Can you tell us some about yourself and your background?

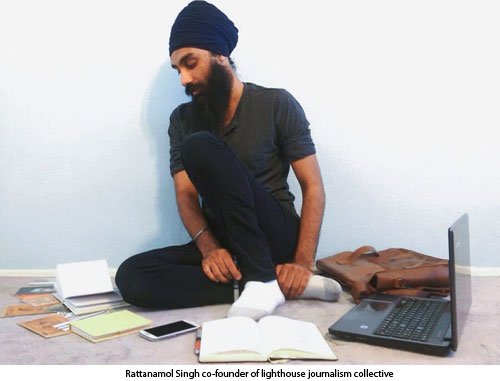

Fateh, my name is Rattanamol Singh. Recently, some friends and I started a journalism collective, Lighthouse, to tell stories that we wanted to pursue through the mediums (writing/film/tech) that we like working with. Since graduating from school, I’ve been fortunate to encounter some of the most interesting and intriguing global situations. These have forced me to question most of my rooted assumptions and continually interrogate how I look at the world. Over time, there seemed a pattern - the most important stories I kept on running into were ignored. So Lighthouse is an experiment. My friends and I get to put out a lot of what we’re working on, while also experimenting and creating new types of media.

Fateh, my name is Rattanamol Singh. Recently, some friends and I started a journalism collective, Lighthouse, to tell stories that we wanted to pursue through the mediums (writing/film/tech) that we like working with. Since graduating from school, I’ve been fortunate to encounter some of the most interesting and intriguing global situations. These have forced me to question most of my rooted assumptions and continually interrogate how I look at the world. Over time, there seemed a pattern - the most important stories I kept on running into were ignored. So Lighthouse is an experiment. My friends and I get to put out a lot of what we’re working on, while also experimenting and creating new types of media.

Our first release is a written narrative that follows the 1980s Sikh Insurgency through the eyes of General Labh Singh’s wife, Devinder Kaur.

What inspired you to take on the project of writing 'Labh'?

With Lighthouse, one of our goals is to use narrative journalism to tell countermemories, stories that challenge accepted, popular history. When we first came across the story of General Labh Singh, it seemed like a natural fit. At first, my reaction was -- A General? What the hell? How do you become one? What does this even mean? There was a certain allure to him, but we weren’t sure why.

Our interviews with his wife, Devinder Kaur, became a start in exploring both their lives and the larger Sikh resistance. There were these scenes that continued to jump out. The Battle of Amritsar. The Prison Breakout. The Missions. The Bank Robbery (not amateur hour either, but the largest bank robbery in Asian history). So it was clear - he was one of the most important figures of 1980s Punjab and involved with the most significant events and peoples of the decade.

A couple things were immediately evident. First, there was a boldness to each action of the resistance. Second, these stories were very different than the history that’s been put forth by the Indian state for the past 20/30 years. Here, we had a band of youngsters (our age, often younger) taking on the entire military and political might of one of the world’s most powerful countries. Yet their narratives had rarely been shared in any meaningful manner. The result was a vacuum where the government’s presentation of facts had won out. This meant the actual voices of the Punjab, people like General Labh Singh and Devinder Kaur, were sidelined.

So the inspiration for us was pretty clear - could we begin the process of crafting a narrative that recreated the universe of 1980s Punjab. Then, could this process be used to take on the official presentation of history? In doing so, perhaps we could also begin creating the foundation of narrative journalism within a Sikh space.

What did you learn during the process of writing 'Labh'?

We learned early on that beyond everything else, Labh was an intimate tale.

We learned early on that beyond everything else, Labh was an intimate tale.

Love. Life. Family. Struggle.

We had gone in intent on understanding how an insurgency works at a political level, but in reality, the reason the government’s narrative had been so successful is because they were able to completely depersonalize the movement. This insurgency was the war of the normal folk of the state and the government’s presentation of history took ownership of this rebellion away from them.

It’s brilliant really. Take away the hopes, fears, longings of a people and you can craft whatever you want the world to believe.

We realized these characters were normal, imperfect individuals. Each was different and had their own dreams and insecurities. They were motivated by different things and they rationalized their actions in their own ways. They were farmers, students, police officers, who moonlighted as romantics, dreamers, revolutionaries. When it was necessary, they acted upon these values and become the personal powder kegs for a revolution.

This is what we realized had been taken from them. The government presented a geopolitical tale and rendered them as nameless militants. In this systematic process of dehumanization, survivors and resisters like Devinder Kaur were removed from the public space and the memories of those like her husband were tarnished.

The magnitude of this framing is so unreal. The way it’s been successful is scary. Many of our people are terrified to address the movement. Instead it’s rationalized as, “We, Sikhs, asked for it. What else did you think would happen if we took up weapons? This was just a government trying to protect itself.”

In listening to Devinder Kaur, we realized our sole purpose was to tell these stories. It wasn’t our job to arbitrate the rights and wrongs of these individuals, but simply to tell their what and how. These characters had taken it upon themselves to become the custodians of their people’s rebellion, so all we had to do was simply ask, why.

Why’d Harjinder Singh Jinda, the kite flying, carefree phuratila, ride off and create a personal mandate to take out the politicians and generals who he felt committed genocide against his people. Why’d a young city girl leave the comfort of her parents’ home and finds solace in a movement her class and position rejected? What led, Labh Singh, a police officer from Amritsar, to go to Darbar Sahib and be instilled with something that eventually turned him into a General of his people's rebellion.

In searching for why, our hope was that the aims, fears and aspirations of these individuals could be reconstructed.

Was there anything that struck you as you spoke to Devinder Kaur, a woman who had been through so much?

There are moments you notice in the middle of conversations. Of definite defiantness. Resolve. A sense of chardikala, perhaps?

Much of her life has been lived in the memory of her husband (walking into the house, the first thing you notice is his shaheed picture in the living room). Still, over the past 20 years, she’s raised her children while living and working in New York. So it becomes a very immigrant tale of survival and you’re stuck with the realization that she represents more than herself. She wasn’t just a female survivor of war but a everywoman of the Punjab. Her life was a life swept up by the turmoil occurring around her. The same thing that happened to thousands of others. I think we forget that sometimes. How much war actually impacts a person. Yet, at that instance, her unapologetic resolve makes you think about why all of it seemed so necessary for those fighting it.

What would be the best outcome you could see from Labh?

I’d love a more critical look at the worlds around us, and within the Sikh space, a more open look at this movement. At some point, there has to be a focus on articulating independent, countermemories of our own. Why do we accept the narration of events from ideologies consistently seeking to undermine our collective existence?

There’s a historical arc of blatant resistance that exists in this community, whether it was Sikhs in the jungles of 1700s Punjab or these folks in the 1980s. We revel in the histories of the former and are shy to address the latter. It’s very understandable why. Hopefully, our work can spur more creative uses of writing to tell the tales of not only Sikhs, but other global groups and situations whose narratives have been discounted.

Would you like to tell us anything about the next project you are working on?

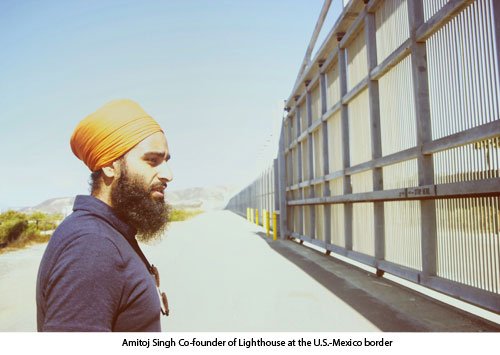

We’re working on a few things at Lighthouse right now. We’re following up our focus on Insurgency/Labh, with Borders || Frontiers. Here, we’re taking a look at how the construction and imagination of Borders shapes community. Each subsequent month, we’ll focus on new and different themes.

We’re working on a few things at Lighthouse right now. We’re following up our focus on Insurgency/Labh, with Borders || Frontiers. Here, we’re taking a look at how the construction and imagination of Borders shapes community. Each subsequent month, we’ll focus on new and different themes.

Also, in the fall, we’re looking to release more Sikh narrative pieces and we actually have an open call for submissions. This link is Lhouse.co/sikh. Our hope is to work with young Sikh writers to craft narrative pieces centered on a theme of resistance. Please do contact us if you’re interested in creating something!

What does Chardi Kala mean to you?

I think, personally, it’s a pursuit and a journey, which at some level can come to follow the mission of Guru Nanak. It’s tough for me at times, because I simply can’t reconcile the audaciousness of his vision with what much of our community is in pursuit of right now. If Sikhi is this revolutionary concept that we are so fond of saying it is, then a part of it must mean challenging the most rigid forms of oppression and power. In doing so, Sikhs would engage with the things that make everyone else uncomfortable. The neglected, the marginalized, the repressed, that which exists on the periphery of comfort. I feel Guru Nanak openly pursued these people and situations and they are the spaces we as a people should occupy.

So, what grand notions are we pursuing?

Is there anything else you would like to say?

There is a relationship with power we have which is unique. We are at our greatest when we reject the trappings of comfort. In this way, our offer with Labh is to establish confidence within our community that it’s not only alright, but expected, to create our own independent narratives. The descendants of some of the most fearless poets and scribes can’t be shy or scared to tell their own tales. Just do it, have some fun with it, and let the consequences be what they may.

Waheguru ji ka khalsa,

Waheguru ji ke fateh