|

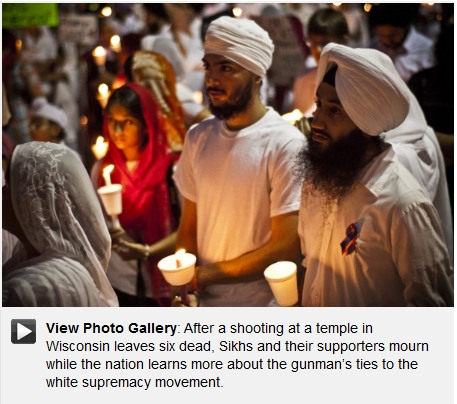

| Photo: AP |

In the aftermath of the mass shooting in a Sikh gurdwara in Oak Creek, Wis., a sea of reporters have asked many Sikh leaders and activists to quantify how many Sikhs had been targeted in hate crimes and murders since Sept. 11, 2001. Although I have helped chronicle hate crimes against the Sikh American community for more than a decade, I could not tell them.

Even as the White House, U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Bureau of Investigation express their commitment to protecting Sikh Americans in response to the massacre, there is one glaring problem with how the federal government monitors hate crimes against Sikhs in America: It doesn’t.

The FBI tracks all hate crimes on Form 1-699, the Hate Crime Incident Report. Statistics collected on this form allow law enforcement officials to analyze trends in hate crimes and allocate resources appropriately. But under the FBI’s current tracking system, there is no category for anti-Sikh hate crimes. The religious identity of the eight people shot in Oak Creek will not appear as a statistic in the FBI’s data collection. As a Sikh American who hears the rising fear and concerns in my community, I join the Sikh Coalition and Sikh American Legal Defense and Education Fund (SALDEF) in calling for the FBI to change its policy and track hate crimes against Sikhs.

It seems like a simple enough step. However, the FBI has not changed its policy, because it assumes that all hate crimes against Sikhs are motivated by anti-Muslim bias: this is both wrong and dangerous. It seems like a simple enough step. Contrary to popular framing, hate crimes against Sikhs are not a case of “mistaken identity.”

I believe it would not have mattered much to Wade Michael Page if he knew that the people he killed were Sikh rather than Muslim. From what we have gathered so far, Page is just like others who have targeted Sikhs in hate violence: they see people with dark skin, beards, and turbans as the enemy.

“Numerous reports have documented how those practicing the Sikh religion are often targeted for hate violence because of their religiously-mandated turbans – i.e., because of their Sikh identity, regardless of whether the attacker understands the victim to be Sikh or not,” said U.S. Rep. Joseph Crowley, a N.Y. Democrat, in a statement earlier this month. Along with six other lawmakers, Crowley introduced a resolution condemning hate crimes against Sikh Americans in the wake of the Wisconsin massacre; the resolution supports the community’s demand that the FBI track such crimes. This week, Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) also circulated a letter to her colleagues in the Senate, urging their support.

In the year after 9/11, the FBI reported a 1,600 percent increase in hate crimes against Muslims and those perceived to be Muslims. More than a decade after 9/11, violence against these communities is still a serious problem. In the FBI’s hate crimes statistics from 2010 – the latest year for which data has been released – anti-Muslim hate crimes rose by 50 percent from 2009 levels. But this data doesn’t give us specifics on how hate crimes impact Sikhs in particular.

Why does it matter? In order to marshal the resources necessary to prevent tragedies like the Oak Creek massacre from happening again, we need to understand the scope of the problem. In order to build strong working relationships with government agencies, elected officials and the media, we must demonstrate in numbers what we know in stories – that hate crimes against Sikhs is a real and ongoing threat.

“Given the tragedy in Oak Creek, we renew our call on the federal government to begin to track hate crimes against the Sikh community,” said Sapreet Kaur, executive director of the Sikh Coalition. “How can you address a problem you are not measuring?”

It’s not particularly burdensome for the FBI to create a distinct category for Sikhs. The Form 1-699 has distinct categories not just for anti-gay bias but also for anti-lesbian and anti-bisexual hate crimes. The FBI just needs to afford Sikhs the same dignity of being counted.

Sikhism is the fifth-largest organized religion in the world and more than half a million live in the U.S. Our faith was established in 1469 in present-day northern India and Pakistan. Our first teacher, Guru Nanak, called for devotion to One God, equality between all people, and a commitment to service. Like other religious people, many of us wear articles of faith, including long uncut hair, which men and some women wrap in a turban. Our turbans represent our community’s long-standing commitment to stand up and serve people around us, fighting injustice in all forms.

Nearly every person who wears a turban in America is Sikh.

Tragically, the turban has marked Sikhs as immediate targets during waves of anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim hate violence in America since 9/11 and long before. In a climate of gun violence, the tragic shootings in Milwaukee are the most recent chapter in this history. The time is now, more than ever, to track and respond to the problem.

To be sure, the FBI’s grouping different communities under “Muslim and those perceived to be Muslim” signals the emergence of a new racial category in America since 9/11 that can be called the “Muslim-looking other.” Many non-Muslim communities – Sikh Americans, Arab Christians, Latinos, and Native Americans for example – have been swept up into this new racial category. Communities that did not work together in the past banded together in the last decade to fight profiling and hate on all levels. That said, lumping all targeted groups into a “Muslim” catch-all category forecloses our ability to understand the specific needs of each group. Sikhs, in particular, happen to be the most visible targets in post-9/11 hate violence and deserve equal attention.

The federal government should fulfill the modest request of the Sikh Coalition and the greater community and begin tracking hate crimes against Sikhs.

The government can’t bring back the six people murdered in Oak Creek, Wis. But it can at least afford them the dignity of being counted.

You can sign the petition asking Congress to support tracking hate crimes against Sikhs here.

Valarie Kaur, an award-winning filmmaker, legal advocate, and interfaith organizer, is founding director of Groundswell, a multifaith initiative. Her documentary “Divided We Fall” is the first feature film on hate crimes against Sikh Americans after 9/11. You can follow her on Twitter at @valariekaur.

Ravieshwar Singh, a student at the Northwestern University School of Law who has conducted research on the perception of Sikhs in post 9/11 New York City, contributed to this piece.