfalls and rewards, the bouquets and the brickbats whenever we dive into translation. The literary output of human civilizations of yore often comes to us via translations. That’s how we know of Homer, the greatest poet of ancient Greece, and of Virgil and Ovid, of similar standing in Rome of a bygone era. We celebrate Kalidasa as the preeminent playwright and poet of ancient India and we access his work through modern translations of it. Since a translation and the original text can never be equal to one another, translation is, by definition, an essentially impossible task. So the relevant question becomes: how accurately does a translation capture the mind and insights, even the beauty of the poet’s meter and language? Such questions are rarely laid to rest, but they give birth to new scholars of the original language and also the one in which a translation is done. Countless academicians earn doctoral degrees from such effort. By starting from every translator’s premise: “I am going to attempt the impossible,” there is an essential courage implied by taking on the task. Times and cultures change, as do languages. Over time, the vernacular becomes opaque, literary language even more so. For instance today, only a few hundred years after Chaucer, his Canterbury Tales defy comprehension without translation into modern English. Similar hurdles abound in engaging with classics of Western civilization, such as the writings of Plato, or German and Latin Masters. How good is any translation? This is not so easily answered, but it deserves an exploration. As examples, let’s revisit two classics: the poetry of Omar Khayyam and the King James New Testament. And then we will segue into the matter of translation of Guru Granth. Omar Khayyam was a Persian poet and astronomer who lived from around 1048 to 1131. Some of his quatrains (Rubaiyat) have seen at least 15 translations in English and also in German, French and even Indic languages, including Hindi and Bangla. Why so many English versions? Obviously, scholars differed on fidelity or its lack in the available renderings. In fact, some critics derisively labeled the immensely popular version by Edward FitzGerald as the "The Rubaiyat of FitzOmar." FitzGerald himself published five editions in 30 years that show significant variations among them. A translation depends on how the translator interprets the philosophy and context of the original message. My second example, even more instructive, comes from Christianity. Many versions of the New Testament exist. The earliest was in the Koine Greek language; some chapters were possibly in Aramaic. Some Hebraic scholars deem the label “New”Testament to be a misnomer open to misinterpretation; they reason that “Christian Bible” would be a more accurate title. The first English translation of the Christian Bible was by followers of John Wycliffe but it was banned in 1409. King Henry VIII authorized an English translation, The Great Bible; its version (The Bishop’s Bible) followed in 1568. The puritans, a part of the Church of England, were upset by these versions. In 1604, King James convened the Hampton Court Conference. It proposed a new translation that became the Authorized Version of the Bible in English, and was prepared between 1604 and 1611by 47 scholars, all members of the Church of England. Opposition to this Bible surfaced early. Hugh Broughton, a Hebraist scholar, condemned it in 1611; Broughton said that “he would rather be torn in pieces by wild horses than that this abominable translation should ever be foisted upon the English people." But a hundred years later, it became the Bible in all Anglican and Protestant denominations and remains unchallenged today. Nevertheless, The Roman Catholic Church continues to follow its own Bible that has seven more books than the King James Version. The history of scriptures in most religions is equally convoluted, except that the Guru Granth Sahib of the Sikhs was compiled by the Founder-Gurus themselves and its authenticity remains unchallenged. My purpose is not to judge any scripture but to explore problems inherent in translation and transmission of a heritage. A plethora of Sikh sites on the Internet host translation projects these days; I welcome them and I also wonder. When my interest in the Guru Granth awakened, my intimacy with its language and grammar was minimal. My stumbling eased when I discovered the 1966 UNESCO publication -- an English translation of selections from Guru Granth and related writings by five iconic masters of the grammar and lexicon of Sikh scriptures – Trilochan Singh, Jodh Singh, Kapur Singh, Bawa Harkishen Singh and Khushwant Singh, and edited by a poet, George Fraser. I still find this by far the best translation, way above any that I have seen. It captures the magic, even though now the language seems a little archaic, and the book remains incomplete. In the early 1970’s the first complete translation of Guru Granth in English by Manmohan Singh appeared. (Ernst Trump’s translation was way earlier, but it was incomplete.) Manmohan Singh’s phraseology was often awkward; sometimes he left me wondering exactly what he meant. As translations by Gopal Singh, Trilochan Singh, Sant Singh Khalsa, Pritam Singh Chahil, and Kartar Singh Duggal appeared I eagerly pounced on them, but was left flailing at sea by the language, style or lack of clarity. In time, I graduated to exegesis in Punjabi by Bhai Vir Singh, Professor Sahib Singh or others. Sometimes they, too, left me untouched and baffled when they appeared to mix unquestioned traditional or mythological lore with the pristine purity of the Guru’s message. All our existing translations bar two are solo efforts – one person’s endeavor. The exceptions are the UNICEF publication and the four-volume Shabdarth in Punjabi which is not a complete translation, but a guide to difficult words and concepts throughout the Guru Granth; it is published by the SGPC and no single author is identified. Of many that are possible, I offer you brief examples where the traditional translations often leave me stranded. Should one literally interpret Farid’s recommendation to kiss the feet of the enemy? Or, for that matter, what to make of the traditional take on the cycle of birth and death; or that even our smallest action is controlled and prewritten by God, which would then leave us no free will and no option to act otherwise. I don’t quite see that a Creator -- that Gurbani assures us repeatedly cannot be measured, has no form, shape, color, caste or gender -- sits out there somewhere micromanaging my puny existence, keeping track of all my sins committed or contemplated, and yet all of my actions are in accord with God’s prewritten dossier on me. Such matters often leave one wondering what exactly the Guru meant. As I see it, living a life in Hukum, like walking in the shadow of God, transcends our literal rendering of Gurbani. To me it becomes to live in the present – in the moment – to have the courage to change the things we can change, to accept with serenity (as Hukum) what we cannot change, and the wisdom to know the difference. After all Gurbani is mystical poetry – full of allegories, analogies and metaphors, seldom to be literally rendered. Ultimately, the follower of a faith has to interpret what the teaching and the doctrine or traditions mean to him or her. A translator’s lot is never easy. He has to know two cultures intimately: their languages, idioms and traditions, the land and the people, the history and mythology that have shaped them. And then the translator has to navigate between the two realities seamlessly. In the process of translation an early obvious loss is the inability to capture the rhythmic flow and cadence of inspired poetry that transcends the literal rendition. Given the richness of the original language, grammar and mythology, any translation project promises to be a life-long unfinished quest. Remember that a translator needs to merge the cold-blooded mind of an analyst and grammarian with the warm joyous heart of a poet in an existence of faith. Not only that, but the translator himself is growing and changing and therefore his insights into the original text are bound to change over time. Any translation is but a snapshot in the moment of committing pen to paper. Translation is a daunting task but surely, many dedicated translators who are steeped in Sikhi will come out of making the effort to translate. Even when the language is not so alien or abstruse, differences in interpretation between equally brilliant minds are not uncommon. Look at the laws of any country. Without plausible and differing interpretations of the same law a society would not need thousands of lawyers and so many different levels of judiciary, and the courts would never be so busy ferreting out the truth. For example: What exactly did the framers of our Constitution really mean – Is ours a Christian nation? How is the line between Church and State to be interpreted? Do differences in interpretation of civil rights exist or don’t they? And many more questions like these. This says to me that I, or any Sikh, will always have to struggle to make sense, from an inadequate translation, of what the Guru likely meant, no matter how good it appears to be. And that becomes the lifelong path of a Sikh. Do I still get lost? Often! But I am reassured by Gurbani that my smallest, hesitant step towards the Guru will be reciprocated by the Guru covering miles towards me. In other words, grace will pervade and prevail. And that with further analysis, cogitation and reading, a sense of the poetry will emerge. When I realized this, I knew that I was on my way home. I love all translations; particularly the ones that don’t seem so good or easy. Essentially, they place the onus on me. I then stop and wonder if the Guru could have meant what the translator implies. If the translations had been excellent, I might never have made the struggle my own. No person and no interpretation may be guaranteed to be totally true today and forever. The best scholar or translator, like a lawyer, can only guarantee honesty of effort, not purity of result. That and a hefty dose of grace make my relationship with the Guru Granth semipiternal. Guru Granth tells us (p. 594) “Dithay mukt na hoveyee jichhar sabd na karay vichhaar,” it is not the sight of the Guru Granth but thoughtful engagement with the Word that will liberate one. The translations are necessary and the road ahead is rocky. I celebrate Khoj Gurbani and point out that what we translate today is not for ever; it will need retranslating and tweaking by every new generation. Explore the translations, old and new, and keep on hand the original text of Gurbani. Access the site by clicking on: www.khojgurbani.org April 28, 2014 |