Like most Sikhs, we too have attended oodles of discussions on and about Sikhi over the years. The attendance is often heavy with both young and old Sikhs, and we parse issues that confront us, our colorful history, and our direction forward.

The primary purpose: to engage both young and old in an inter-generational conversation. Quite expectedly, the the narrative often highlights the nobility of Sikh teachings and ideals, and our slipshod practices. Some speakers aim at our silly ways and rue the inevitability of the times. We often condemn others: often Hindus or the British for the debasement of Sikh practices. And that’s where the story usually ends until we meet, to revisit similar themes again.

And we wonder: Surely, as adults, we Sikhs have some meaningful role in this inevitable decline of Sikhs and Sikhi, or don’t we?

Hence this diatribe. The past often appears rosier in retrospect. We won’t overlook the times of Sikh glory – the worldly triumphs we had while remaining reasonably connected to our religious roots and practices.

True that in the period of the Gurus and immediately afterwards, there were hair-raising battles with both Mughal rulers (Muslims) as well as the Hindu majority. The third way (Sikhi) was not acceptable to either of the two larger religions in India. There was often a hefty price on a Sikh’s head if he openly lived with the markers of his faith. Sikhs and Sikhi were then perceived as threats to the philosophy and power of the establishment — Muslims and Hindus.

But within decades after Guru Gobind Singh, Sikhs had fought their way to triumph. They established Sikh governance in the greater Punjab, even extending into Tibet and Afghanistan. The outstanding Sikh General, Hari Singh Nalwa, was able to command and control Afghanistan. Much of India, too, tasted a degree of independence as Muslim dominance collapsed. The larger India returned to several quasi-independent nation-states. For much of this we credit the over two-centuries of Sikh struggle, largely in Punjab and other pockets.

These historical realities along with the struggle for independence shaped north-western India – largely Punjab and Punjabis. Until the British and French came by sea, all traders, invaders, conquerors, Greek hordes and early Aryan settlers entered India via the Khyber Pass through the northwest corner that connects Afghanistan to Punjab. (Now half of Punjab constitutes Pakistan, the other half is part of India.) This prolonged hybridization of Punjab enriched its genetic pool, resulting in greater vigor. We find similar enrichment in the Balkans and the United States as well.

It is not surprising then that Punjabis (primarily Sikhs) led the fight to seal the Khyber Pass to every wannabe conquistador. Such a transformational shift is not attained in a day or even a year. Early results, however, were evident within decades of the post-Guru period (the times of Banda Bahadur.) It took the Sikh message about 240 years and 10 generations of Gurus to become realized.

The next 50 years were the Golden Age for Punjab; Sikhs ruled the greater Punjab, justly and sagaciously; land reforms were established. All three religions – Hindus, Muslim and Sikhs – were treated justly and equally, and lived in peace. The ruler then was a Sikh, Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

In the meantime, the British had entered India by sea and conquered almost all of India. A hundred years later the British annexed Punjab in battles where non-Punjabi Indians sided with them against the Sikhs. It is true that the British won by perfidy and betrayal by some of the non-Sikh commanders in the Sikh army.

We usually mark this as the time when Sikh values, teachings and practices began their downward slide; today the rot continues.

Why and how?

Centuries of immigration and hybridization shaped the Punjabi mindset. They are a pragmatic people. In the British-Sikh wars Hindus and Muslims aided the British. The British won the battles but learned to value and respect Sikh skill, will, strength, dedication and determination in war. So, they preferentially recruited Sikhs into the army, and opened many English-speaking schools – in fact, they made allies of Sikhs and encouraged them as faithful friends. At one time 40% of the British-Indian army officers were Sikh. More significantly, the British encouraged, nay required, that Sikhs maintain their articles of faith while serving in the army. The Sikhs saluted the Guru Granth at their recruitment. Thus, the British ensured Sikh loyalty.

This was very shrewd of the British, we would say. It is equally obvious that Sikhs (the ruler Ranjit Singh, his statesmen and generals of the time) lacked the foresight to look beyond their own lifespans. Coming to terms with our own shortcomings is never easy but such are the necessary lessons here. Perhaps Sikhs put aside their times of struggle too readily and forgot to remain vigilant! Did they forget that those who do not remember their history live to repeat it?

How did the pragmatic Sikhs see the new reality emerging in front of their eyes? Clearly, their new world would be ruled by the British. The British led Indian army provided them a semblance of Westernization and dignity. This shaped their reality and the nature of their future. The Sikh connection to, and reliance on, their primary traditional institutions, particularly the gurduara, lessened. The gurduara and its granthi were transformed and, in fact, dramatically down-graded, largely by these changed ground realities.

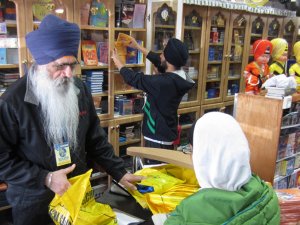

Engrossed in their new realities, expectations, standards of living and behavior, Sikhs increasingly delegated the responsibilities of their religious institutions and education to granthis, who effectively became caretakers of gurduaras rather than specialists in education on Sikhi.

Look around: The granthi, often the most educated person in the community, whether in the village or even in the best Indian urban setting has now become somewhat of a “gofer.” (Before you take umbrage at our blunt assessment, we ask you instead to look at the reality.) At the gurduaras around you, how often do you see scholarly exchange or extended vichaar to improve your connection to Sikhi? Our officer-corps, whether civilians or from the armed services — largely Sikhs in the latter — are some of the most westernized Indians. But the British insisted that the turban and long unshorn hair of the Sikh soldier be maintained. They strongly enforced it.

This is how the British won the loyalty of the Sikh servicemen and the Sikh community. The British-led Indian army necessarily created a hybrid Sikh culture. The Sikhs responded positively to the respect and consideration they sought. Even the rural Sikhs saw that token westernization would be a powerful path to material and worldly success. No surprise then that the gurduara inevitably became more symbolic than meaningful to the Sikhs. As we said, life had made Punjabis and Sikhs into a superbly pragmatic people.

How well had Punjab evolved in only 240 years or so, with 10 Gurus? Sikh ascendancy and rule had been quick, efficient and effective. But it disappeared even faster. Why? Genetic hybridization had created a very pragmatic people. How they saw the future? How the British saw the Sikh talent pool? How they came together in mutual respect!

The British played a shrewd, measured and winning hand. They courted and won Sikh friendship, even though in India’s’ struggle for independence fully 65 to 68 percent of all freedom fighters who were hanged by the British or sentenced to life imprisonment were Sikhs. The Sikhs were a minority as they still are — barely two percent of India’s burgeoning billion. The larger Indian society gave them little support then, and offers even less today.

Under the British, 40% of the officers in the Indian armed services were Sikh, but this is not true anymore in free India. Sikhs remain a minority but they did not get swallowed up by Hinduism, as Buddhism and Jainism did. We think the independent Sikh identity saved them from Indian mythology’s Boa Constrictor embrace. Hinduization still impacts us, often passively, because of large Hindu numbers, cultural misinterpretation and miscegenation.

Our cultural habits have become largely secular in an attempt for the minority to merge with the mainstream. Think back: What are the early lessons — essential advice — drummed into the head of Indian children and adolescents irrespective of their religious identity? They begin and end with: study hard, get good grades, get a good stable job and marry well. Isn’t that a fair summary of what was drummed into our heads? Where is Sikhi in this truly secular message? Sikhs essentially did what a pragmatic people would do.

In fact, our relationship to the two languages critical to us changed dramatically. Competence in English defined our proficiency at work in the new world. Skill in Punjabi defined us within our community. We never saw the need to pick up a book on poetry, history or philosophy in English because it would likely not be work-related, and we didn’t pick up a book on philosophy, history or poetry in Punjabi because Punjabi had become increasingly limited to social banter and easy, crass humor.

Ergo, the life of the mind became increasingly unexplored in English or Punjabi.

In this mixed and sometimes sorry tale, Sikhs too have a responsibility for their place in contemporary Indian society. Let’s sketch it briefly.

Free India’s policies today disrespect the Sikhs in history, in religion or in their place in society, in fact India seems to be on a path that ignores Sikhs entirely while Sikhs are too busy to even notice. For a minority, as Sikhs are, the drive for material success outweighs Sikh teachings and values. But where is accountability?

Just look at Bollywood, often seen as the culture of modern India! Sikhs are a presence there, but as buffoons, for the cheap joke and easy laugh, without a thought about the damage to our image in the larger society. Punjabi music, catchy as it is, promotes liquor and drug culture and we don’t notice. Why don’t we produce good literature, wholesome entertainment, great music (remember music is in our blood) and movies for the mainstream population for meaningful impact on society rather than following the rotten Bollywood path? Do we have shortage of talent or skills, or is it common sense that is missing?

We need some introspection and we need to own our responsibility rather than shifting the blame to the British or Muslims or Hindus or the Indian government, gurduaras, granthis and management.

We need to be proactive rather than being retroactive in damage control. We need to rediscover what Gurbani means to us, and what we want for and from Sikhs and Sikhi. Just repeating lines of Gurbani – parrot like – won’t work (Dithae mukt na hovaee jitcher sabd na karay vitchar, Guru Granth p. 594.)

Our focus needs to shift from more and expensive vestments (rumalas) for the Guru Granth, or gold and marble in gurduaras to our own community and its education and understanding, so that we become a more progressive people. We need to learn lessons from Jews!

Our downhill slope is not the invention of the British, Muslims and Hindus alone; we, too, have collaborated mightily along the way. An equal place at the table of this or any society should define our goal.

T.S. Eliot reminds us of “the cunning passages and contrived corridors of history that deceive us by vanities.” Stay in touch with Sikh history and you will become an optimist – multi-layered and incredibly complex.

The rot set in more than 150 years ago; it continues today. Isn’t it time to say ENOUGH? It’s for us to define and construct the cure. The buck stops with us.