The middle-aged Sikh postman with the pink turban thumps on the door. The young woman sitting on the living room sofa wearily gets up.

“Is there a person by the name of Anuradha Bali here?” he asks, clutching a few white envelopes, not looking the woman in the eye.

This is a question that the 38-year-old woman might have often asked herself over the past two months. Until December 2, she was Anuradha Bali, Additional Solicitor-General of Haryana. Now she answers to the name of Fiza.

Between those two names, Anuradha and Fiza, lies a journey that has mesmerised India. It’s a saga of love, heartbreak, intrigue, feudal mores, betrayal, family drama and political suspense, one that propelled the woman from a relatively low-profile existence to being a national spectacle on primetime TV. It is set to play into Haryana’s sharp-edged politics. In a country where the personal lives of politicians are rarely the subject of scrutiny, her story could soon be a movie.

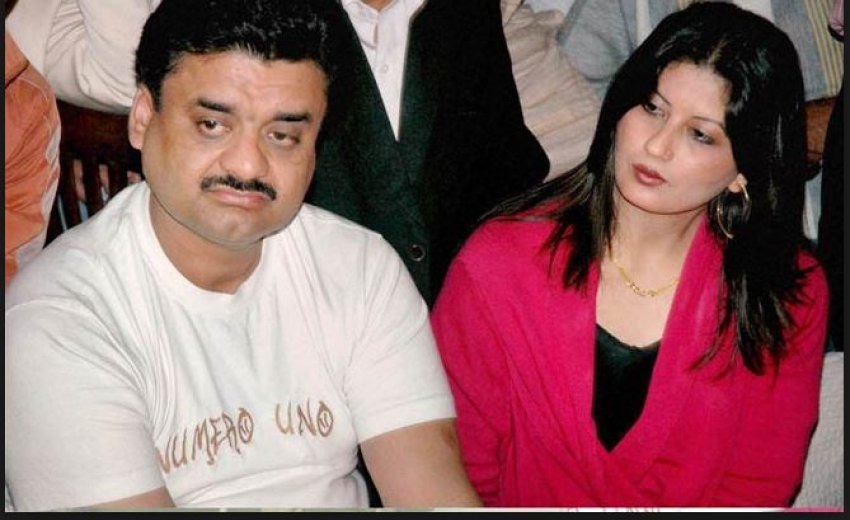

Anuradha became Fiza when Haryana Deputy Chief Minister Chander Mohan – son of political patriarch Bhajan Lal and a member of one of the country’s leading political families — gave up all he had, his job, his family and his religion, to be with her. On October 28 last year on Diwali night, Chander Mohan secretly drove out of his home and vanished. “He had done this once or twice before in anger. We thought that is what may have happened this time too,” says Deepak Walia, his close friend.

Anuradha became Fiza when Haryana Deputy Chief Minister Chander Mohan – son of political patriarch Bhajan Lal and a member of one of the country’s leading political families — gave up all he had, his job, his family and his religion, to be with her. On October 28 last year on Diwali night, Chander Mohan secretly drove out of his home and vanished. “He had done this once or twice before in anger. We thought that is what may have happened this time too,” says Deepak Walia, his close friend.

But Mohan — guarded then by commandos — did not reappear for more than a month. By December 2, he had converted to Islam and changed his name to Chand Mohammed, married the woman he loved, disowning his first wife, Seema, and his children. Chand and Fiza — who also changed her religion and name — lived together for weeks.

Then, equally suddenly, Chand Mohammed left his new home on January 28, and was found in New Delhi apparently drunk, professing love for his first wife. He seems to be inaccessible even to his friends and hasn’t returned to Fiza, who in the meantime, showcased everything from text messages to letters purportedly written by him in blood before the media in a bid to make him return to her.

This is not the last twist to a story that began in 2004 at a juice shop in a bustling Panchkula market.

Jab they met

“I was talking on the phone at a juice shop in Sector 32. That’s when he first saw me,” the nattily dressed Fiza says, her hands playing with her two identical mobile phones. Hair tied at the back, she’s wearing faded grey jeans, a black sweater, a grey kaftan, four rings (diamond-studded?), brown lipstick and silver nail paint.

Chander, who studied at the prestigious Lawrence School in Sanawar and loves cricket, table tennis and dogs, was an MLA, a rising star of Haryana politics. A man of few words, he is known to be religious but with a reputation of enjoying his drink and being a ladies’ man.

Married to Seema, daughter of a rich Rajasthani family, Chander has two sons and a daughter, the eldest son studying in Scotland, the younger son and daughter in Chandigarh. The younger son suffers from a debilitating genetic disorder. Seema, stoic and graceful, spent time with her ailing son, taking him to the movies, living a life away from the public gaze on her politician-husband. The couple lived in their 4,000-sq yard mansion with a table-tennis table under a shed, and the two other loves of his life: his two dogs, Bruter the pug, and Jojo the labrador.

In 2005, Mohan became Deputy CM, an apparent favour to his father Bhajan Lal who had been sulking at not being made CM and who later quit the Congress with his younger son Kuldeep to form his own party. And then Mohan, the man who could have had everything, lost his heart.

Anuradha, daughter of a retired army engineer, was also doing well in life. The eldest of four sisters, she began practising as a criminal lawyer in 1994. A decade later she was Assistant Solicitor-General. Along the way, she got married but got divorced within a year. She had dated other men since.

“Initially I kept away. I thought politicians are.... you know what. But he was very down to earth. Then he started to discuss his family problems, problems with his wife,” says Fiza. Over the next few years, they met secretly, had mushy phone conversations, and sent each other romantic text messages. “He had a colourful reputation, but I wanted to forget all that. The past is past, I told myself,” Fiza says.

“We could smell he was in love,” says Bipan Singla, one of his close friends. “We were not told, but we were not unaware.”

Then, Mohan started proposing marriage to her. Fiza says she made him wait for three years. According to her, he became desperate and began sending her smses like: “If you don’t marry me, I will shoot myself.”

Death came knocking in the Chander-Seema household in March 2008. His younger son died. The death shattered Chander. “We found him crying for the first time that day. He wept bitterly as he gave his shoulder to his son’s body,” says his friend Deepak Walia. The tragedy made him take deeper refuge in religion. He started worshipping and feeding monkeys every Tuesday, cows every Thursday, and worshipped Shani every Saturday at the Mansa Devi shrine.

Which is why what was to happen next surprised even the closest of his friends. He was about to give up the faith he had so passionately nurtured for years.

Married to the mob

On the morning of December 2, Rohit Mahajan, a former law school classmate of Anuradha, got a call from her. It was a bombshell: she was getting married, could he meet her in Meerut right away and be a witness? “Who is the lucky person?” Mahajan had chuckled. She didn’t say.

Mahajan, a civil lawyer, drove more than three hours to a small room in Meerut in Uttar Pradesh, where an Islamic cleric had laid a bedsheet on the floor and Chander Mohan and Bali sat face to face, the bride-to-be not behind a veil as customary. He wore a white kurta pyjama, she wore a salwar suit. Barely 10 people were present.

The qazi (priest) asked Fiza if she accepted the groom. She did. The wedding over, barfi distributed, they left in a hired car.

“They got married. They were happy after the marriage,” says Walia. “But there was a tinge of sadness too.” The all-powerful politician was suddenly an ordinary man. And he seemed to be taking it all well. They went to the market and bought clothes and things for their home. They watched Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi together.

This was an ordinary happy couple — taking walks in the park, going out to buy milk. Chand would hail passing carts of juice sellers to have sugarcane and orange juice. On January 13, the festival of Lohri, the two met every couple in the neighbourhood. At restaurants, managers refused to charge them. People asked for their autographs in public places. College students requested to have pictures taken with Fiza. Neighbours who earlier ridiculed Fiza started falling over each other to invite the couple home. Women gave up watching their daily TV soaps to sit on their balconies and watch the goings-on in their house.

“We barely ate at home, there were so many dinners to attend. We spent such a beautiful time together,” says Fiza. “People told me he looked nicer, he had also lost some weight.”

But the world was coming crashing down on this picture-perfect marriage.

Crash, boom, bang

The Bishnoi community, to which he belonged, declared Chand an outcaste. His family disowned him. His government sacked him.

Back at his mansion, his first wife Seema could not stop crying. “How could this happen? I wonder how he is?,” she asked visitors.

The newly-weds hopped between press conferences and TV stations, publicly declaring their love for each other.

But then, Chand left.

She reportedly tried to commit suicide. Then she said she hadn’t tried anything like that at all.

“May Allah give peace to my heart,” says Fiza, switching to Urdu. “Today I do not know who I am. If this can happen to a woman in an influential position, what about an ordinary girl?”

That notion resonates across Haryana, a state where ‘manliness’ is worn on men’s sleeves, where so many unborn girls are killed that it has the country’s worst gender ratio.

In interview after interview with Fiza’s critics, her character was questioned with one phrase repeatedly thrown as an explanation: “She is a divorcee.”

Two lives

Such is the fascination with the Chand-Fiza story that a Canadian filmmaker has offered Canadian $5 million to Fiza for her story to be made into a film. The offer, though, has yet to be made directly to Fiza.

Chander Mohan could have the law stacked up against him, with possible charges that include rape and cheating. As Chander — or Chand — deals with the legal dilemma, Anuradha — Fiza — also has tough choices to make; for starters, about her name.

“Anuradha Bali,” she signs on the paper held out by the postman.

Then she returns to the sofa. The phone rings shortly after, and after a second, she responds: “Yes, Fiza speaking…”