LANGLEY, England (Reuters Life!) - A short drive away from Windsor Castle, a group of ferocious-looking, blue-turbanned men are trying to preserve a martial art that frightened the life out of the British when they ruled India.

LANGLEY, England (Reuters Life!) - A short drive away from Windsor Castle, a group of ferocious-looking, blue-turbanned men are trying to preserve a martial art that frightened the life out of the British when they ruled India.

Grunting at each other like wild boars, they brandish swords and sticks according to the dictates of the Sikh fighting discipline of Shastar Vidya.

Their teacher, Nidar Singh, believes he is the only master of the art seriously practicing today.

The 42-year old British-Indian barks out orders in a thick regional English accent to an attentive class of mainly Sikh pupils ranging in age from 5 to 45.

Singh is on a mission to keep the martial art alive and he spends all his time teaching in schools and community halls across the country.

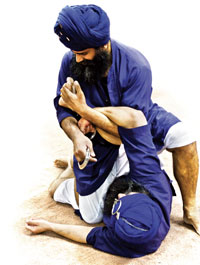

Razor-sharp swords flash through the air, wooden batons are brandished and hands grab the heads of opponents in threatening moves designed to kill in an instant.

With a long, dark beard and huge dark eyes peering out from his dark blue turban, Singh implored his students to "Watch, watch" as he mock-felled one pupil after another in a dizzying display of ferocity.

"It's a battlefield art, so the idea is if you can defeat the enemy by sheer intimidation then all the better ... the art is very aggressive," he said. "The idea is to traumatize the people watching."

The warrior art of Shastar Vidya (weapon science) once practiced by Sikhs in the Punjab, was banned by the ruling British, who were intimidated by the success, bravery and sheer aggression of the martial art. The blue turbans were forbidden and only a ceremonial form of the art was allowed in the Raj. The closely guarded secrets of the true form went underground.

Nidar Singh fears that unless he passes on his knowledge, learnt from a now-deceased previous master in India, the art form could be extinct in a few decades. He says Shastar Vidya also has practical uses in the modern world.

"On the one hand we are preserving heritage and traditions, on the other hand we are getting physically fit and mentally alert and learning self-defense as well," he said.

Younger students are not given the wooden sticks. They only learn defensive moves to help protect themselves rather than encouraging violence.

Nine-year-old Georgina Kelly said she's already used her new-found skills to fend off a bully at school.

"I used one of the moves on her, I didn't hurt her and it helped me, so she doesn't bully me any more. It's really fun and I learn a lot."

Harkaram Sroa, also 11, practices fancy footwork and how to form his fists so they are fight-ready. He said the classes have given him confidence.

"It helped me with my self defense and things like that and so I just started coming more and more and now I really enjoy it," Sroa said.

For the older pupils, learning India's lost art of war gives them a link to their cultural heritage.

"It's given me the link back to my traditions and the way my ancestors thought and how they fought, but beyond that it gives me a perspective into the deeper philosophy behind Sikhi," said Harninder Sanher using the Punjabi word for Sikh tradition.

He said the fighting aspect of the art form is only a small part of what appeals to him.

"A deeper aspect for me is all the philosophy behind it and that gives me that depth and that rich history that I can't seem to get from anywhere else."

Ironically Nidar Singh was only able to research the art banned by the British in Britain.

The former colonial rulers obsessively kept safe all the books and manuscripts, which are now held in the British Museum in London. That has enabled the more dedicated pupils to study the philosophy behind Shastar Vidya.

"It's all contextualized with ancient mythologies of India -- even as a British-born Asian I wasn't very familiar with those, so that's something I actually had to go away and do," said Gurpreet Dhillow.

Shastar Vidya has existed in the subcontinent for thousands of years, long before Sikhism emerged in the mid-16th century. Singh regards it as an art form that has been looked after by many different creeds and cultures. He sees the Sikhs as the latest custodians of the art.

He is passionate about preserving it for future generations.

"The last thing I want to do, under my watch now, is for it to go extinct. The grand master who taught me had the same desire. As an ancient art it enshrines a lot of wisdom and knowledge of the past masters, things which we will get nowhere else and it would be sad for us to now lose it all," he said.

Singh has recently established classes in Berlin and in America and plans to expand further around the world to ensure Shastar Vidya lives proud once again.

(Editing by Paul Casciato and Steve Addison)