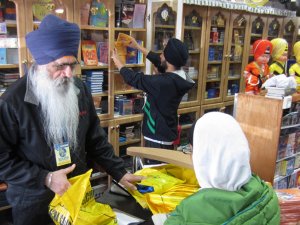

A short time ago, in a large gathering at the local gurduara both of us were commemorating, nay celebrating, the martyrdom day of Guru Arjan. Note that we label this a celebration, not a memorial service, as a death would normally be. Remember that the martyrdom of Guru Arjan was a revolutionary and transformational step in the progress of Sikhi; thus, celebration and remembrance are more appropriate.

Harjinder Singh Sabhraa, a young granthi, was on duty at the local gurduara and his ritual Katha really woke us up. His opening words noted the power of martyrdom – an idea that has uniquely defined the Sikh view of life amidst a predominantly Hindu perspective that barely seems to acknowledge the concept. Harjinder Singh was the first kathakaar to have made that point in our memory!

True that the idea of martyrdom comes to us from Judeo-Christian-Islamic theology. In the root faith – Judaism – martyrdom does not seem so well anchored or defined but it is. The Jews insist that if they hesitate to risk their lives for Torah, they risk their viability as a people. They seem to say, “we do not seek martyrdom but martyrdom has always sought us.” In the Jewish view, the ultimate purpose of life is life here on earth.

In the Jewish view of martyrdom, the Creator created the place where His very essence could be revealed, in all things, through every soul. But even God needs a partner in his work. He looks down upon His world and asks, "If I am to be there for you, are you there for me?"

As per the Jews. our answer should be that "Since Abraham, we have given our lives for You. In each generation, others have attempted to convert us, by the sword and by the kiss, and we walked through fire for no other reason than that we belong to You. We could have changed our faith, joined those more powerful and happier than ourselves. You gave us every excuse to walk away but we did not. In us You have a partner — an open door with us."

The two large religions, Christianity and Islam, that emerged out of Judaism, aggressively carried the concept of martyrdom forward. They developed a highly complex and elaborately developed legacy of martyrdom, most widely evident in the traditions of Crusades and Jihads. In the cause of their religions, Christians and Muslims waged horrendous battles, with each other and with others.

Christianity and Islam seem to promise endless rewards — the delights of heaven, including material comforts and, for men who die in such wars, an endless supply of virgins. We are left to wonder about similar rewards for women – hunks, perhaps?

The old English word “martir,” seems to have come to us via ecclesiastical Latin from the Greek martur, meaning ‘witness’ (in Christian usage ‘martyr’). In Indic languages, the equivalent word seems to have come to us from Arabic and Persian – Shaheed – or witness. Martyrdom is then rendered as Shaheedi. Shaheedi-purb is then the day of martyrdom.

At the outset, let’s explore very briefly the paucity of historical and sacred literature to explore martyrdom in Hinduism. Don’t forget that Hinduism is the oldest and overarching religious tradition in India. It has an all-embracing theology.

But is there a distinct and dominant idea of martyrdom, beyond its embryonic form, in Hindu thought and practice? We would have to say, probably not.

There have been some recent, seemingly laborious attempts at hunting and capturing ideas of sacrifice and martyrdom for a higher cause in Hindu history. Some old fables from Puranas are being reexplored and reinterpreted; for example, that to die fighting in battle guarantees a place in heaven (Shreemad Bhagvat Purana).

I would think that to die in battle alone does not justify honor; the proximate cause must be noble and beyond self-interest. Most wars have at their core the lure of salary, treasures, property and land. To transcend such morbid self-interest would have to be the first criterion for defining one as a witness to the Creator. And that is at the core of Sikh teaching. The history and language of Sikhi provide myriad examples of Shahidi (martyrdom). Let me cite a few – ranging from the almost contemporary into our hoary past.

Sikh history clearly speaks of fearlessness when facing mortal danger; it asks that we walk through life as if carrying our head on the palm of our hand (Sir dhar tali galee meri aao p. 1410) well before Guru Arjan. There should be absolutely no promise of heavenly delights like candy for a child – and there is none. For instance, when soldiers in the armed services of their country are recognized and decorated for courage in war, no soldier anywhere expects a bonus in his salary.

An unparalleled example comes from the lives of the two younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh. They were not quite seven and eight years old when captured by the Muslim Nawab of Sirhind. They were cajoled with offers of freedom, success and riches galore if they would only convert to Islam, and a horrendous death if they would not. They spurned the offers, were bricked up alive and now are revered as iconic martyrs in Sikh memory and historical narrative.

Why then to accept the life of a martyr? Simply stated, because it is the right thing to do. Dying for rewards, for land or riches is not martyrdom; it becomes a trade and a bargain. It is martyrdom only if one dies for a cause bigger than the self (Aap gavaaye seva karay taaN kitch paaye maan, Guru Granth p. 474).

But such matters are easier said than done. They have to be taught, but how? One can’t teach the attitude of the mind except by first demonstrating how it is done. Show and tell is the only effective way to teach. Guru Arjan showed how to resist temptations and die with dignity for a larger cause not his own in the 17th century, as did Guru Tegh Bahadur a hundred years later. Uncounted number of Sikhs followed in between and since. I repeat, the cause has to be bigger than the self.

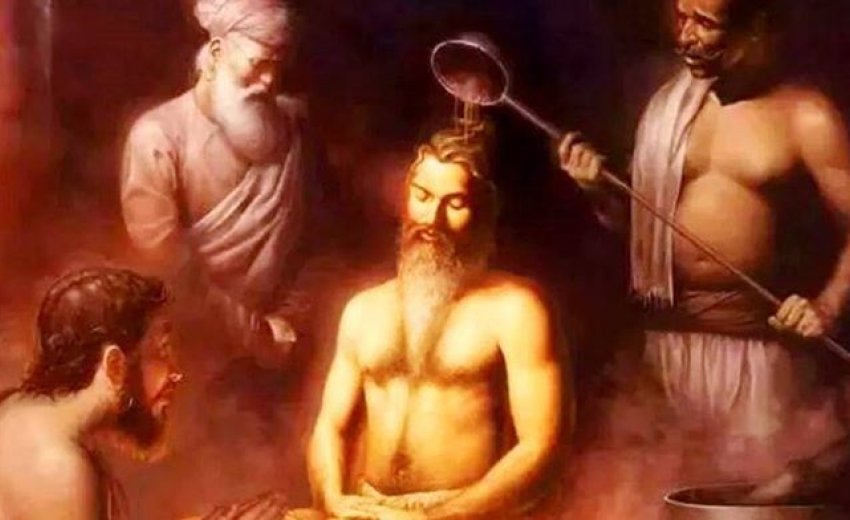

We also take brief note of some traditional practices that were prevalent in ancient Hindu India and the Hindu culture. Hindu traditions speak of balidaan or sacrifice, usually of animals at sacred rituals. This was not an uncommon religious practice; both ancient Greeks as well as Hindus have, at times, sacrificed their own sons as well. In fact, Lycaon, the King of Arcadia is said to have fed Zeus the roasted flesh of his own son. Many such examples exist in the Old and New Testaments.

Rajputs were the fighting arm of Hindu India then. If a looming battle held no hope of victory, the Rajput women helped dress the men for their last battle, bade them goodbye and then walked over to their own funeral pyre in a rite known as Johar. The idea behind this, tradition attests, was to prevent their sexual exploitation by the victors, but we suggest that such examples seem to hold the seeds of martyrdom, an idea that never flowered in Hinduism.

During India’s protracted struggle for independence from the British, a Sikh named Bhagat Singh and his two non-Sikh associates, Sukhdev and Rajguru, were sentenced to death by hanging. Bhagat Singh is now remembered all over India as a Shaheed (martyr), the other two have largely slipped our historical memory. We wonder why? All three deserved to be so honored. We think this is where cultural attitudes enter the equation.

Hindus, as mentioned earlier, have not entirely embraced the tradition of martyrs and martyrdom. Keep in mind that during that same struggle against British colonialism, 68% to 72% of all Indians sentenced by the British to death or life imprisonment were Sikhs. We remember them, but we dismiss from our memory that about 30% were non-Sikhs. They were most likely Hindus, as were Bhagat Singh’s comrades. Keep in mind also that Sikhs are a small minority in India, barely 2% of its burgeoning population, yet their sacrifice for the greater good has been massive.

Treasure and celebrate the lives of your martyrs and salute their memory.