One of the most iconic symbols of Ranjit Singh’s kingdom is the golden throne, now safely housed in London’s V&A museum. It is on permanent display on the museum and arguably is one of their most important objects. Over the next few months the Golden Throne will form part of the dazzling Maharaja exhibition that runs from October to December and will ultimately tour to Germany and Canada.

One of the most iconic symbols of Ranjit Singh’s kingdom is the golden throne, now safely housed in London’s V&A museum. It is on permanent display on the museum and arguably is one of their most important objects. Over the next few months the Golden Throne will form part of the dazzling Maharaja exhibition that runs from October to December and will ultimately tour to Germany and Canada.

I was given the very rare privilege of examining the throne close up, outside of its normal glass case a few weeks ago. I would like to share some of the pictures (by Jasprit Singh) and some of its history here, on Punjab Heritage News: Seeing the throne close-up is a real pleasure, the fact that it is in existence at all is a miracle. Few other communities as young as the Sikhs have lost so much of their material heritage and whilst Britain today (most notably the V&A) does a world-class job in preserving Sikh heritage our country’s predecessors were not quite so benevolent.

Seeing the throne close-up is a real pleasure, the fact that it is in existence at all is a miracle. Few other communities as young as the Sikhs have lost so much of their material heritage and whilst Britain today (most notably the V&A) does a world-class job in preserving Sikh heritage our country’s predecessors were not quite so benevolent.

When the Toshkhana was raided following the annexation of the Punjab in 1849, the East India Company and its head Lord James Dalhousie were near bankruptcy. The royal treasury was a literal gold mine for them and they quickly saw a chance to mend the battered finances of the company.

Dalhousie had his secretary, Dr John Login, prepare detailed inventory of the contents of the toshkhana; Login was blinded by the riches within, commenting on the “vast quantities of gold, silver, the jewels not to be valued, so many and so rich! … and perhaps above all, the immense collection of magnificent Cashmere shawls, rooms full of them laid out on shelves, and heaped up in bales – it is not to be described”. This was not to be a careful listing of a rich artistic tradition or an attempt to carefully document a vastly important collection for the future. It was a catalogue for a fire sale. Over 9 heady days, Dalhousie auctioned off the vast bulk of the treasury. The larger bulkier items were problems; who would buy them Dalhousie questioned, a silver pavilion caused a particular problem – so he had it melted down. The Dalhousie auctions remain one of the most egregious acts of cultural malevolence in Sikh history.

This was not to be a careful listing of a rich artistic tradition or an attempt to carefully document a vastly important collection for the future. It was a catalogue for a fire sale. Over 9 heady days, Dalhousie auctioned off the vast bulk of the treasury. The larger bulkier items were problems; who would buy them Dalhousie questioned, a silver pavilion caused a particular problem – so he had it melted down. The Dalhousie auctions remain one of the most egregious acts of cultural malevolence in Sikh history.

Not so for the throne of Ranjit Singh – a remarkable and unique item that stood out from the multitudes of plump jewels and crafted weapons. Dalhousie initially attempted to keep the throne for himself and reported to the British Government that: ‘It is set apart as an object which the court would probably desire to preserve, but as it is bulky, I shall not forward it until I receive orders to do so’. The government saw through his ruse and demanded it be sent to London with the other treasures that were deemed too precious to be auctioned (including the Koh-i-noor) but not before Dalhousie commissioned a replica of the throne carved in wood for his own collection. The Golden Throne was made for Maharaja Ranjit Singh by a Muslim goldsmith, Hafez Muhammad Multani, between about 1820 and 1830. The craftsman decorated thick sheets of pure gold with a design of flowering plants that cover the wooden core of the throne.

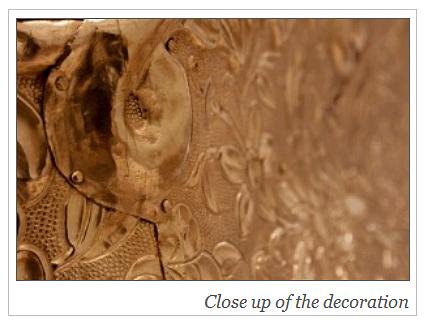

The Golden Throne was made for Maharaja Ranjit Singh by a Muslim goldsmith, Hafez Muhammad Multani, between about 1820 and 1830. The craftsman decorated thick sheets of pure gold with a design of flowering plants that cover the wooden core of the throne.

Hafez Muhammad must have been a leading goldsmith of the Lahore court as he is mentioned twice in the detailed inventories made of the treasury when the Panjab and Sikh crown property was annexed by the East India Company in 1849.

It was shipped to the Indian Museum in London. In 1879, Ranjit Singh’s Golden Throne moved to the South Kensington Museum, later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum.

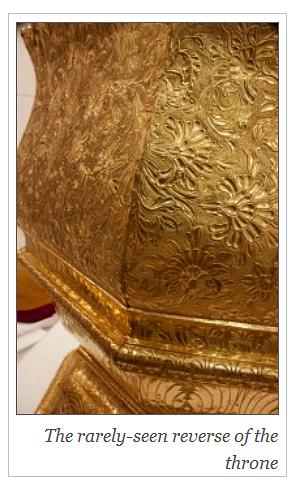

The throne is breathtaking in its execution. A wooden substructure is covered in deeply reliefed solid gold sheets; the decoration is rich and dripping with symbolism. The throne itself is in the form of an opening lotus flower – a metaphor regularly used in Sikh scripture where the Gurus enjoin Sikhs to live in the world as the lotus flower blooms in murky waters; to live in the world unaffected by the world’s attachments. The decoration repeats this motif around the base. Ranjit Singh, seated in this throne, during his public durbars would have been a glittering sight, at once both maharaja and religious figure. Close up, the detail of the throne is readily visible and even for someone like me, who has seen it countless times at the museum I was struck by the sheer opulence of the work on the back of the throne which is sadly barely visible in the current display case.

Close up, the detail of the throne is readily visible and even for someone like me, who has seen it countless times at the museum I was struck by the sheer opulence of the work on the back of the throne which is sadly barely visible in the current display case.

In preparation for the maharaja exhibition, the throne was in the conservation department for cleaning. This was being painstakingly carried out by the V&A’s head of metalwork conservation Diana Heath. I am always struck at the precision and professionalism of conservation experts and Diana’s work on the throne was just enough to clean ten years of light dust without attempting to interfere with the 200 years of patina that characterises the fold work – a sharp contrast to the disastrous and heavy handed re-gilding of the Harimandir Sahib in 1999.

I hope that when it returns from its exhibition and tour around the world as part of the Maharaja’s exhibition it is back on public display in a manner that will allow every visitor to experience the masterpiece that is Ranjit Singh’s Golden Throne.

(Photos by: Jasprit Singh)