My fingers are trembling as I dial his number. I had promised him that I would call him in Punjab once I returned to the U.S.A. It would be perfect timing; he would be out of the Centre by then.

My fingers are trembling as I dial his number. I had promised him that I would call him in Punjab once I returned to the U.S.A. It would be perfect timing; he would be out of the Centre by then.

An entire month has passed following my return before I gather the courage to call Mahinder.

Of all the people at the Centre I had met, I had connected with him the most. Perhaps because he was a repeat. Perhaps, because I had successfully negotiated a huge redemption from him. He had promised me that, to every extent possible, he would undo his wrong-doings. We spent a good 3 hours talking ... and not a day has passed by since then that I don't think of Mahinder and his promise.

Today my expectations are flying high as I hold the phone, hoping to hear his voice - healthy, fighting the drug war, redeeming the hundreds of others in his district to which he introduced Smack/ heroin, that white angel of death. The odds were against hope that Mahinder had managed to succeed in keeping his promise; maybe that is why I had delayed making the phone call until this morning.

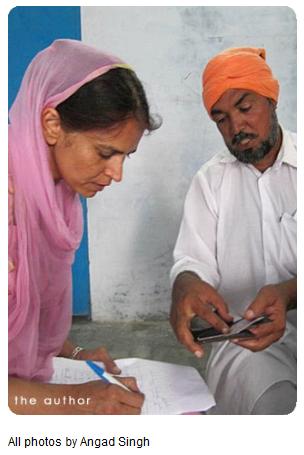

During my trip to Punjab this past summer, Dr. Balwant Singh Sekhon arranged for my teenage son, Angad Singh and I to visit the Akal De-addiction Center at Cheema in district Sangrur, Punjab.

"Biba Ji," he said to me, "you should visit and write about the drug issue in Punjab". Much has already been written about it I thought, what new information or perspective could I have to offer?

As I travelled on the road from Muktsar to Cheema, I did not realize that what was going to come out of this visit was not a story or a report but rather new bonds and connections of hearts. After our visit, as we returned to Muktsar, all Angad and I could talk about was our drowning brothers. We felt powerless to change a thing in their lives but the visit had surely changed us.

We prayed that they saw and understood the message in our sad parting eyes - "Please be well, our brothers; our nation needs you". Bustling with devotional energy centered around the Gurdwara marking the janam asthan (birth place) of Sant Attar Singh Ji of Mastuana, Cheema is also a home to one of the oldest Akal Academies that is fighting the drug war at the grass roots level by instilling value based education and responsibility in the local youth. It is mind-blowing to see the ‘Desi Sharab Thekas' (Government licensed country alcohol shops) share the same street as the gurdwara and the academies not too far away from each other.

Bustling with devotional energy centered around the Gurdwara marking the janam asthan (birth place) of Sant Attar Singh Ji of Mastuana, Cheema is also a home to one of the oldest Akal Academies that is fighting the drug war at the grass roots level by instilling value based education and responsibility in the local youth. It is mind-blowing to see the ‘Desi Sharab Thekas' (Government licensed country alcohol shops) share the same street as the gurdwara and the academies not too far away from each other.

A silent war that the two opposing institutions have declared against each other; with the Akal De-addiction Centre as the DMZ (the Demilitarized Zone) where the two make peace with each other.

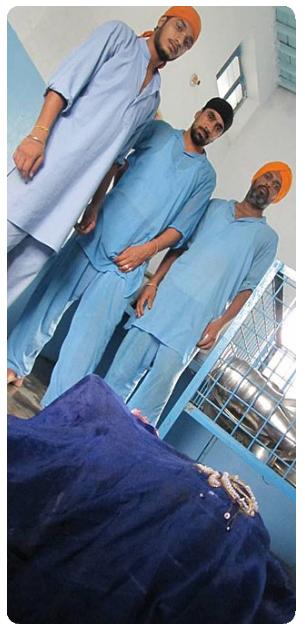

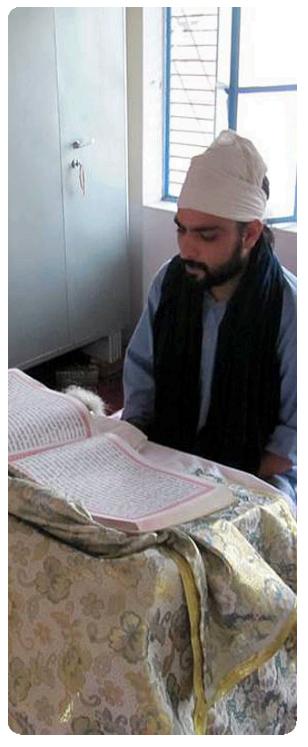

Complete with iron bars, armed Security guards and supervisory staff, the center gave us a nervous thrill; we had no idea what to expect when we entered. Whereas the vacant staring eyes of some of the inmates from within locked cells intimidated us, the sight and sounds of a recovering addict reciting from the Guru Granth Sahib in an adjacent room calmed our fears and put us to ease.

This experience marked my first encounter with drug addicts, some of whom were criminals in addition to their addiction. I had no idea about what I was going to write or whether any of them would even agree to speak with us.

In Angad Singh, I had the perfect helper. He quickly mingled, making the patients laugh with his awkward ways and accented Punjabi. In no time they were friendly and ready to share their stories. It was evident in their eyes that they begged only for acknowledgment in return and appreciation of the fact that they had taken steps toward bettering their lives ... bold steps indeed.

The hope I saw in their eyes was calming yet painful. I was told that even though this center has a high success rate, close to a quarter of them would relapse and, when they did, it would be far worse than before. A lot of the men were on a quick road to death as the 42-day program at the center came to an end.

The well qualified Dr. Sanjeev Kumar, the Medical Officer In-charge of the Centre first told us about their operations and activities, followed by an in-depth expose on the drug issue in Punjab, including demographics, causes, cures, social and anatomical effects, and more.

We were not only impressed with his knowledge, but the purity of his intentions to help this worthwhile cause clearly came through. When asked what promotes such an incredible success rate for the program, he summed it up simply yet powerfully by answering: "Spirituality, of course". In addition to the Government mandated protocol, the center heavily supplements daily diet and exercise with an ayurvedic regimen designed to restore organ damage such as that of the kidneys, liver and lungs which tends to be common among substance abusers. There is individual, group, and family counselling service supervised by specialized psychologists.

In addition to the Government mandated protocol, the center heavily supplements daily diet and exercise with an ayurvedic regimen designed to restore organ damage such as that of the kidneys, liver and lungs which tends to be common among substance abusers. There is individual, group, and family counselling service supervised by specialized psychologists.

"The real edge is provided by catharsis that takes place through meditation and reflection. We have a full gurbani-based regimen that inspires the inmates towards introspection and committed action," Dr. Sanjeev Kumar explained.

Baldev Singh - 45 years old, from Cheema - who now volunteers at the local gurdwara, testifies to the fact. He comes down every so often to motivate other patients; it was a joy to meet with the man responsible for many of the success stories. Ever since he has been drug free, the opportunity to contribute his time at the gurdwara and to counsel other patients at the Akal De-addiction Center has created a sense of sanctuary for Baldev.

"Success on the Edge" is what he calls his case. A Punjabi farmer following several generations before him, Baldev became addicted in his early 20's. The person who introduced him to opium was none other than his grandfather.

It is common for farmers and labourers in the region to use any of the easily available drugs (poppy husk, opium, even a tobacco and alcohol combination) for increased performance in the fields. At first it wasn't bad; he got married and had a child. But as it started getting worse, life became a living hell. He became unable to farm. He would steal family money and his married life soon became marred in daily quarrels. He started taking refuge in alcohol at night. The need for opium to rid of alcohol hangovers intensified and one day he found himself lifeless and near death.

It was then he was brought to the Centre, some three years ago. He rebelled by running away within the first three weeks. It was no surprise that he relapsed. His second admission was voluntary in May of 2008, at the invitation of a recovered alcoholic; this time it seems to have worked.

"This whole year has been very peaceful. No police cases, no family quarrels, more money for the necessities", he explains. Yet, Baldev is not a worry-free man. His son is 16 years old and during the time Baldev was in and out of prisons and rehab centres, his son dropped out of school. Baldev constantly worries about the dark shadows that surround both him and his son, waiting to pounce on them at a weak moment.

The land Baldev worked on was contracted out by his brothers for the period in which he was away and although there is income to get by, there is no real purpose in life for him other than acting as a watch dog protecting his son. "That's why I call my situation a ‘success story on the edge‘. Getting hooked on drugs is a sure death warrant", he told me. "If you do drugs, they will eventually kill you; and until you quit for good, you experience death over and over".

"That's why I call my situation a ‘success story on the edge‘. Getting hooked on drugs is a sure death warrant", he told me. "If you do drugs, they will eventually kill you; and until you quit for good, you experience death over and over".

I have hope that Baldev will be okay but I wasn't so sure about Sarab from Delhi who was a successful business man until he found himself in a repeat of a drunken violent rage, beating his wife and children and getting into trouble with the law. The guilt on his face was clear and pleading.

"All I want to do is get better and get my family back. Do you know my son is about your son's age and I almost killed him?" he asked me with tears in his eyes.

Whereas poppy husk (bhukki), tobacco (tambaku), opium (afeem) and smack (charas) engulf Punjabi villages especially those of the working farmers, the very legal weapon of mass destruction, alcohol, is silently drowning the lives of the elite as well.

Alcohol consumption has become a very acceptable thing in Punjabi circles and as the business man Sarab says, what are the chances he will not relapse? How long can he stay away from alcohol, I wondered. Close to half the addicts in the Centre are abusers of two perfectly legal substances - alcohol and tobacco.

When Mahinder said that tobacco was the first thing he got hooked to, I posed an obvious question: "Since when did it become acceptable for Sikhs to chew tobacco"?

"Ever since it became acceptable for them to gulp alcohol!" my teenage assistant interrupted me.

If alcohol and tobacco are easily available at every corner in Punjab, smack and opium are not far away and nearly as easy to obtain.

Shockingly, Mahinder's latest smack supplier is a elderly woman from his village and, with the assistance of Mahinder's family, I was able to speak with her. She reiterated the question when reminded of the ethical values. "When everybody from the Ministers in India to the local contractor draw their salaries off of the "thekas" (alcohol shops), why can't I provide for my family with a few poorries (packets) of charas?" she countered, "what's the difference, Bibi? They both kill".

I had no answer for her.

There are other legal options for the more sophisticated. A trend among young college-bound boys and girls finds the use of synthetic derivatives of opium which are much cheaper, easily available at both chemist shops and drug peddlers. Morphine is also readily available without prescription. Lomotil (Di-phenoxlylate) has the same effect as opium and is legally available everywhere.

It takes only seven days to get addicted. Just as with opium and heroin, side-effects including headaches, palpitations, restlessness, loss of appetite, mood swings, aggressiveness, and diarrhea will become increasingly severe until more of the drug is consumed.

The Akal De-addiction Centre sees all kinds of addictions in all ages and education levels. Since it serves mostly the rural population, the Centre's patients comprise mostly males. Just in the month of June during our visit, the Centre admitted 39 men of varios ages. The popularity of the Centre with its affordable cost and high success rate approaching 80% has driven growth (primarily through word-of-mouth) beyond its intended capacity. However, since there are minimal rehabilitation services at the Centre, many patients succumb back to their old debilitating lifestyle as they return to the same environment and influences that reclaim them faster than any follow-up volunteer from the center is able to.

Dr. Sanjeev Kumar attributes the reason for drug prevalence in Punjab to many factors such as peer pressure, easy availability, pleasure seeking attitude, elevated workloads, inability to deal with social issues, but he does not deny that political reasons such as high unemployment rate and post 1984 blues have played a big role.

"Ultimately, it all comes down to money", he says, "alcohol and the drug business are the easiest ways to get rich". The profits are very attractive and the risks in peddling are few. One poorrie of smack can be purchased for Rs. 20 (40 cents U.S.) in Delhi. It is so easily accessible that the villagers make routine trips to get them. They then resell the poorries for Rs.100 ($ U.S. 2.00)each. Payments as little as 10K/year in bribes to officials ensure the traffickers can go about their business uninterrupted.

This desire to get rich quick got young Mahinder into drug dealing, but before long the money fizzled out in court cases and treatment centers. I wondered how his wife and children were handling it all.

So here I was at my home in the U.S.A., making the call I told him I would. My heart was beating fast in anticipation.

After a couple of rings, the phone was answered with a burst of enthusiasm at his home in Mansa. I introduced myself to his mother who then handed the phone to Preeti, Mahinder's wife.

She started as if she had always known me and was waiting for the call; I too felt surprisingly close to her. "He said you'd call ... He spoke about you and the promise he made. He was so excited when he got back from the Centre. The Centre did a really good job. His health improved much, his complexion ... like it used to be ..."

I was relieved to hear it all and now I wanted to hear his voice even more. But her voice seemed like she wanted to cling to me and never let go of the call, so I just listened as I tried to picture her on the other end; a beautiful young woman, educated and intelligent. I recalled how Mahinder had a spark in his eyes when he spoke about his beloved and how they were madly in love with each other and got married without the families' consent.

A handsome national level soccer player studying Physical Education in college, Mahinder couldn't wait to return to her in Punjab and marry her as he finished his degree at the University of Nagpur. Sadly, by the time he was finishing college, he was already hooked on tobacco; smack was not far behind, introduced to him by his ‘friends'. He was in the early stages then, and she suspected as much, even before they married.

But she was in love. Shortly after their marriage, he and a friend introduced hundreds if not thousands in the Mansa district to smack. Mahinder made a lot of money. He wanted to give her the best.

"He said he wanted to help other addicts. He came back with a mission but then one evening his friend called him ... That's all it took! Sister, maybe you can bring him back! Please, call him! He is in a Centre in Mullanpur at this number. He'll listen to you ... you never know what will bring him back ... Please!" she pleaded persistently.

The trembling in my fingers spread to the rest of the body. My throat parched and it seemed to take all my strength to hold the phone to my ear.

Her voice told me she was still in love with him, so desperate to have him back. Taking care of his parents, their children and dealing with his addiction, treatments and remissions, she embodies a typical Punjabi woman's life; her only dream and aspiration is to get her husband back from this death trap.

"We have not left any center in Punjab - Mohali, Chandigarh, Bathinda, Patiala, Cheema ... he has been everywhere. This time it was extremely severe because he did 20 bits of smack, all at once. He fell unconscious, turned white and his eyes rolled over. I thought I had lost him ... but he is alive and I am not giving up. Please tell him that his family needs him ... Will you?" she begged.

I could hear her children of seven and four years screaming in the background, hoping it was their father on the phone and wanting to talk to him. She eventually fell silent, not sure if I was still on the other end. The quite moments felt heavy as if the whole family had suspended their lives in a hope to get him back, to will him back - the one who had slipped yet again to even deeper depths and they hoped a stranger far away had some kind of power to help.

"You cannot rest until you help all those people you caused to become addicted to smack", I had said when we were saying our good byes at the Centre, and he had agreed. Perhaps the redemption I had negotiated with him was too heavy for him to bear. Perhaps, he was only serving his destiny ...

I did not have the strength to call the other two numbers.

[The Akal Charitable De-addiction Centre is a non-profit center run by the Kalgidhar Society (www.barusahib.org). Any substance abuser with a positive identification is eligible for treatment. The Center can be reached by calling (91)-1676-284272.] The names of the patients have been changed to protect their privacy.