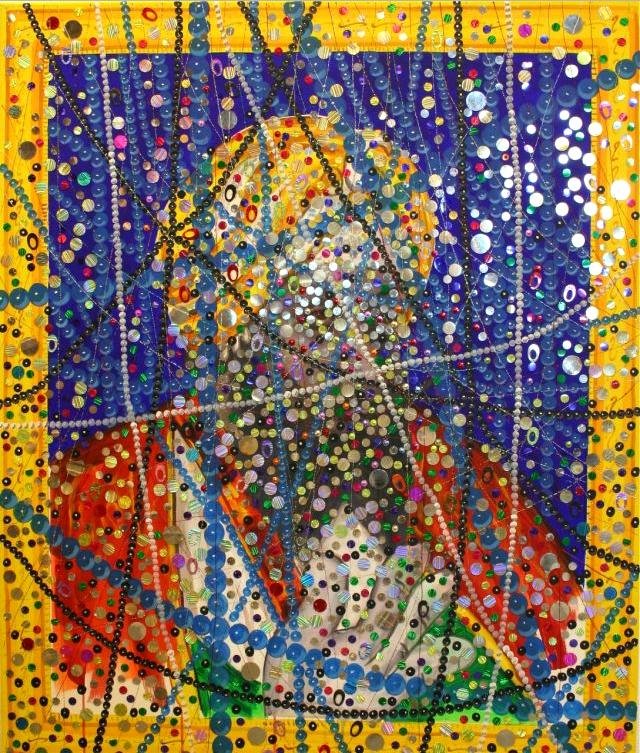

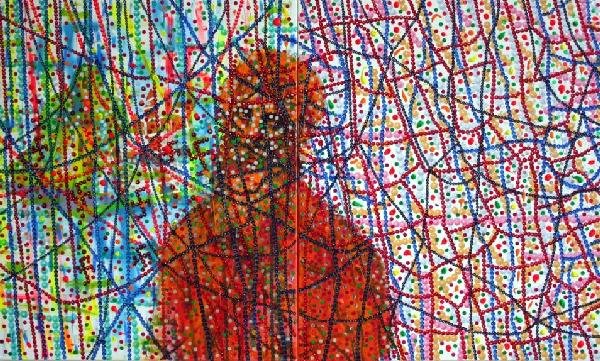

Nirmal Singh Dhunsi’s spicy paintings call forth both sweet tastes and an intensely burning sensation on the tongue. He makes them rapidly, mixing ingredients from East and West and from the entire art history. Spangles, glitter glue and painted strings of pearls decorate and cover the canvas surface.

Below this surface one finds content of private and religious character as well as content related to current affairs. Figurative and non-figurative layers overlap and make up an aesthetics that is deep and extravagant at the same time.

Lately Nirmal has worked with painting, sometimes exploring various detours from the road he has decided to travel: the one he defines as his masala way. His present images are even more luxuriant and exuberant than his previous works. At the same time they represent a true challenge to the spectator who finds himself in the double role of merrymaker and archaeologist: beneath the glitter and the strings of pearls there are yet more layers to discover.

Excavations reveal findings related to the artist’s past as a professional painter of miniatures and posters, his present situation as a respected visual artist in Norway – as well as anything that may happen to exist between these co-ordinates. Which is certainly not negligible. The masala paintings are characterized by art historical and trans-cultural references and yet they have a unique, recognizable quality. This quality is a result of Nirmal’s numerous voyages between two very different parts of the world and a well-developed ability to soak up visual impressions. He is more than commonly concerned with what goes on at the international art scene at large. If you blend history and topicality, external influences and a personal sense of style, what you get is Nirmal’s art.

The Observer

The Masala paintings can thus be regarded as the artist’s blissful mixtures of ‘spices’, the way he sees himself and the world just now. He could not have painted these paintings three years ago, nor can he paint these images in three years time. Something that preoccupies him greatly at the moment is the increasing globalization and changes that take place either incredibly slowly or surprisingly rapidly. The past tied up in the present, the future suddenly appearing here and now: plastic bags with the logo of the food chain Rema 1000 laid at the feet of the gods Shiva and Ganesha. Nirmal Singh Dhunsi is an observer. Taking advantage of his double identity he may, more or less like an anthropologist, study both Norwegian and Indian culture from the position of an outsider. When the distance between the various parts of the world diminishes and the flow of people and merchandise increases, it is called cultural ‘entropy’. New combinations emerge, borders are wiped out and new ones appear. Globalisation is not a state of being; it is a process.

Nirmal’s family belongs to Sikhism, a religion that emerged in the Indian province Punjab about 500 years ago. The art of the Sikhs has traditionally been a combination of many different styles, with an open-minded, welcoming attitude to foreign influences. Even though Sikhs and Hindus are significantly different when it comes to culture and religious beliefs, the two groups live peacefully side by side. The two cultures borrow elements from each other’s religion, and Nirmal Singh Dhunsi’s masala paintings is best understood in the light of this generous and humble mentality. And yet the artist himself is critical and inquisitive in relationship to the phenomena that he allows to stimulate his work.

The aesthetics of sumptuousness that characterizes the masala series, is inspired by (and comments on) the Hindus’ interminable adorning of their gods. The idols of the Hindus are not representations of the gods; apparently they are the gods: they need food, care and thoughtful consideration, and they are flattered by gifts of tinsel and pearls. In the Hindu society, to cover up is a deeply rooted attitude. When the idols are eventually worn out, they are placed in glass cases, and the decorating continues on the glass surfaces. The phenomenon is both historical and psychological; one does not know why one performs these rites, but they must be upheld. As an artist, however, Nirmal Singh Dhunsi still asks why, as is the case with the Indian-British artist Anish Kapoor. The question is the same, but Kapoor, with his heaps of finely grounded colour pigments, has chosen a different approach. While most Norwegians find nature at its most compelling when it bears no traces of human intervention, Indians adorn trees by painting them in vibrant colours. Such cultural traditions and habits are presented in an uncommon perspective and may thus be interpreted in new ways. Both Dhunsi and Kapoor take materials used for covering up and adornment out of their customary contexts, shifting the focus from what is covered up to the materials employed.

A similar change of focus took place in Western art on the verge of Modernism, when painters like Edouard Manet defined the physical presence of the paint on the canvas as the main point of the artwork. What was depicted became subordinated to the manner of depiction; painting qua painting was on its way to autonomy. When Nirmal covers his canvases with strings of pearls, he alternates between using them as ‘adornments’ to his motifs and making them into motifs in their own right. As a third alternative he employs them as abstract visual elements, as row upon row of colour patches. A highly art-historically conscious contemporary artist, he playfully juggles with various levels of representation.

Spangles Colour Scheme

When facing one of Nirmal Singh Dhunsi’s paintings the spectator has several choices including the option of alternating between focusing on the surface and paying attention to the earliest layers of paint. If the eye stops at the surface, a spotty play of colours will sometimes remind you of Whistler’s or Klimt’s golden and forest-green nuances. In other works, bright neon colours point back to pop art.

When it comes to dealing with the surface, Nirmal alternates between making use of pointillism and more geometrical op art. The attached spangles glitter, adding a striking play of reflections. The strings of pearls that divide the surface into sections may also be seen in connection with the modernist grid tradition, but merely as a comment from the wings. For under the autonomous lines and independent, unbroken colours there are portraits and brief stories to be found. This is where the festivity partly enters a zone of gravity. If you let your eyes wander towards the very earliest layers of acrylic, your gaze will meet that of the artist’s two sons, his father, Eugene Obiora, and religious masters. Their faces express authority, melancholy, discomfort, concentration. Those who are historically insignificant are brought to our attention, the physical and the banal is exalted to holiness. Actually, the choice of colours is linked to the artist’s ranking of the motifs, constituting a kind of reversed cast system. It is in these layers that we find Nirmal’s riddles, covered up and shrouded in mysterious veils. Evidently, he does not intend to divulge much, but if we invent the answers ourselves each one will find the suitable ones. First and foremost, it is a matter of taking one’s time; if we do, we will certainly find helpful hints.

Every picture is autonomous, but put together with others it will achieve a new stature and significance. Stories emerge when the paintings are presented together and the resulting conversations are both of the planned and the coincidental kind. To Nirmal, the whole exhibition is one great work. Sometimes it will take hours of trying out alternative mountings to achieve exactly what he wants (or what the images want.) When you look at it that way, a collection of ten paintings may contain an unexpectedly large number of possible artworks. To find the optimal solutions the artist makes sure to take both formal aspects and the content of the image dialogues into consideration.

Cardamom, Coriander and Cinnamon

In every single painting the acrylic colour is used directly from the tube; on the canvas fluorescent colours are combined with unbroken primary colours. The effect is striking and sumptuous, in keeping with a Bollywood universe where ‘less is a bore’. Bollywood films, a part of Indian film industry which lately is also produced in England, are typically musicals with an exaggeratedly melodramatic plot. Apparently, there are no limits when it comes to use of colours, flashy effects and ornamentation; and when you think they are singing the chorus for the last time, you will discover that there are still five more verses to go and another dozen of dancing actors suddenly make their entrance. The starring actress is the one with most diamonds and the longest hair, carrying layer upon layer of feather light silken fabrics. The films flirtingly balance between the innocent and the vulgar and they aim at staying superficial. In this sense, Nirmal Singh Dhunsi’s universe is something radically different, but it shares the playful and humorous aesthetics of the Bollywood films. Another common trait is the blending of styles and genres: Bollywood will often be a mixture of comedy, action film and the romantic kind and is appropriately named masala film.

Nirmal remains true to his chosen course and plans to paint at least 100 ‘maximalist’ masala paintings. That is the only way of getting them under the skin. You will not be a great cook until you can make your specialities blindfolded, nor will you be a true guru until you know yourself. The artist will never get a complete overview of the state of the world, but he may explore parts of it and share his insights with the viewer. A combination of Eastern holism and Western individualism can be traced in Nirmal Singh Dhunsi’s ‘garam masala’. In a good mixture of spices the tastes are harmonious but still distinguishable. The cinnamon is sweetish, supplementing the taste of pepper; the coriander rounds it all off. The paintings are like spices for the eyes and the mind and the aftertaste lingers on uncommonly long.

Garam Masala

1 1/2 teaspoon of whole pepper

4 tablespoons of whole coriander

2 teaspoons of caraway seeds

10-12 whole, large cardamom seeds (brown)

6-8 tacks (cloves)

1 cinnamon stick

Grind mixture to a powder.