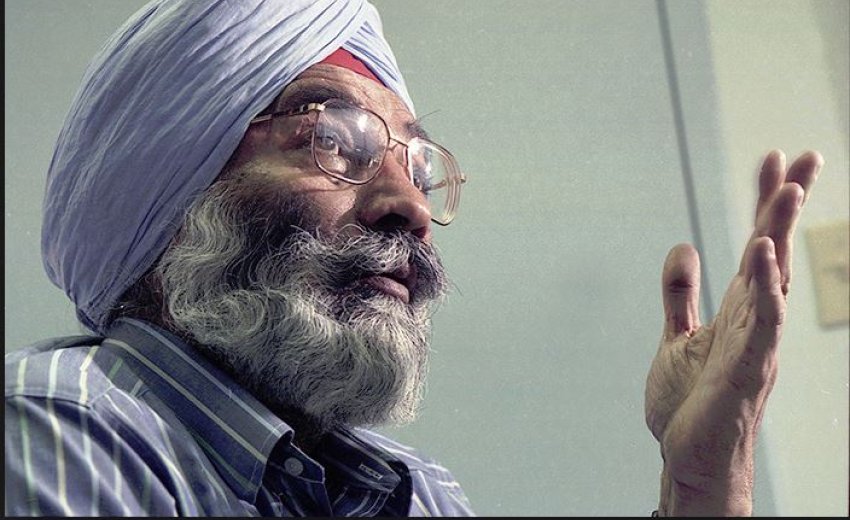

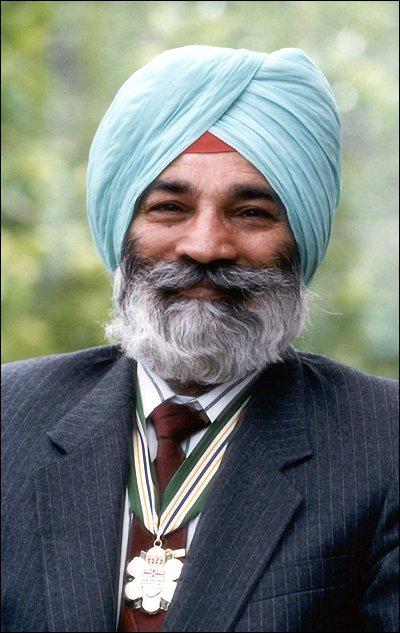

18  November marks the 10th anniversary of the first assassination of a journalist in Canadian history. I hope my colleagues remember the victim's name. Tara Singh Hayer deserves to be remembered alongside such famous martyrs to their craft as Daniel Pearl and Anna Politkovskaya.

November marks the 10th anniversary of the first assassination of a journalist in Canadian history. I hope my colleagues remember the victim's name. Tara Singh Hayer deserves to be remembered alongside such famous martyrs to their craft as Daniel Pearl and Anna Politkovskaya.

Hayer was the publisher of the Indo-Canadian Times, a Punjabi weekly printed in Surrey, B.C. An Indian-born Sikh, Hayer once embraced the cause of Sikh separatism - and even the military struggle to liberate "Khalistan" from India. But he changed his mind in the 1980s, as he saw corruption and terrorism infect the movement. When Sikh separatists bombed Air India Flight 182 in 1985, Hayer's newspaper took sides against the militants.

Three years later, a man walked into his office and shot him twice at point-blank range. Hayer survived. He would spend the next decade, crippled but unbowed, in a wheelchair.

In 1995, Hayer revealed to the RCMP why he'd been targeted. In the Fall of 1985, several months after Flight 182 exploded, Hayer visited his friend Tarsem Singh Purewall at the offices of the newspaper he owned, Des Pardes, in the suburbs of London, England. During the meeting, Purewall received another Canadian visitor: Ajaib Singh Bagri, who would subsequently be tried (and acquitted) for the Flight 182 bombing. According to Hayer's October 15, 1998 statement to the RCMP, Bagri and Purewall recused themselves to a nearby cubicle for a private discussion - but spoke loud enough for others to hear:

"Bagri stayed talking to Purewal for about one hour during which time the subject of the Air India Flight 182 bombing came up. Purewal asked Bagri how he managed to do that. Bagri replied that they (the Babbar Khalsa [separatist group]) wanted the government of India to come on their knees and give them Khalistan." Had Hayer been able to testify at the Air India criminal trial, the infamous 2005 result might have been different. But on November 18, 1998, he was gunned down in his garage - this time fatally - thereby rendering his statement inadmissible.

Purewall, another one-time militant separatist who'd changed his tune after becoming disgusted with the Khalistani movement, was gunned down in 1995 under similar circumstances. The death toll in Air-India Flight 182 is listed as 329. I'd say the real number is at least 331.

Tara Singh Hayer was no saint. Like many publishers in the spectacularly fragmented and gossip-mongering Punjabi-Canadian media, he often went in for petty feuds and personal vendettas. But on the most important issue facing his community, he was utterly fearless. Despite numerous death threats, including open calls for his murder on Punjabi radio, Hayer kept pumping out articles attacking Khalistani Sikhs. How many journalists in this country, or any country, would have the guts to do this - even before they'd been rendered paraplegic by two rounds from a .357?

Ten years later, Hayer's memory has been preserved - at least among journalists and his fellow Sikh Canadians. Vancouver Sun reporter Kim Bolan (who herself has received numerous death threats for her outstanding coverage of Flight 182 and its aftermath) laid the facts out about Hayer in chapters 6 and 7 of her definitive 2005 book Loss of Faith. And in 1999, Canadian Journalists for Free Expression named their Press Freedom Award after the man.

At Sikh temples, where moderates and fundamentalists had for years been engaged in political battles, and even fistfights, Hayer's death galvanized the moderates. More than 2,500 people came to his funeral - including B.C.'s then-Premier. Even overseas, his death made news. Alongside all the other outrages committed in the name of Sikh separatism, Hayer's death helped sink the separatist cause to the point that, in 2008, the Khalistan movement is essentially moribund in the Punjab itself, even if diaspora firebrands continue to bang on about it.

Could Hayer's assassination have been prevented? In Loss of Faith, Bolan suggests the answer may be yes. Following the first attempt on his life, the RCMP ignored or bungled the numerous clues suggesting the hit was part of a larger conspiracy. Moreover, Bolan notes darkly, penetrating radical Sikh organizations brought the police up "against powerful people with connections to the highest political levels in Canada." What Bolan means is that Hayer wasn't just a stick in the craw of Canada's radical Sikhs, but also the slew of cynical politicians who rubbed elbows with all factions of the Sikh community in the sleazy game of ethnopolitics. In December, 1998, just a month after Hayer's funeral, none other than Prime Minister Jean Chrétien appeared at a fundraising dinner attended by Ripudaman Singh Malik and various other Flight 182 suspects. In recent years, Liberal leadership contenders have been encouraged to make the rounds of the country's less reputable Gurdwaras in search of warm bodies to bring to conventions. Even as recently as 2007, B.C. Premier Gordon Campbell, Surrey Mayor Dianne Watts and assorted other politicians attended an openly Khalistani Sikh parade whose participants included well-known alumni of notorious Air-India-era radical groups.

This sort of event is not only a disgrace to Canadian values, but also to the memory of Tara Singh Hayer. A Canadian patriot, he died in the fight against terror and radicalism. Not many of us would be prepared to make that kind of sacrifice. But surely we can at least avoid shaking hands with his enemies.