Emboldened by its first mission to the Moon, India is to take on a target closer to Earth: Google.

Emboldened by its first mission to the Moon, India is to take on a target closer to Earth: Google.

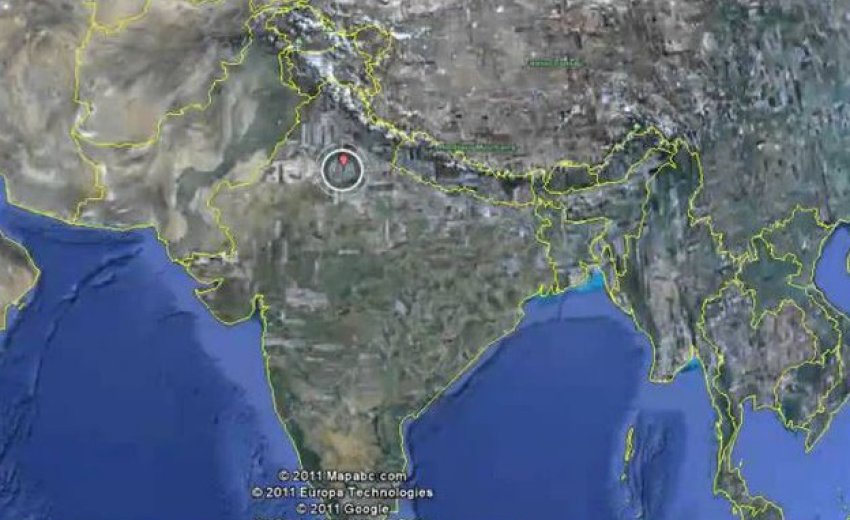

The Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro), which is based in Bangalore, the Silicon Valley of the sub-continent, will roll-out a rival to Google Earth, the hugely popular online satellite imagery service, by the end of the month.

The project, dubbed Bhuvan (Sanskrit for Earth), will allow users to zoom into areas as small as 10 metres wide, compared to the 200 metre wide zoom limit on Google Earth.

It comes as India redoubles its efforts to reap profits from its 45-year-old space programme, long criticised as a drain on a country where 700 million people live on $2 (£1) a day or less. It also follows in the slipstream of the country's first Moon probe, Chandrayaan-1, which reached the lunar surface successfully on Friday.

Bhuvan will use a network of satellites to create a high-resolution, bird's-eye view of India – and later, possibly, the rest of the world – that will be accessible at no cost online and will compete with Google Earth. If a pilot version passes muster, Bhuvan will be fully operational by the spring. There are also plans to incorporate a global positioning system (GPS) into the online tool.

The data gleaned by the state-sponsored project will be available to the Indian Civil Service to help with urban planning, traffic management and water and crop monitoring. G Madhavan Nair, the Isro chairman, said: "This will not be a mere browser, but the mechanism for providing satellite images and thematic maps for developmental planning."

There could also be commercial spin-offs. Experts say that Google Earth is being built as a platform for advertising that could be worth billions, and that Bhuvan will also address one of the issues taxing the web's biggest companies: how to engage users amid the mass of digital detritus that has accumulated on the internet.

Alex Burmaster, of Nielsen, the web analysts, said: "The amount of time that people spend online is reaching a plateau and websites are battling furiously for attention. Anything that relates to where a person is, saves a user time, and makes the web more relevant — especially geographically — is big news."

Isro officials say Bhuvan will provide images of far greater resolution than are currently available online — particularly of the sub-continent, a region where large areas remain virtually unmapped.

There are plans to charge fees for the most detailed information.

The agency intends to refresh its images every year — a feature that would give it an edge over its biggest rival and help keep track of the frenetic pace at which Indian cities are growing. A recent report by Gartner, the technology analysts, gave warning of the risk of relying on the "outdated information" used by Google Earth, which is now four years old and has been downloaded some 400 million times. About 2.5 million people used Google Earth in Britain last month, according to Neilsen, making it the web's seventh most popular application behind tools such as Apple's iTunes (fourth with 5.7 million users) and Windows Live Messenger (No1 with 14.8 million).

About 2.5 million people used Google Earth in Britain last month, according to Neilsen, making it the web's seventh most popular application behind tools such as Apple's iTunes (fourth with 5.7 million users) and Windows Live Messenger (No1 with 14.8 million).

Indian scientists will be mindful, however, that theirs is not the first country to take on the might of Google. In 2005, a French plan to create a Eurocentric search engine to defend against the "Anglo-American domination of the net", part of a €2 billion (£1.7 billion) raft of technological grand projets, fizzled without trace. Undeterred, a year later France unveiled Géoportail, its own answer to Google Earth.

At the time, Jacques Chirac, then the President of France, said: "We're engaged in a global competition for technological supremacy . . . It's time to go on the offensive." Bloggers quickly labelled the venture "another mind-numbingly stupid boondoggle".

-By Rhys Blakely in Bombay