My turban and beard have always made me a target of anxiety, stereotyping, or outright racism. Post-9/11, the hate has been taken to a whole new level. Sikhs have been killed, attacked, and verbally abused in a never-ending American saga. We might not ever know what was in the mind of 19-year-old Brandon Hole, who shot and killed eight people including four Sikhs at a FedEx warehouse in Indianapolis on April 16. But it hurts to keep seeing Americans who look like me paying the price for looking different, for standing out.

Ten years ago, in my anger and frustration, I accidentally found a way to confuse fellow Americans into thinking I am one of their own.

In the aftermath of the 2012 massacre on a Sikh house of worship by a White supremacist in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a photographer convinced me to don the uniform of an American superhero I had illustrated months before. And so, dressed as Captain America, I walked out onto the streets of New York City.

This is not a Black and White problem only. It is an American ailment. It is a human disease.

I found myself in a sort of twilight zone. I got hugs from strangers. Police officers took photos of me. I got access to a fire department truck. I got pulled into weddings. I was able to stand outside the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland while holding a banner that read: “Let’s kick some intolerant butt with compassion.”

Captain America does not exist, but the story does.

I got to experience the power of this fictional story. If Captain America was real, they could certainly sport a turban and beard to confront the villain that has been ravaging America for a long time. Narratives built around our perceived differences are villains that have to be confronted at all costs.

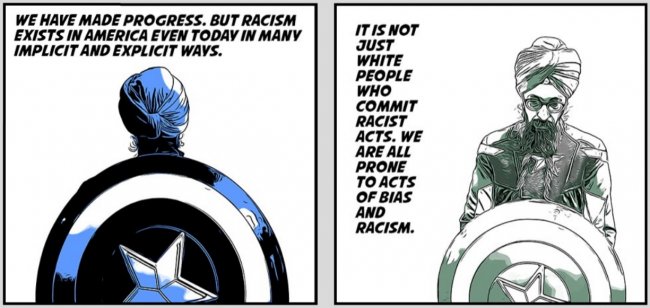

This is not a Black and White problem only. It is an American ailment. It is a human disease.

I am prone to this disease myself. I grew up nestled in two cultures, American and South Asian. An underlying message from both of these cultures has been that lighter skin is better than darker skin. Grand old tales have been crafted over centuries with this basic plot. Race in America. Caste in India. Millions have been enslaved, killed, and abused in the name of race and caste.

My cultural DNA is infected with this disease. One potential cure I have found is, first and foremost, to embrace my own vulnerability to racial bias. Second, I make it a daily meditation to unlearn all the biased narratives that have infected my body and mind. It is not an easy task at times.

While stories have been carriers of these infectious ideologies, stories can also be a force for slowly undoing the generational damage of racism. We are swimming in a sea of stories — in our conversations, in our books, and on our screens. . Who gets to create and tell these stories is of paramount importance. Stories have to be armed with truth. Stories have to represent our incredible diversity. Stories have to pierce through our contradictions, follies, and shortcomings.

It is easy to call those committing acts of bias “racists” in order to differentiate ourselves from that so-called tribe. It is hard to acknowledge what we share in common with those committing acts of bias and racism. We have the potential to do good deeds one day and commit a biased act at work or out on the streets another day. Me being a Sikh targeted by fellow Americans does not preclude me from my own bias toward others.

This is my daily meditation. To start my day with the realization that I must treat others how I would like to be treated. To end my day with a reflection on the rights and wrongs I have committed. To learn from my mistakes and be a better version of myself tomorrow. To always strive to do the right thing even if it means standing out alone from the comfort of a community.

I believe this meditation should become part of our broader culture. We have to be honest with each other and our children about our vulnerabilities. The story of America cannot be White-washed in our schools. Black Lives Matter is not a slogan. It is a painful wound from the story of race still being played out in America. It is not enough for institutions and companies to host diversity speakers once a month in their efforts to confront the story of race. White people are not the only ones committing acts of prejudice in America. Police officers, like every American, harbor bias. We have to create a space with our stories for these truths to be told.

Until we lay bare and learn from these truths, we will find ourselves tragic and repeated moments of loss fueled by perceived differences, us versus them dichotomies, and false jingoistic tropes.

The villain is around us, yes, but it can also manifest within us.