I admit that teaching and learning are very close to my heart. Why? Because that's all I have really done pretty much all my life. But it wasn't poetry, history or philosophy that I played with, not even rocket science, but human anatomy and related disciplines.

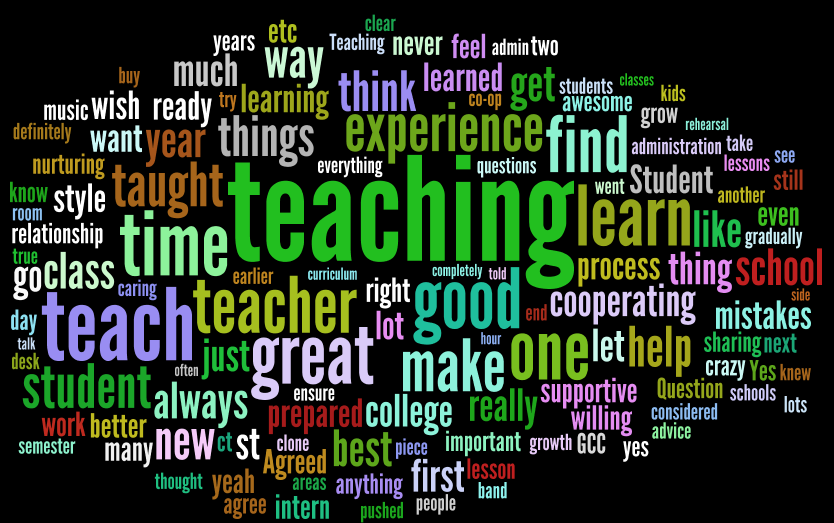

No matter the discipline teaching and learning are transactions. The question always is how best to teach so as to maximize the learning. Also keep in mind outcome assessment. The million dollar question is: what happens when the systematic teaching ends? Will further learning cease or will the student continue to accumulate layers of learning over a lifetime beyond the formal schooling?

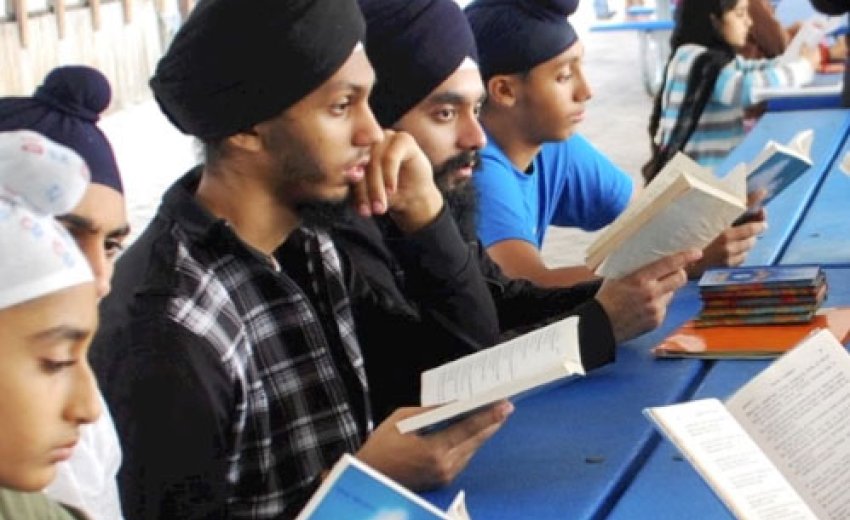

I have published several disparate essays on many aspects of learning and teaching in Sikhi; today I aim to pull some ideas together to foster a conversation. This never-ending issue was brought home recently by Dya Singh who drew a bead on how Sikhi is taught and learned in our gurduaras.

The justly celebrated Dya Singh is a musician par excellence and an exponent of both the traditional as well as experimental and imaginative waves in Sikh keertan tradition. His thoughts seemingly crystallized after a recently held week-long family camp on Sikhi in Australia for over 350 young and not so young Sikhs.

He opened the issue thus: "Is it time to switch our age-old learning and teaching of Sikhi from the 'Guru-Shishya' (teacher-pupil) method to that of the 'facilitator' method? The question arose at our latest 'camp' especially when some older folks had their entrenched views challenged. There is an age-old tendency of treating the sermons and views of brahmgianis, sants, raagis and percharaks as gospel. Can they be questioned? The younger generations are asking questions!"

Sure he celebrated the many inspiring preachers, teachers and keertanyas who stimulated student-teacher interaction and welcomed student participation, but even more he rued the many who hew to the tradition of overloading the listener with tons of information with nary an exchange - a one-way street indeed.

Now what does Dya Singh mean when he talks of a teacher-facilitator instead of a traditional granthi, kathakaar or raagi? And why should we embrace this model.

I suggest that the idea should not seem so alien to us. Let's come to it in a slightly round about fashion. Today, let's transfer some of the lessons of a lifetime to our pursuit of Sikhi.

How best to deliver the content of education in a student-teacher interaction? That is the question.

In a broad meaning of the term all communication is a form of dialogue, even if not all interaction is of the spoken variety. Human interface, even the most contradictory communication including war, is a form of dialogue. It is silence that isolates.

In the inevitable student-teacher interchange educationists talk about two kinds of dialogue - vertical and horizontal.

Feudal societies and hierarchal enterprises whether businesses or governments operate by a largely vertical model. All armies and most religions are prime examples of such vertical stratification of power. They show a pyramidal authoritarian structure with power concentrated at the top. It's a trickle down model of responsibility and authority somewhat like trickle-down economics that is most passionately promoted primarily by those who have made it.

Such a model is necessary to an army but to religions and civic societies it is poison. Yet those that acquire it, be they religious or civic systems, will die or kill for it rather than walk away from it.

Ergo the crusades, jihads and armed campaigns to convert or wipe out the "others" who are viewed as heathens, infidels or pagans.

From my limited vantage point, India remains the epitome of a superbly organized vertically stratified, pyramidal structure in every aspect of its existence - its caste system, family structure, schools, even its government and global businesses.

The Roman Catholic Pope, when he speaks ex cathedra from the Chair of Saint Peter on matters of faith and morals, remains the prime example of such unquestioned vertical authority.

I realize that even in democratic societies power is exercised from the top down but the source of all power is at the bottom in "We the People" and ceded to the leaders as needed.

In a vertical dialogue the message seeps downwards and in the process gets progressively degraded and distorted. And that is the fate of all religions as I see them. To me that's the best argument against gianis, granthis, mullahs, pundits, priests, ministers, shamans all -- middlemen between the people and the Creator.

In contrast the horizontal model of dialogue requires group participation. There is a moderator-facilitator as the mentor. Fresh ideas, from the most elementary to the supremely complex come in. Participation by all is encouraged or required. This is how good programs on graduate education function. And thus wisdom is created.

Now look at how the Gurus taught their message when they formulated the new society of Sikhi over 500 years ago? Not at all by fear or diktat, but by reason and example -- a horizontal dialogue -- often leavened by a dollop of humor. Let me illustrate my point by two well known parables from the life of Guru Nanak.

To drive home the futility of illogical rites and rituals we know that Guru Nanak appeared at a crowded Hindu sacred site at sunrise. The worshippers were splashing water to the rising sun. The Guru stood in the water and started splashing water to the west. He was scolded for not following the correct tradition - the water needed to be splashed to the rising sun because it was destined for the long dead ancestors of the people. The Guru patiently explained that he understood but at that time his crops, about 150 miles west, were parched for water. The people derisively told him that the splashed water could not reach that far. How then, he asked with simple humor could water reach somewhere in eternity to sate the dead ancestors. He taught like a man of the people that he was, not as one anointed to lead them and they understood.

He did something equally simple when on his way to Mecca he slept with his feet towards the holy place of Muslims. Once again he was severely reprimanded and brusquely asked to move his feet away. His answer disarmed the critics when he requested them to move his feet in the direction where God is not.

To me these are classic examples of a horizontal dialogue. Readers can easily find many such examples of teaching from the lives of Guru Nanak and the Gurus that followed him.

A dialogue among many guarantees just as many opinions, some even half-baked, and consequently many disagreements. The learning lies in working out through the many views and patiently allowing for clarity to emerge - and that may not always be quick or easy.

Guru Nanak founded the town of Kartarpur and nurtured its growth for more than a decade before handing the mantle of leadership to Guru Angad. Subsequent Gurus founded other towns across Punjab over the next two centuries. These towns attracted all kinds of people - the butchers, the bakers, the candle stick makers. Neighbors must have had doubts, questions and issues with their neighbors and friends. How did they resolve matters? Where did they appeal? They likely consulted the Guru. Again, examples of horizontal dialogue! Thus was the infrastructure of Punjab built.

In all of my years of teaching at a university for over half a century often I have told students (these are medical and dental students; bright and mature, not kids) that I am not here to teach anything to you, not even anatomy. And then I add, "In the ordinary sense of the word to teach would mean pouring information into you as if you are empty buckets. And if you are that then you are also bottomless buckets and whatever I pour in is going to fall out in time. My aim is to make it possible for you to learn what your talents and inclinations allow."

How to evaluate the outcome? I like to tell students that much as every new edition of a book must be better than the old or else it is only a reprint at best, similarly in time every child must excel the parent and every student must excel the teacher or else there is no progress.

I suppose this is what a facilitator does or should do. I agree entirely with Dya Singh that we need a cultural paradigm shift in the way our gurduara services run and that's never an easy trek - but it is oh so necessary.

Keep in mind the paradigm shift in India from Guru Nanak to Guru Gobind Singh took a good 240 years.

[email protected]

February 17, 2015