Introduction

The Sikh nation today is in difficult times. The Sikh community which once was a beacon of humanity and inspiration for the world, today is a community much like any other. Alcoholism, spousal abuse, and drug addiction drag down this nation like every other, or even worse.

Three hundred years ago, Guru Gobind Singh, the founder of the Khalsa, sang the praises of his greatest creation, the Order of saint-soldiers, but also warned that should they take up the way of mindless rituals and give up their distinctiveness, he would abandon them. Today, as a fulfilment of his warning, the main preoccupation of Gurdwaras is the performance of rituals. Guru Granth Sahib is treated like an idol and ritual readings take place around the clock. Sikhs everywhere are complicit in this practice.

In describing the vitality of the Sikh nation in the present day, inventor and philanthropist Narinder Singh Kapany recently pointed to its growing numbers, the increasing quantity of Gurdwaras, the number of members in status-carrying jobs, and the array of schools and universities with programs that study Sikh dharma. This view is widely shared, using worldly criteria to measure the prosperity of the Sikh community.

Another, opposing view is to judge the well-being of the global Sikh nation by its success in living by and sharing the inspiration of the Guru. Originally, the vitality of the Sikh community emanated from the practice of deep meditation, perfected and taught by the Guru. This practice was passed from Guru Nanak to Guru Angad and so on, unto the Khalsa. Children as young as five could achieve profound meditation and the mother played the unique role of Gurdev Mata, the first spiritual teacher of the newborn. The historic Guru's mothers, wives, widows, and daughters - and through them, all Sikh women - enjoyed a personal connection with the great teacher and leader of the Sikhs. All this unraveled in the 1700s and 1800s. In the mid-1700s, with the Sikh nation under threat, deep meditation gave way to martial exercises and everywhere, grown men came to predominate. With the passing of the guruship to Siri Guru Granth Sahib, both the care of the Guru and the transcription of new volumes was entrusted to men only.

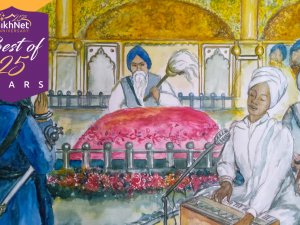

The years of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's rule in Punjab, witnessed a decline in the spiritual legacy of Guru Nanak. While temples were lavishly renovated and decorated, the Brahmanical rituals Guru Gobind Singh had warned of took hold in the maharaja's court. In place of meditation, alcohol lubricated the affairs of state. In place of the high status and dignity women had enjoyed in a previous time, women were bought and sold in Ludhiana, prostitution prevailed in Amritsar, and female singers and dancers provided entertainment for the maharaja and his male guests.

With the spirit of Khalsa so compromised for so long, it should have surprised no one when the traitor Lal Singh decided the Anglo-Sikh War and the fate of Punjab for the foreigners. It should also have been no surprise that the young Dalip Singh, heir to the maharaja's throne, was no spiritual prince. Coddled and sheltered from the world, he had not been educated in the Guru's wisdom, to say nothing of ruling a kingdom.

In their colonial enterprise, the impressive British and their missionaries continued what Sikhs had already begun, further diluting and polluting their faith. While some Sikhs held back, others enthusiastically enrolled in British schools, joined the imperial army and civil service, and unconsciously picked up the tastes and habits of the conquerors.

The series of articles of which this is an introduction first took the form of a presentation given by the author at the International Sikh Research Conference at the University of Warwick in June 2017. It is intended as a wake-up call from the slumber of rituals, of religion for hire, and shallow representations of what is a uniquely inspiring and timely legacy at its root. In these articles is a case study which it is hoped may convey the reality that children are not dumb passengers on the journey of spirituality. Rather, as Guru Harkrishan illustrated so well, children are fully capable of understanding and embodying the very best of human potential and possibility if only given a chance.

There are also a number of recommendations to help lift the Sikh nation out of the spiritual quagmire in which it finds itself today. There are recommendations on: spiritual training and education of the young, religious practice, spiritual culture, self-concept, spiritual sovereignty, and outreach. It is a long road from addiction and abuse, and a self-concept which is increasingly ethnic, to the glory of a sovereign, spiritual nation. But it is a road, in my view, that must be begun for the love of Guru, and must be begun now.

Read Part 2 of this series here.