He locked the washroom door, unravelled the nine-metre turban, took a pair of scissors and started cutting. Ten minutes later, three feet of hair lie in a pile and Charanbir Singh sat down and cried.

Outside, his parents and grandmother were in tears. Two friends persuaded him to come out, but Charanbir, his head wrapped in a towel, rushed to his room.

That was a year ago. Charanbir, now 17, still shudders at the memory. "I am very proud of my Sikh heritage and I never got my hair cut before ... but there were reasons. I had to cut my hair."

Sikhism dates back to 15th-century India. Adherents are required to not cut their hair, considered a visible testament to their connection with their creator. The turban was adopted to manage long hair and make Sikhs easily identifiable.

For many young men in Greater Toronto, that is the problem: They don't want to stand out.

Like other new or second-generation immigrants, many Sikh youngsters are desperate to fit in with the school crowd, while others complain of racism because they wear the turban. Add to that cultural influences, peer pressure and the desire to assimilate.

The end result? Many youngsters cut their hair, leading to family friction and, in some cases, lasting estrangement.

"Parents in the community often approach me, saying their son is insisting on cutting his hair," said Pardeep Singh Nagra, manager of employment equity with the Toronto District School Board, who is well known in the Sikh community.

"I try to play the role of the mediator," said Nagra, who keeps his hair long and wears a turban.

Nagra says both sides can be heartbroken, but adamant – the son believes the parents don't understand him, while parents are torn with his decision.

Nagra tries to help young people understand their religious heritage and the importance of practising their faith. "I tell them if they think life is tough (because of the turban), there may be something even tougher out there later on," he said.

Nagra also explains to the youths that their parents feel they've failed when children don't adopt religious traditions. But in the end, he says, the objective is to support the child.

"Although alienation, harassment and racism begin at the elementary school level, Sikh boys are in Grade 7 or 8 when their pain comes to the forefront," he said. "I think parents need to better help them navigate the discrimination by engaging their children at a younger age, and the Sikh community needs to be more proactive to engage the wider community and schools to be more attentive to these issues."

Some parents are open to discussing the turban's significance.

The topic was talked threadbare at Sandeep Chahal's Brampton home before his parents agreed.

The first-year engineering student at McMaster University in Hamilton says it was important for him to have their consent.

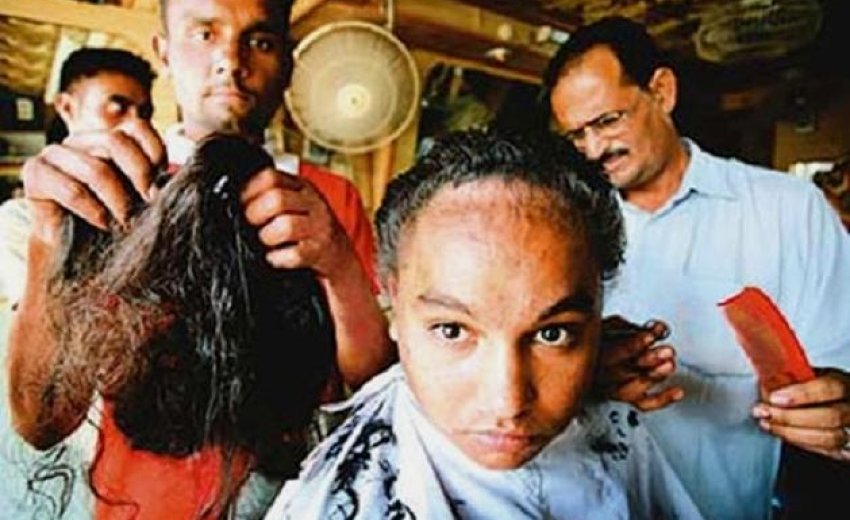

Eight months ago, Chahal, 18, got his waist-length hair cropped close to the scalp.

Chahal still feels strange without a colourful turban, but says he wanted to fit in. "I can't recall a particular incident where ... I felt like I didn't belong. But I obviously stood out."

But not everyone minds that.

Jashandeep Singh, 18, a commerce student and Chahal's roommate at McMaster, wears a turban. "I have my moments when I want to get (a haircut) but I'm religious and I also realize how important this is for me," said Singh, whose family lives in Brampton.

He is often asked about it by curious strangers. "I explain as best I can why it's important," he said.

The dwindling number of turban-wearers bothers Nagra, but working with young people, he understands the pressures they face.

Not everyone does.

When a 19-year-old York university student, who doesn't want to be named, was younger, he told his parents he wanted to cut his hair. His father beat him with a belt, he wrote in an email to the Star. But tired of continuing harassment at school – he was called names and even beaten up – he got his hair cut.

"And as a result, I was thrown out of the house and disowned."

His parents have not contacted him since. "I still don't know if my parents remember me or think about me," said the student. "But then again, they were right on their part and I was on mine."

Sikh fathers say their sons make them proud when they wear the turban. "Of course," said Bhupinder Singh, Charanbir's father.

"But I can't disown him if he doesn't," he added in Punjabi.

When Charanbir first said he wanted to cut his hair, his father took him aside and asked if he was having trouble at school.

"He said no, but I knew there was more to it." Singh explained the significance of the turban and hoped for the best.

Months later, when his son shut himself in the washroom and cut his hair, Singh said he wasn't angry. "I was just very, very sad. I tried to understand (him). I didn't go to school in Canada so I don't know how tough it can be ... But I do wish he still wore the turban."

Stories like these are common, says Birinder Ahluwalia, owner of BSA Diagnostics Clinics in Scarborough and North York.

"It's an awful feeling," said Ahluwalia, who wore a turban when he immigrated to Canada in 1985. But within the year, he decided to cut his hair. "No, I didn't feel any racism, but (I) got strange looks of surprise from people."

Telling his father in India about the decision was difficult, said Ahluwalia, 53. "When I told him, he was quiet for about 30 seconds. It felt like the longest time," he said.

Ahluwalia felt awful for a long time after having his hair cut. Now, 24 years later, he is thinking of growing his hair and wearing a turban.

"It's one of those things you never truly get over," he said.