The traffic noise from the flyover outside the window was deafening and I could barely hear what Baljit Singh Brar was saying. Brar edits Jalandhar’s Aaj Di Awaz newspaper, aptly named, amid the din. “Where is Bhindranwale’s son?” I had to shout. He pointed at the man sitting quietly at the corner of his desk.

So this was the elder of the two sons of India’s most dreaded “separatist leader” from a quarter century ago. Light brown eyes, five foot ten, tight black turban, flowing salt-and-pepper beard, ready smile, his two cellphones blinking. Ishar Singh looked like your friendly neighbourhood realtor, somebody you could trust enough to buy your house from.

That is exactly what Ishar Singh does for a living. He buys and sells property just 80 kilometres from the Sikhs’ most violent and traumatic battle in centuries, if you do not include the savagery of India’s partition in 1947. Ishar Singh is 37, the same age his father was the night he was killed in the devastated Akal Takht after the army sent tanks into the parikrama of the Golden Temple. “My father died four days after his birthday,” Ishar said.

Ishar Singh is 37, the same age his father was the night he was killed in the devastated Akal Takht after the army sent tanks into the parikrama of the Golden Temple. “My father died four days after his birthday,” Ishar said.

“I am very, very proud of him,” says Ishar of his father. “I can never be bigger than him. I cannot add to his name, only reduce it.”

He remembers that an uncle, a subedar in the army, identified the body. It took the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee and the Akal Takht nearly two decades to acknowledge that Bhindranwale was dead. On June 6, 2003, Ishar Singh was honoured with a siropa at the Golden Temple, watched by an assortment of old Khalistani diehards like Jagjit Singh Chohan and Wassan Singh Zaffarwal. Matters had been delayed because Bhindranwale’s successor at the Damdami Taksal, Baba Thakkar Singh, had persisted in proclaiming that the Sant was not dead, would reappear one day, and lead the Sikhs to glory. Every year now, Ishar Singh dutifully turns up at the Golden Temple for a memorial for his father on June 6, the anniversary of the climactic Bluestar battle. The Akal Takht organises an akhand path of the Guru Granth Sahib.

There is a certain morbid fascination with the families of history’s most infamous characters. What were the wives and children like? What did they come to? Were those men good husbands and fathers? So we know about Hitler and Eva Braun (no offspring); Saddam Hussein (wife and two daughters in exile in Jordan, both sons dead, both sons-in-law killed on Saddam’s orders); Velupillai Prabhakaran (killed with older son in final ltte battle, wife, daughter and younger son dead in separate battle). What about Bhindranwale?

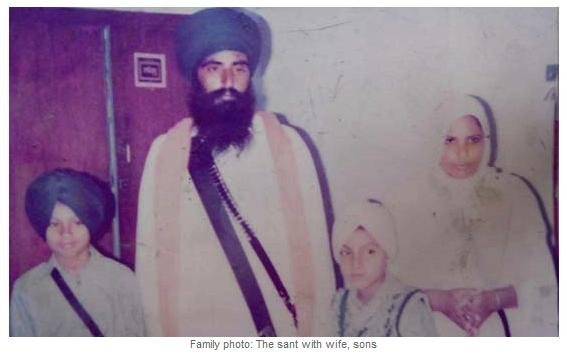

Ishar was just five years old when Jarnail Singh Brar was anointed the 12th jathedar of the Damdami Taksal. He left home and adopted the name “Bhindranwale” after the village of Bhindran Kalan where the sect was originally located. “After that we only saw our father at his satsangs,” Ishar said. “But we were well looked after.” Did he miss his father? “From the family point of view I was sad, but from a Sikh point of view I was very happy.” The Jalandhar editor waved a laminated family photograph at me—a very young Ishar Singh with his eyes shut, an oddly self-conscious Sant Bhindranwale, his younger son Inderjit, his wife Pritam Kaur.

When he was 10, Ishar Singh was sent to study Gurbani under Mahant Jagir Singh at Akhara village near Jagraon. Immediately after Operation Bluestar, Pritam Kaur moved with her young sons to her brother’s home in Bilaspur village in Moga district.

Ishar does not have his father’s piercing gaze. He has a good sense of humour, but not the earthy wit that Jarnail Singh flashed as he held court on the rooftop of the Guru Nanak Niwas in Amritsar. Ordinary folk tiptoed into a meeting with him. There was always a hint of menace, helped by the young men lounging nearby with their rifles.

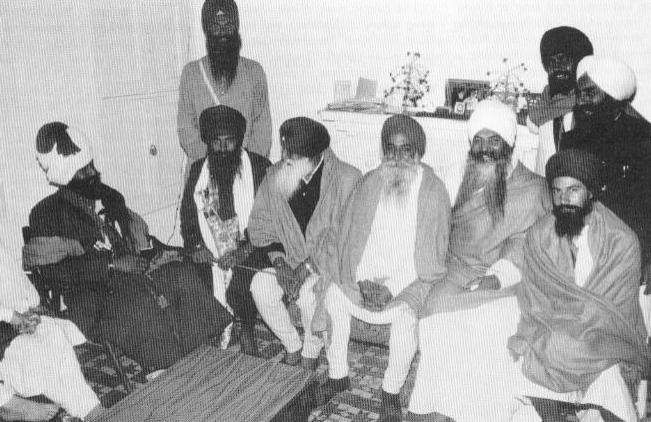

Gurcharan Singh Tohra - SGPC President, Gurdial Singh Ajnoha - Akal Takhat Jathedar,

Yogi Harbhajan Singh, Bhai Amrik Singh - All India Sikh Students Federation President

“I was detained for two days by the police in 1988 and tortured,” Ishar says, “but they had to let me go.” He was a good student, and stood first in his Class 10 examination in Sangrur district, winning a scholarship for the final two years of his matriculation. But just then, in 1991, he married Amandeep Kaur, whose father Joginder Singh perished with Bhindranwale in the fighting at the Golden Temple. Ishar never went to university. “My wife completed her BA,” he says proudly. He himself became a dairy farmer, and grew two crops, kank (wheat) and jhona (rice) on the family land.

“Many people offered to help us,” Ishar said. “We were never in need. My father did everything for the people, and they loved him.”

What had his father left him, besides the name? “What more can he give me?” Ishar said. “I’m very, very proud of him. I can never be bigger than him. I can’t add to his name, only reduce it.”

Ishar Singh does not believe his father ever preached violence. Could he begin to imagine the tension in Punjab in the early 1980s, Bhindranwale’s defiant, gun-toting drive through Delhi, the skirmishes on the periphery of the Golden Temple, the drive-by shootings of innocent civilians in Delhi, the assassinations of prominent opponents, and the terror in the air?

“My father never threatened, he only replied (to threats),” Ishar Singh said in the Jalandhar office. “He was accused of ordering the deaths of 70 Hindus for every dead Sikh. He was misquoted. Bal Thackeray had said India has 70 crore Hindus and two crore Sikhs and there are 35 Hindus to every Sikh. The Tenth Guru (Gobind Singh) had said each Khalsa can fight 1,25,000 enemies. My father only said each Khalsa can take on 70 enemies, and this was distorted.”

Whatever the ratio, I remember a tense journey in a state transport bus from Amritsar to Delhi in early 1984. The Sikh passengers were clustered near the driver, and the Hindu passengers were huddled in the rear. Nobody spoke. Only when the bus reached Ambala, and Punjab was behind us, did everybody relax. Today Punjab’s highways are four-lane and traffic moves at high speed, save for the occasional tractor or the farmer with his wife riding pillion. Sometimes Bluestar seems 25 light years away.

So were Ishar Singh, his brother and his mother content with anonymity after the carnage of 1984 in Punjab and Delhi? Both he and Inderjit applied for passports, he said, and were turned down. “But you know how it is in India. Somebody pulled strings and we got our passports.” Inderjit emigrated to Canada in 1999; Ishar is reticent about where his brother works. A plastic factory, is all he will say. He himself has travelled to Britain, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

On the outskirts of Toronto, a gurudwara sports a large portrait of Bhindranwale on its gate. The dreams of Khalistan linger among the diaspora. Bhindranwale is alive and well on YouTube, where you can watch him make his straight-from-the-holster speeches. He has a Facebook fan group, and is a “trending topic” on Twitter.

On the outskirts of Toronto, a gurudwara sports a large portrait of Bhindranwale on its gate. The dreams of Khalistan linger among the diaspora. Bhindranwale is alive and well on YouTube, where you can watch him make his straight-from-the-holster speeches. He has a Facebook fan group, and is a “trending topic” on Twitter.

“In England, small children used to say to me, can I touch you?” Ishar said with a smile. “My father did not become so popular in one day. There are seven or eight thousand sants in Punjab. Why are you asking me only about him?” Brar, the editor, jumped in to say younger Sikhs were admirers of Bhindranwale. “You should see the number of cars with Santji’s pictures on the dashboard,” he said. “There are Bhindranwale ringtones. Many gurudwaras perform ardas for him regularly.”

Ishar said his father never believed in politics, only in dharma. “Politics is based on deception, religion on morals,” he said. So how did he reconcile this with his own work as a property dealer, where so much black money is sloshing around? His reply was elliptical. “The government wants 45 lakh rupees to convert one acre to residential use,” he said. “How can this be honest?”

We were meeting on the eve of Gandhi Jayanti. Did he think Gandhi.... Ishar did not let me complete my question. “Don’t talk about Gandhi,” he said. “He betrayed the Sikhs in 1947.” And Brar the editor said, “Whenever we talk about a weakling, we call him ‘Gandhi’.” Ishar Singh laughed heartily, his eyes shining.

What about his own children? Ishar Singh spoke proudly about his daughter Jeevanjyot, who is 16. She studied “non-medical” subjects like physics, chemistry and mathematics, he said. What did she want to be? An interior designer, he said. That would be a lucrative choice, I said. He laughed again, in agreement. His son Gurkanwar is 13 and he does not know where his life will lead.

As we parted, Ishar Singh said, very much the realtor: “Tell me if you need a car. I have two or three. I can arrange anything. People are always prepared to help me.” We agreed to meet the following day at the Golden Temple for pictures.

The next morning Ishar Singh came to the Golden Temple with Bhai Ajaib Singh, an old associate of his father’s. Ajaib Singh said Ishar was the president of the Sant Kartar Singh Educational Trust, which runs two schools and a hospital in and near

Mehta Chowk where the Damdami Taksal is headquartered. A tall Sikh in traditional attire was walking down the jute matting atop the marble parikrama, and both Ishar Singh and his companion stooped to touch his feet. “That was Giani Jaswinder Singh, the head granthi of the Harmandir Sahib,” Ishar said.

The Harmandir Sahib looked as glorious in the sunshine as it did 25 years ago. The Akal Takht, blackened and pocked by tank shells and heavy gunfire during the bloody fighting, had been restored to its old splendour. At the rear rose rows of whitewashed rooms where pilgrims could speed up the long waiting lists of akhand paths. The government has acquired land around the temple and landscaped it, except in the front where old shops still stand cheek by jowl, doomed to be moved soon. The quiet and peace was punctuated only by the shabad kirtan broadcast round the clock from the inner sanctum.

The Harmandir Sahib looked as glorious in the sunshine as it did 25 years ago. The Akal Takht, blackened and pocked by tank shells and heavy gunfire during the bloody fighting, had been restored to its old splendour. At the rear rose rows of whitewashed rooms where pilgrims could speed up the long waiting lists of akhand paths. The government has acquired land around the temple and landscaped it, except in the front where old shops still stand cheek by jowl, doomed to be moved soon. The quiet and peace was punctuated only by the shabad kirtan broadcast round the clock from the inner sanctum.

Thousands of people hurried about their devotions, oblivious of Ishar Singh as he posed for the photographer. Nobody came up to him in awe or reverence. He wore a saffron turban on this day, and he looked like just another pilgrim come to pay his respects.

Waiting to bid him farewell, I watched while Ishar Singh fiddled with one of his two cellphones, standing still among the milling worshippers. He appeared to be looking for something. Finally he said, “I want to show you something. Let’s move to the shade in the portico.” There, he proudly held out a picture on his phone. “My family,” he said. “That’s me, my wife, my son, my daughter.”

(The author, an award-winning journalist, covered the events in Punjab for Reuters in the 1980s.)