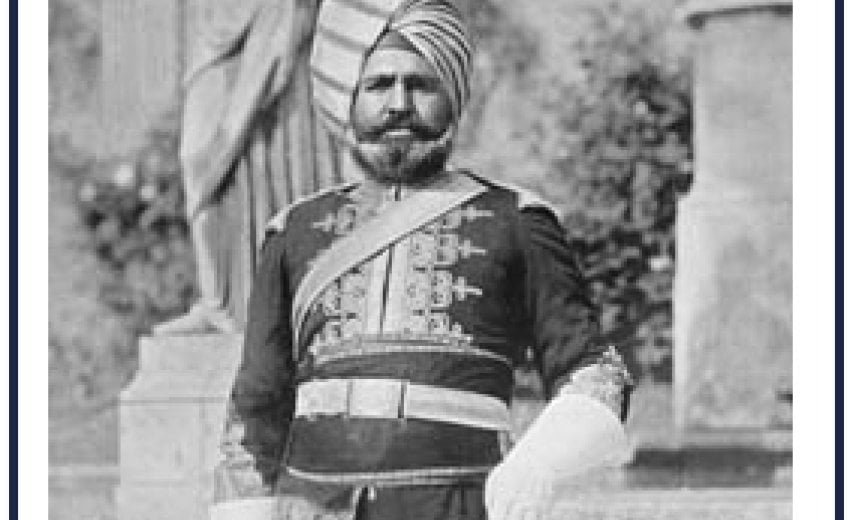

Sikhs have a strong history in the military, always stepping up to serve their country. During WWI, more than 65,000 Sikh soldiers and over 300,000 in WWII showcased their bravery. Today, we pay tribute to these heroes and highlight the unique story of Pvt. Buckam Singh.

Pvt. Buckam Singh's resting place at Kitchener Mount Hope Cemetery is the only military grave of a Sikh soldier in Canada from the World Wars. Wounded twice in the battlefields of France during WWI, Pvt. Buckam Singh was one of the 9 Sikh soldiers allowed to serve with the Canadian Forces in that war. His war medal and military grave, once forgotten, have become a proud part of the Sikh community's heritage and a heroic tale reclaimed by Canada.

Buckam Singh's Early Years

Buckam Singh was born on December 5, 1893, in Mahilpur, Punjab. His parents were Badan Singh Bains and Candi Kaur. At the tender age of 10, in March 1903, Buckam got married to Pritam Kaur from Jamsher in the Jalandhar District of Punjab. Back then, it was common in Sikh families to arrange marriages for their kids early.

Even though Buckam and Pritam were married young, they couldn't live together or even see each other until they became adults. There was a special ceremony called Muklawa, usually held when they reached adulthood, to make their marriage official. This was the tradition at the time.

Sikhs in Canada: Struggles and Opportunities

In 1887, the first Sikhs came to Canada. They were soldiers invited for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee celebrations in London. While traveling across Canada by train, they were captivated by its stunning landscapes and fertile farmland, reminiscent of their Punjab homeland. The news spread, and soon more Sikhs embarked on a journey to start a new life in Canada. One such pioneer was Buckam Singh, who, at the age of 14, left for Canada in 1907.

During that time, Sikhs already in Canada faced a challenge—they couldn't bring their families. Authorities hoped that by separating them from their wives and children, most Sikhs would eventually return to Punjab. Only nine women were allowed to immigrate to Canada between 1904 and 1920. Buckam Singh dreamt of reuniting with his wife, Pritam Kaur, in Canada, but those hopes were shattered.

In the early 1900s, immigration laws and union policies in Canada limited the job options for Sikh immigrants. Even if they were educated professionals like machinists, doctors, or engineers, they could only find low-skilled manual labor on farms, railways, sawmills, or mines. This was a tough situation for people like Buckam Singh, who, despite his skills and background, found himself working in B.C.'s mining industry.

Sikhs faced barriers beyond employment – they were not allowed to vote, hold public office, work in civil service jobs, bid for public works contracts, practice law or pharmacy, or buy Crown timber. Despite succeeding in a few professions, Sikhs were still excluded from many opportunities. Feeling limited by these conditions, 20-year-old Buckam Singh made a decision in 1912/1913 to leave British Columbia and explore new opportunities and adventures in Ontario.

From Farming to Frontlines: Buckam Singh's Decision to Join the Military

Buckam Singh was one of the early Sikhs living in Ontario. Before him, Dr. Sundar Singh was the first documented Sikh in Ontario. He was sent by the British Columbia Sikh community to speak up for their rights. Dr. Sundar Singh gave public talks in Toronto from 1911 to 1917. Later, Buckam Singh worked on W.H. Moore's farm in Rosebank, Ontario, for about six months. Eventually, inspired by the events of World War I, he decided to join the military.

In 1914, when Great Britain declared war on Germany, Canada, as part of the Empire, joined the war the next day. This marked the first instance in Canadian history where its forces fought as a distinct unit under a Canadian commander born in Canada.

At first, people from different backgrounds weren't really accepted. When 50 black individuals from Sydney, Nova Scotia wanted to help, they were told, “This is not for you fellows, this is a white man’s war.” By 1915, things got a bit better, and minorities like blacks, indigenous people, and Japanese Canadians were allowed to join the military. But, they often had to be in separate groups, doing things like traveling and camping on their own.

What's interesting is that Buckam Singh and eight other Sikh Canadian soldiers, who bravely served in The Great War, were not kept apart in special units. Instead, they were part of the regular Canadian battalions, which was different from how others were treated in segregated units.

Patriotism and Duty

In April 1915, at the age of 22, Buckam Singh left W. H. Moore's farm in Rosebank, Ontario, and headed to Smith Falls, Ontario. There, he joined the 59th Infantry Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. On April 23, 1915, Buckam Singh officially pledged his loyalty to King George the Fifth by signing his Attestation Papers and was given the regimental number 454819.

Following this, Buckam Singh underwent a medical examination and training at Barriefield Camp near Kingston. Lt.-Col. H.J. Dawson led the 59th Battalion during this time. Interestingly, on the Attestation Paper, Buckam Singh's name is recorded as 'Buk Am Singh,' while he signed it as 'Bukam Singh.' The document listed his height as 5 feet 7 inches with a swarthy complexion.

It's worth noting that the religious denomination section in the form had limited options like Church of England, Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, Other Protestants, Roman Catholic, or Jewish. This posed a challenge for Sikhs and those of other religions who were often assigned the default option of 'Church of England' by administrative clerks. This lack of accommodation highlights the need for more inclusive choices on such forms.

During World War I, as Canadian soldiers faced increasing losses in battles like Neuve Chapelle and the Second Battle of Ypres, where poison gas was used by the Germans, troops in Canada needed to be quickly sent to Europe. The urgency meant that soldiers couldn't have lengthy basic training. In a 48-hour period at Ypres starting on April 24, 1915, Canadians suffered over 6,000 casualties, with one in every three men being affected. The situation called for immediate action.

The 59th Battalion, like many others formed in early 1915, sent two groups of about 250 men in the summer and fall of that year. However, the main group didn't set sail until the spring of 1916. Buckam Singh was part of the initial contingent that left from Montreal on August 27, 1915, aboard the troop ship S.S. Scandinavian 2. Traveling at a top speed of 15 knots, Buckam Singh and his fellow Canadians reached England one week later on September 5, 1915. The journey marked the beginning of their significant contribution to the war effort.

When Buckam Singh arrived in England, his battalion joined reserve units. From there, soldiers were sent to support different divisions of the army. Some went to back up the 1st and 2nd Divisions, while others joined the 3rd and 4th Divisions, which were still being formed in England. Buckam Singh, too, was moved to the 39th Reserve Battalion, waiting for his assignment to a combat unit that required reinforcements.

In the Fields of Flanders

Flanders is a region in Belgium, named after an old area that covered parts of modern Belgium and Northern France. During World War I, soldiers often called their duty on the Western Front "France," whether it was in France or Belgium. The main town in Flanders where a lot of the fighting happened was Ypres, and the surrounding area was called the Salient. This region saw battles from October 1914 almost until the war ended in November 1918.

In January 1916, when Buckam Singh reached France, he joined the 20th Battalion after being moved from the 39th Reserve Battalion. Throughout the war, he stuck with the 20th Battalion. They were part of the 4th Brigade, 2nd Division, Canadian Corps, and stationed in the Ypres Salient near Messines. Their duties included nightly patrols in no man's land, fixing wire and trenches, and facing constant enemy shelling.

During the winter of 1915-16, the routine involved spending 18 days on the front and 6 days in the rear, dealing with challenges like lice, trench foot, and disease. In March 1916, everyone received steel helmets for protection. In the spring of 1916, the Commander of the British Second Army decided it was crucial to eliminate an enemy stronghold near St. Eloi.

Following numerous attacks and counter-attacks, the 4th Brigade aimed to reclaim craters that the 6th Brigade had to retreat from. The 20th Battalion successfully recaptured one crater, enduring a month of intense shelling. In this period, the 4th Brigade suffered a total of 1373 casualties.

During World War I, Sikhs from Canada weren't the only ones who fought. Sikhs were part of the action in Europe, including battles in places like Flanders (Ypres, La Bassee, St. Julien, Festubert), Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, and Africa. At the war's start, 124,000 men from the Punjab region were in the British Indian Army. Three years later, that number had grown to a quarter of a million.

Among them, Sikhs made up about 65,000 soldiers, which was 26% of the Punjabi total. Surprisingly, Sikhs represented only 14% of Punjab's male population of fighting age. Despite these odds, almost 1,500 gallantry awards were given to Punjabis, with Sikhs receiving 700 of them. Their bravery and contribution during the Great War were significant and deserve recognition.

Casualty of War

The Battle of Mont Sorrel happened near Sanctuary Wood during World War I. It was fought between Canadian and German forces from June 2 to June 14, 1916. The Canadians, along with the UK's 20th Light Division, faced Germany's XIII (Royal Württemberg) Corps. Initially, the Germans took control of most of Mont Sorrel, also called Hill 62. However, the Canadians managed to reclaim the hill, but the victory came at a high cost, with nearly 8,000 Canadian casualties.

During the battle, soldiers like Buckam Singh faced danger. On June 2, 1916, he got injured in the head by a shrapnel, noted as a gunshot wound in his medical report. He was quickly taken to the No. 8 Stationary Hospital at Wimereux. The next day, he was sent to the No. 5 Convalescent Depot at Boulogne to recover. By the end of the month, Buckam Singh had sufficiently healed, and on June 29th, 1916, he rejoined the 20th Battalion in the field.

Less than three weeks after rejoining the 20th Battalion, Buckam Singh got injured again during a battle. It happened on July 20, 1916, at St. Eloi, where he was seriously hurt by a bullet in his left knee, breaking his leg below the joint. He quickly went to No. 3 Canadian General Hospital in Boulogne for treatment. This hospital wasn't just any hospital – it was led by the famous Canadian soldier, poet, and doctor, Lt. Colonel John McCrae, best known for writing the well-known war memorial poem ‘In Flanders Fields’.

After being treated by Lt. Colonel John McCrae, Buckam Singh was sent to England on July 23, 1916, to recover from his injuries. He sailed across the English Channel on the Belgian Hospital Ship Jan Breydel.

Recovery and Challenges in England

Buckam Singh sailed across the English Channel on the Belgian Hospital Ship Jan Breydel. After that journey, he stayed in various hospitals to heal from his injury. The British government set up hospitals specifically for Canadian troops, and Buckam Singh, being Canadian, received care in these facilities. Other nations' troops had their own separate hospitals.

Sikhs in the British Indian Army, like Buckam Singh, were treated at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. This place had been transformed into a hospital for Indian patients because its exterior resembled an oriental palace, offering a familiar touch of home to the troops. On July 24, 1916, Buckam Singh entered the 2nd Western General Hospital in Manchester, where he spent two months recovering from his leg wound. During this time, a reporter from The Toronto Daily Star interviewed him. The newspaper reported his serious illness back home on August 9, 1916.

In September 1916, Buckam Singh entered the King’s Canadian Red Cross Convalescent Hospital at Bushy Park, Hampton Hills. He needed care, and after four weeks of massage therapy, doctors decided he was recovering well. On November 4th, 1916, he moved to the Canadian Military Convalescent Hospital, Woodcote Park, Epsom.

By December 22nd, Buckam was declared fit for discharge. On March 11, 1917, he found himself at West Sandling Camp, north of Maidstone, Kent, waiting at the Central Ontario Regimental Depot. He anticipated his return to the front lines in France.

The Last Battle

As Buckam Singh prepared to go back to the war in France and join the 20th Battalion, he faced an unexpected and tough battle. After Christmas in 1916, he developed a bad cough that kept getting worse. His overall health deteriorated, and by March 19th, 1917, he had to go to the Canadian Military Hospital at Hastings because doctors suspected he had tuberculosis.

Two weeks later, on March 28th, things got so serious that Buckam Singh underwent surgery to remove fluid from his right lung. The news got even worse the following week when he learned that the tests for tuberculosis came back positive. This was a huge blow to him, and his fight against this unexpected enemy had just begun.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, tuberculosis, also known as "consumption," was a major health concern. In 1918, one out of every six deaths in France was due to TB, and around 100 million people worldwide lost their lives to the disease in the 20th century.

Buckam Singh, who spent time in crowded army barracks, faced a high risk of contracting TB. Unfortunately, he fell ill before the first general vaccine was created in 1921. It wasn't until 1946, with the development of the antibiotic streptomycin, that effective treatment became possible. During Buckam Singh's time, the only option for infected individuals was quarantine.

With his combat days behind him, Buckam Singh now had to battle tuberculosis from a hospital bed and in isolation. On May 5th, he was discharged from the Hastings hospital, and plans were made to take him home along with other TB patients in quarantine. Buckam Singh made the journey across the Atlantic on May 11, 1917, aboard the hospital ship HMHS Letitia, which docked at Halifax, Nova Scotia.

After reaching Halifax, Buckam Singh, who was very sick, took a long train ride to Ontario. He was released from duty in Guelph, Ontario, on August 1, 1918, because he was not fit for more war service. He had served for 3 years and 100 days in total. A medical report showed that he weighed only 127 lbs, had a bulge over his right lung, and had a weak voice with faint breath sounds and fluid present. The report also mentioned a shrapnel scar on the right side of his head and a bullet scar through the top of his left leg bone. A medical board suggested at least another year of treatment at the Freeport Sanatorium Hospital in Kitchener, Ontario.

The Battle Ends

After struggling with tuberculosis for about two and a half years, Buckam Singh, the brave Sikh Canadian hero, fought his best battle at Freeport hospital for over a year. Sadly, at the age of 25, he lost the fight and passed away on August 27, 1919. Despite being alone in Ontario with no family or Sikh community around, the Canadian military honored him with a respectful burial at Mount Hope Cemetery in Kitchener, Ontario. To this day, Private Buckam Singh's grave remains the only known Sikh Canadian World War I soldier's grave in the country.

Legacy and Honoring Pvt. Buckam Singh

Recently, the discovery of Private Buckam Singh's Victory Medal has unveiled a remarkable tale of courage and adventure. Although he died without his family by his side, he has now been reunited with his fellow Sikh Canadians, bridging a gap of almost a century. Buckam Singh's story of bravery, valor, and sacrifice for his country will be shared and celebrated by generations of Sikh Canadians. His memory, once nearly forgotten, is now alive and thriving in the hearts of those who honor his legacy.

Letter from Pvt. Waryam Singh, 38th Battalion (Eastern Ontario Regiment) Canadian Expeditionary Force, Nov 1916, France, later wounded Apr 1917.

“Shells and bullets were falling like rain and one’s body trembled to see what was going on. But when the order came to advance and take the enemy’s trench, it was wonderful how we all forgot the danger and were filled with extraordinary resolution. We went over like men walking in a procession at a fair, and shouting, we seized the trench and took the enemy prisoner."

*Based on an article by The Sikh Foundation Int'l, published on 9th December 2011