Are you in pain?

This is the question Gurmeet Singh usually asks when he enters a hospital ward in the northern Indian city of Patna.

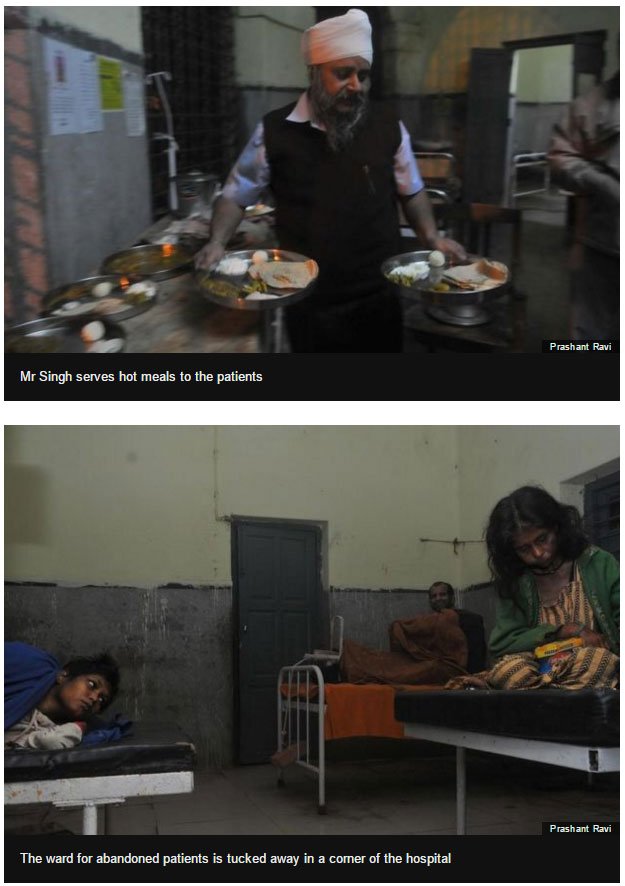

It is a damp and grubby facility with lime-green walls and stained tiled floors. Half a dozen gurneys for sick patients are scattered all over the ill-lit place. A fetid smell of urine and stale food fills the air. When night falls, rats slink out of a defunct fireplace and scurry for food.

The food - dinner comprises rice, lentil soup and some vegetable gruel - is insipid. A doctor and a nurse come on their rounds a couple of times a day. At other times, the patients appear to be left to their fate.

Appalling name

The place has the appalling moniker of the ward for lawaris or the abandoned. Put simply, it treats patients who have no family or have been rejected by them. When they recover, they are usually sent away to rehab homes - or returned to the streets.

For its inmates, the ward can be their home for months on end, for the streets, where they usually live and forage for food and shelter, can be a harsher place.

Tonight, it appears, nobody is hurting.

On a bed, lies a young woman who has had her limbs amputated after she was hit by a train. She's also pregnant.

The nurses call her Manju. Questions about her family, home and the father of the baby draw a blank. Some nights ago, they found her weeping on the cold floor after she was bitten by rats.

But when Mr Singh enters the ward, her face lights up, and she smiles wanly.

In the bed opposite her, a bedraggled woman with wild hair and wearing a dirty green jacket over a torn cotton gown trembles all the time. Tonight, she's holding a loaf of bread that the hospital gave in the morning. One night, other inmates say, she fell off the bed and lay on the floor for a while.

Across the room, Tapan Bhattacharya, 40, lies in a bed with his leg in traction. He says he landed up here with a broken femur after the auto-rickshaw he was travelling in overturned.

"Can you find me a job?" he asks. "I have nobody and nowhere to go to."

In another room, across the ward, two patients, Sudhir Rai and Farhan, appear to be lost in their own world, hoarding bread and fruit from breakfast and waiting for their next meal.

Farhan became an amputee a fortnight ago after he was hit by a train near Patna. Sudhir does not tell me what is wrong with him. There are no doctors or bed charts to check with. There's a stream of pale blood and urine flowing on the floor under his bed.

But, as soon as Mr Singh waddles into the ward, there's a frisson of excitement among its inmates. Their weary faces light up, some even manage to break into a smile.

By day, Mr Singh, a genial 60-year-old man, works at the family-owned clothes shop in a bustling city market.

By night, he is a veritable messiah to the residents of this foul kingdom of disease and disability, tucked away in a corner of a vast 90-year-old 1,760-bed state-run Patna Medical College and Hospital, one of the largest in the state of Bihar.

For more than 20 years now, Mr Singh has been visiting the abandoned patients' ward every night with food and medicines. He hasn't been on a vacation or stepped out of Patna for the past 13 years because, he says, he cannot abandon the abandoned.

The unfailing devotion to his patients is matched by Mr Singh's unchanging routine. Around nine every evening, he leaves his modest apartment - all his five brothers live on a floor in one of the city's oldest high-rises - and heads to the hospital.

He picks up some money to pay for medicines - the five brothers put away 10% of their monthly earnings in a donation box at home to pay for Mr Singh's patients - that are not provided by the hospital, where treatment is free.

On the way he stops at one of the many cheap hole-in-the-wall eateries that dot Patna to pick up bread, vegetables, salad, eggs and curd to feed to his patients.

'Dignity and care'

Once Mr Singh reaches the ward, he enquires about the patients' condition, playing, at once, nurse, doctor, provider and kin. He goes through their prescriptions and pays for the more expensive medicines, tests, scans, and chemotherapy for cancer patients. He also donates "a lot of" blood. Then he takes out the shining steel plates, and caringly serves the food.

Tonight the menu is piping hot bread, vegetables, curd and a sweet. The gruel that the hospital provides for dinner is usually left uneaten. In a bit, the patients are wolfing down their first proper meal of the day.

"All they need is some dignity and some care. The government is not even able to provide that. In the past 22 years that I have been coming here, nothing has improved in this ward. Nothing," says Mr Singh.

So doctors and nurses are scarce and treatment is scanty. The state of the hospital is a reflection of Bihar's dreadful public health services: hospitals have less than half the nurses they need; and only 2,289 of the sanctioned 4,851 jobs of doctors have been filled up.

On the other hand, bed occupancy rates regularly exceed 100%, forcing patients to be treated on the floor.

Mr Singh's involvement began some two decades ago when a woman selling plastic bags turned up at his shop carrying a badly scalded boy in her arms.

"It was a hot day. I saw tears in her eyes. Then I saw her boy who had got burnt. I took them to this hospital, and found that there was nobody to treat him. The doctors were on strike. The poor and the abandoned were the worst affected. I was very angry. I decided to do something about it."

Authorities want to fete him for his work and have sent him letters of admiration, but the Good Samaritan prefers to shun the spotlight. Tonight, he is busy feeding the dishevelled woman, who is having her first proper meal of the day. Then he'll tuck her under a blanket for the night.

"He is like God," comes a voice from the ward, as the diminutive Sikh man puts out the light and shuts the door to keep the cold out.

He will be back again tomorrow night.