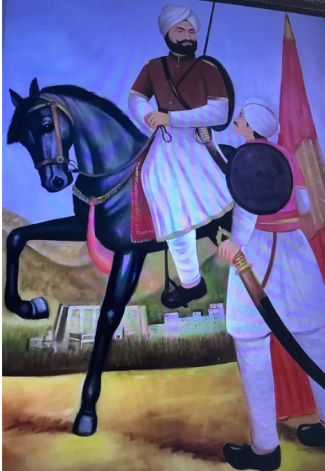

General Zorawar Singh, a celebrated commander of the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, played a pivotal role in the northern expansion of the empire. His military career is distinguished by his campaigns in Ladakh, Baltistan, and Tibet, which extended the empire’s reach into high-altitude territories of immense geopolitical significance.

Zorawar’s campaigns reflected unparalleled strategic vision and military resilience. In 1834, he successfully annexed Ladakh, overcoming geographical and climatic challenges. His subsequent expedition to Baltistan in 1840 further demonstrated his prowess, as he navigated the treacherous Karakoram range to subdue local rulers. However, it was his 1841 invasion of Western Tibet that solidified his reputation as a daring commander. Crossing the Pangong Tso Lake and reaching Mount Kailash and Mansarovar, Zorawar’s forces captured 550 miles of Tibetan territory within months.

General Zorawar Singh’s military career is closely intertwined with the expansion and consolidation of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Sikh Empire. Serving under Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, a vassal of the Sikh kingdom, Zorawar Singh played a pivotal role in extending the empire’s frontiers into the Himalayan territories, including Ladakh, Baltistan, and western Tibet. Appointed as a key military commander, Zorawar Singh was entrusted with the task of securing and expanding the northern territories. His disciplined leadership, innovative strategies, and ability to adapt to harsh terrain enabled him to annex vast and strategically vital regions, further cementing the Sikh empire’s dominance. His campaigns brought under control remote and challenging regions that had previously eluded centralized authority, demonstrating his unparalleled military prowess.

Zorawar Singh’s successes were instrumental in not only strengthening Raja Gulab Singh’s position within the Sikh Empire but also in bolstering the empire’s northern boundaries. His achievements earned him recognition and admiration as one of the most dynamic military leaders of his time. General Zorawar Singh’s life and achievements are intricately linked with the rise of the Sikh Kingdom under Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the Dogra dynasty of Jammu, led by Raja Gulab Singh. His military exploits, particularly in the challenging terrains of Ladakh, Baltistan, and Tibet, remain unparalleled in the annals of Indian history.

The Sikh Kingdom and Jammu Raj were shaped by the political upheavals following the decline of Mughal and Afghan rule in the 18th century. After the death of Maharaja Ranjit Dev of Jammu in 1782, the principality disintegrated due to internal strife and conflicts with the neighboring Sikh Misls, including the powerful Sukerchakia, led by Mahan Singh and later his son, Maharaja Ranjit Singh. These turbulent times saw frequent raids and territorial disputes, with the Jammu Raj losing its autonomy until it was annexed by the expanding Sikh Empire in 1812.

Ranjit Singh consolidated his power by subduing rival Sikh chiefs, defeating the Abdalis, and extending his kingdom from the Sutlej River in the east to the Indus in the west. By 1820, he granted Jammu and surrounding territories to Gulab Singh, who had risen through the ranks of the Sikh army, distinguishing himself in battles and administrative prowess. Gulab Singh’s ambitions and strategic acumen laid the foundation for the Dogra state, with General Zorawar Singh as a key architect of its military conquests.

Foundations of a Military Genius

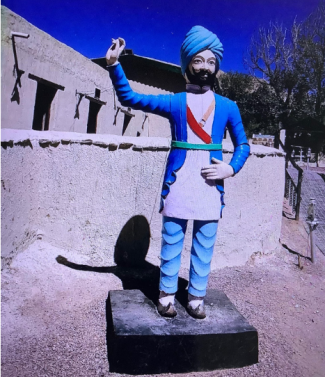

General Zorawar Singh, famed for his strategic brilliance and military conquests, was born in the late 18th century, likely in the Kangra region, into a Rajput family of modest means. Born in September 1784, he belonged to a Chandravanshi Kahluria Rajput family from Ansar village in Haripur tehsil of Kangra district. His father, Thakur Harji Singh, was likely a relative of the Raja of Kahlur. Harji Singh had three sons: Sardar Singh, the eldest; Zorawar Singh, the second; and Dalel Singh, the youngest. A family tradition preserved among the descendants of Thakur Sardar Singh, Zorawar Singh’s elder brother, recounts that Zorawar met his demise in Tibet at the age of 57 during the battle of December 1841. Based on this account, his birth year can be reasonably established as 1784. His upbringing in this rugged, martial terrain profoundly shaped his character, instilling a sense of resilience and a natural aptitude for military leadership. The sociopolitical context of the time, defined by the weakening hill principalities and the growing influence of the Sikh Empire, provided an environment ripe with opportunity for ambitious warriors.

Zorawar Singh’s early promise as a soldier attracted the attention of Raja Gulab Singh, the formidable Dogra leader serving under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. His appointment under Gulab Singh marked the beginning of a meteoric rise, driven by his loyalty, discipline, and strategic prowess. These early years in the volatile and faction-ridden landscape of Jammu prepared him for the challenges that awaited as a commander in the service of the Sikh kingdom.

The formative phase of Zorawar Singh’s career, spent in the service of Gulab Singh’s administration and military, was critical in honing his skills as a tactician and administrator. His early experiences in maintaining order and addressing rebellion in the Jammu region provided a foundation for the military achievements that would later define his legacy, including his celebrated campaigns in Ladakh and Tibet.

Mastery Over Ladakh: A Landmark Conquest

General Zorawar Singh’s conquest of Ladakh (1834–1835) stands as a remarkable feat in the annals of military history, showcasing his strategic acumen and ability to overcome formidable geographical and political challenges. Tasked by Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, Zorawar Singh embarked on this ambitious campaign to expand the Dogra dominion into the high-altitude regions of Ladakh, a Buddhist kingdom of considerable strategic importance due to its position on ancient trade routes and its proximity to Tibet.

The campaign began with meticulous planning, as Zorawar Singh gathered a well-equipped force of approximately 5,000 soldiers, comprising Dogra troops, Pahari recruits, and Ladakhi irregulars. The challenging terrain of the Himalayas, characterized by treacherous passes and extreme weather, was a significant obstacle, but Zorawar’s leadership ensured the army’s steady progress. His forces advanced through Kishtwar and crossed the Zanskar region, taking advantage of the element of surprise to swiftly defeat local Ladakhi forces. Zorawar Singh demonstrated not only military might but also political astuteness in consolidating his victories. He respected local customs, reinstated traditional governance under Dogra supervision, and levied taxes to secure revenue for Jammu. His decisive victory at the Battle of Sanko sealed the conquest, compelling Ladakhi rulers to accept Dogra suzerainty. By 1835, Ladakh was integrated into the Dogra kingdom, with a garrison established to maintain control.

This conquest significantly enhanced the territorial extent of the Sikh Empire, of which the Dogra kingdom was a vassal state, and demonstrated Zorawar Singh’s capacity to conduct high-altitude warfare. His success laid the groundwork for subsequent campaigns into Baltistan and Tibet, earning him the sobriquet “Napoleon of the East” for his audacity and military genius.

The Strategic Victory in Baltistan

General Zorawar Singh’s Balti campaign (1839–1840) marked a pivotal episode in the expansion of the Dogra Kingdom, showcasing his military brilliance and determination to consolidate control over the Himalayan regions. Baltistan, a predominantly Shia Muslim territory governed by semi-autonomous rulers, had long maintained its independence. The strategic significance of Baltistan, located on the trade routes connecting Ladakh to Central Asia, made it a key target for Dogra territorial ambitions under Raja Gulab Singh.

Zorawar Singh launched his campaign in 1839, advancing into Baltistan through the rugged and snow-laden mountain passes of Ladakh. The campaign was fraught with challenges, including extreme weather conditions and resistance from the local rulers. Undeterred, Zorawar Singh employed a combination of military force and diplomatic negotiation. His army, composed of Dogra regulars and Ladakhi levies, overwhelmed the scattered forces of the Balti chiefs.

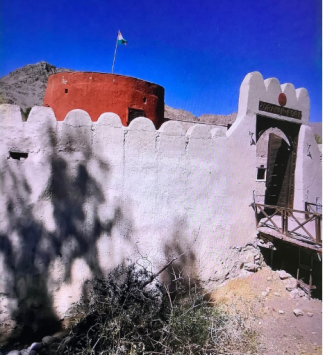

The campaign’s most significant battle occurred near Skardu, the stronghold of the region. Despite fierce resistance from Balti forces under the leadership of Raja Ahmed Shah, Zorawar Singh’s superior strategy and relentless pursuit led to the eventual capitulation of the Balti rulers. Skardu was captured, and the Dogra forces imposed their authority, compelling local rulers to accept Dogra suzerainty and pay tribute.Zorawar Singh’s success in Baltistan not only expanded the Dogra Kingdom’s territory but also established a direct link between Ladakh and the Gilgit-Baltistan region, further solidifying Dogra control over the western Himalayas. His effective governance in the newly conquered territories, marked by respect for local traditions and administrative reforms, ensured stability and long-term integration into the Dogra polity. The Balti campaign underscored Zorawar Singh’s ability to adapt to diverse environments and maintain discipline among his troops, solidifying his reputation as one of the most accomplished military leaders of the 19th century.

Expansion into Tibetan Territories

General Zorawar Singh’s campaign into the Tibetan plateau (1841) remains a landmark in the annals of Himalayan military history. This audacious expedition was an extension of the Dogra Kingdom’s policy of territorial expansion under Raja Gulab Singh, aimed at consolidating its dominance over trans-Himalayan regions. The campaign not only tested the strategic and logistical acumen of Zorawar Singh but also underscored the complexities of operating in a harsh, high-altitude environment.

Following his successful conquests of Ladakh and Baltistan, Zorawar Singh turned his attention towards the territories of western Tibet. This move was motivated by strategic considerations, such as securing trade routes and countering Tibetan claims over Ladakh. Zorawar Singh led a well-prepared force comprising seasoned Dogra soldiers, Ladakhi auxiliaries, and Gurkha recruits. The army traversed treacherous mountain passes, including the challenging Demchok route, to enter the Changthang plateau of Tibet.

The initial stages of the campaign were marked by rapid success. Zorawar Singh captured key Tibetan fortresses, including Gartok and Taklakot, effectively extending Dogra control over the region. His army encountered resistance from Tibetan forces and local chieftains, but his strategic brilliance and superior battlefield tactics enabled decisive victories. Tibetan troops, unaccustomed to organized warfare at such altitudes, were often outmaneuvered and overwhelmed. By late 1841, Zorawar Singh had penetrated deep into western Tibet, consolidating control over significant portions of the Ngari region. However, the onset of winter proved to be a formidable adversary. Severe weather conditions, coupled with logistical challenges, strained the Dogra forces. Tibetan forces, reinforced by the Qing Empire, mounted a counteroffensive. In the decisive battle near Taklakot in December 1841, Zorawar Singh fell in combat, and his army was defeated.

While the campaign ultimately ended in a Tibetan victory, Zorawar Singh’s conquest of Tibetan regions remains a testament to his unparalleled military leadership. His foray into the Tibetan plateau highlighted the geopolitical stakes of the region, setting the stage for future interactions between Dogra rulers, Tibet, and the Qing Empire.

Heroism and Sacrifice in the Final Campaign

The final chapter of General Zorawar Singh’s illustrious military career unfolded during his ambitious expedition into western Tibet in 1841. This campaign, undertaken at the behest of Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, marked the zenith of his conquests but also culminated in his tragic demise. The campaign was driven by a desire to consolidate Dogra territorial gains, secure vital trade routes, and extend dominion into strategically significant Tibetan regions.

In the months following his successful conquests in Ladakh and Baltistan, Zorawar Singh assembled a formidable force composed of Dogra infantry, Ladakhi auxiliaries, and Gurkha troops. His objective was to penetrate the Ngari region of western Tibet, a territory dominated by inhospitable landscapes and severe climatic conditions. Despite logistical challenges, Zorawar Singh displayed exceptional strategic foresight, leading his army across the arduous passes of the Himalayas.

The initial stages of the campaign witnessed remarkable victories, including the capture of Gartok and Taklakot, key Tibetan strongholds. However, the onset of winter brought unprecedented hardships. Freezing temperatures, dwindling supplies, and unfamiliar terrain began to erode the morale and physical endurance of the Dogra forces. Taking advantage of these vulnerabilities, Tibetan troops, reinforced by Qing forces, launched a counteroffensive.The decisive encounter occurred near Taklakot in December 1841. Zorawar Singh, displaying characteristic valor, led his troops into battle despite overwhelming odds. In a fierce engagement marked by close combat and strategic maneuvers, the Dogra forces were ultimately encircled and overwhelmed. Zorawar Singh fell in battle, and his death marked the end of the Dogra campaign in Tibet.

While the Tibetan forces emerged victorious, the campaign underscored Zorawar Singh’s indomitable spirit and strategic brilliance. His audacious attempt to extend the boundaries of the Dogra state into the Tibetan plateau remains unparalleled in the history of Himalayan warfare. His death symbolized not just the loss of a great general but also the limits of expansionist ambitions in the face of extreme environmental and logistical challenges.

Despite initial successes, Zorawar’s campaign faced setbacks due to strategic miscalculations, particularly underestimating Tibetan forces’ ability to exploit the Matsang Pass in winter. In December 1841, his army, unprepared for severe weather and relentless Tibetan resistance, suffered heavy losses. Zorawar himself was mortally wounded during the Battle of Taklakot. His severed head was later displayed in Lhasa as a symbol of Tibetan resistance, yet his valor was immortalized through the "Singh ba Chorten" or the Cenotaph of the "Singh Warrior". "Singh ba Chorten" as called by Tibetans, translated as "Cenotaph of the Singh Warrior", Taklakot, Tibet. About the soldiers who were taken into captivity, Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, who served as Tibet's Secretary of Finance from 1930-1950, writes in his book, TIBET - A Political History: "Over three thousand Sikhs were killed in the course of the foray. Seven hundred Sikhs and two Ladakhi ministers were taken prisoner. The remainder of the defeated army fled.... Those prisoners wishing to return to their country were allowed to do so..... One third of the Sikhs and Ladakhi prisoners elected to remain in Tibet. The Sikhs were resettled in warmer regions of Southern Tibet by the government and many married Tibetan girls. The Sikhs are known to have introduced the cultivation of apricots, apples, grapes and peaches into the country."

Posthumous Diplomacy and Geopolitical Settlements

The death of General Zorawar Singh in the Battle of Taklakot in December 1841 marked a turning point in the Dogra expansionist campaigns and significantly altered the political dynamics between the Dogra state, Tibet, and the Qing Empire. In the aftermath of his demise, a series of diplomatic negotiations and military recalibrations unfolded, ultimately culminating in a formal settlement that delineated territorial boundaries and defined the power dynamics in the Himalayan region.

The immediate aftermath of Zorawar Singh’s death saw the Tibetan and Qing forces pursuing Dogra remnants and reclaiming lost territories, including Taklakot and surrounding regions. However, the Dogra state, under Raja Gulab Singh, was determined to recover its position in Ladakh and maintain its territorial integrity. In 1842, a renewed Dogra campaign was launched under the command of Dewan Hari Chand and Wazir Lakhpat Rai, who succeeded in halting Tibetan advances and regaining key positions in Ladakh.

The protracted hostilities eventually led both sides to seek a diplomatic resolution. The Treaty of Chushul, signed in September 1842, marked the conclusion of the conflict. This treaty was brokered by representatives of the Dogra state, the Tibetan authorities, and the Qing Empire. It established a clear boundary between Ladakh and Tibet, affirming the status quo ante bellum and prohibiting future invasions by either party. The treaty further ensured the continuation of trade relations across the Himalayan passes, which were vital for the economies of both Ladakh and Tibet.

The settlement signified the Dogra state’s recognition of the limits of territorial expansion into the Qing-dominated Tibetan plateau. At the same time, it underscored the strategic resilience of the Dogra rulers, who retained control over Ladakh despite the temporary setbacks during the Tibetan campaign. The treaty also reflected the Qing Empire’s interest in stabilizing its frontier regions and preserving its suzerainty over Tibet.

The death of General Zorawar Singh thus became a catalyst for a broader geopolitical settlement that defined the contours of Himalayan politics in the mid-19th century. While his demise curtailed Dogra ambitions in Tibet, the Treaty of Chushul preserved Ladakh’s integration into the Dogra domain and ensured a fragile but enduring peace between the neighboring polities.

A Portrait of Leadership and Valor

General Zorawar Singh (1786–1841) stands as a towering figure in the annals of Indian military history, celebrated for his unparalleled strategic acumen, indomitable spirit, and remarkable contributions to the territorial expansion of the Dogra kingdom under Maharaja Gulab Singh. His campaigns, marked by audacity and meticulous planning, not only reshaped the political boundaries of the northern subcontinent but also demonstrated an extraordinary ability to adapt to the challenges posed by the harsh Himalayan terrain.

Born in a humble Rajput family in the village of Ansar of Haripur tehsil in Kangra, Zorawar Singh’s rise to prominence was marked by his unwavering commitment to duty and an exceptional talent for military strategy. Early in his career, his administrative efficiency in managing the territories of Kishtwar under Raja Gulab Singh brought him into the limelight, earning him command of Dogra forces. His rise exemplified the meritocratic ethos that prevailed in the Dogra military establishment, where talent and loyalty were rewarded with opportunities for leadership.

Zorawar Singh’s campaigns into Ladakh (1834), Baltistan (1840), and Tibet (1841) showcased his visionary leadership and ability to execute complex military operations under challenging circumstances. His conquest of Ladakh was particularly notable for its strategic brilliance and logistical ingenuity. Despite facing formidable natural obstacles such as high-altitude passes, freezing temperatures, and logistical shortages, Zorawar Singh led his troops to resounding victories, cementing his reputation as the “Napoleon of the East.”

What set Zorawar Singh apart was not merely his military accomplishments but also his statesmanship and humane approach to governance. His ability to integrate the newly conquered territories into the Dogra state through administrative reforms and respect for local customs won him the loyalty of the indigenous populations. He also ensured the protection of trade routes, fostering economic stability in the region.

Tragically, Zorawar Singh met his end in the Battle of Taklakot during his ambitious campaign into Tibet in 1841. Despite the loss, his legacy endured as a testament to the resilience and determination of the Dogra state. His exploits inspired future generations and left an indelible mark on the collective memory of the region.

General Zorawar Singh’s expeditions not only expanded the Sikh Empire but also established a legacy of military ingenuity in extreme conditions. His contributions hold enduring significance, particularly in the geopolitics of the Himalayas, as his annexations laid the groundwork for India’s modern territorial boundaries. Zorawar Singh’s life exemplifies the virtues of courage, strategic vision, and unwavering commitment to duty. His legacy remains a source of inspiration for leaders and soldiers alike, offering timeless lessons in leadership, perseverance, and the pursuit of excellence in the face of adversity.( Photos courtesy: Author)

REFERENCES

1. Bakshi, S. R. Zorawar Singh: The Conqueror of Ladakh. Delhi: Radha Publications, 1991.

2. Bose, Manmath Nath. The Indian Hero Zorawar Singh: A Great General. Calcutta: Chuckervertty, Chatterjee & Co., 1957.

3. Charak ,Sukhdev Singh. General Zorawar Singh,New Delhi:Director Publication Division. 1983

4. Hasrat, Bikrama Jit. Life and Times of Ranjit Singh. New Delhi: V. V. Research Institute, 1977.

5. Kaul, H. N. Rediscovery of Ladakh. New Delhi: Indus Publishing, 1998.

6. Lamb, Alastair. The Sino-Indian Border in Ladakh. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960.

7. Moorcroft, William, and George Trebeck. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab. London: J. Murray, 1841.

8. Petech, Luciano. The Kingdom of Ladakh (c. 950–1842 A.D.). Rome: IsMEO, 1977.

9. Rai, Mridu. Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

10. Rizvi, Janet. Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983.

11. Sufi, G. M. D. Kashmir: A History. New Delhi: Light & Life Publishers, 1974.

12.Tsepon W.D.Shakabpa: Tibet:A Political History:Potawatomi Corporation,New Delhi,1984

13. Zutshi, Chitralekha. Kashmir’s Contested Pasts: Narratives, Sacred Geographies, and the Historical Imagination. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014.