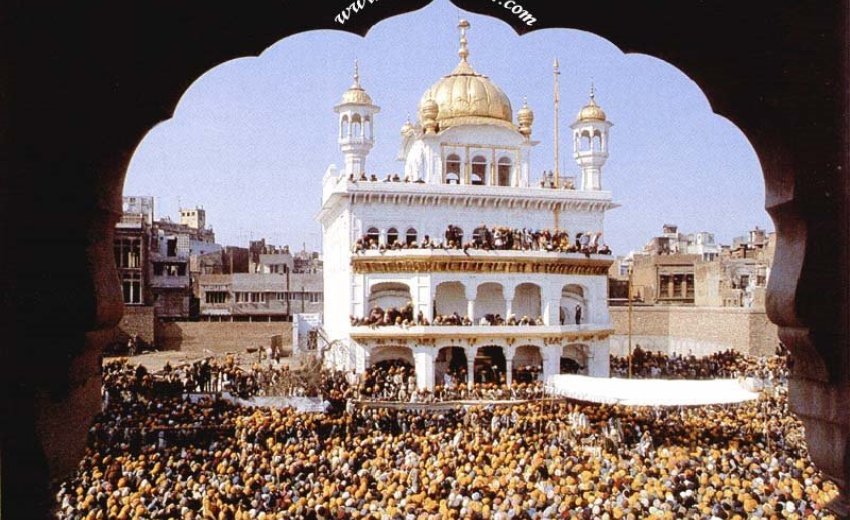

Over the last two decades, the Valley's Indian immigrants have built at least a dozen Sikh temples to serve a growing community.

Over the last two decades, the Valley's Indian immigrants have built at least a dozen Sikh temples to serve a growing community.

But many temples are often short of one thing: young adults, some of whom say they feel like outsiders.

They don't like the temple politics and don't have command of Punjabi, the primary language of the service.

They want more youth activities and projects to keep them interested.

"There's a generational divide," said 27-year-old Naindeep Singh, regional leader of the Jakara Movement, a nonprofit Sikh youth organization.

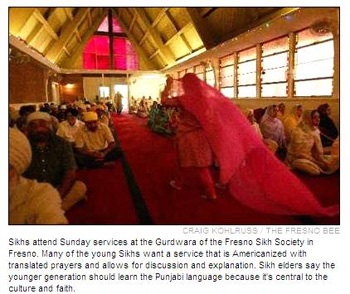

Singh, who is from Madera, said most of the parents are immigrants who observe the religion as they did in India, reciting memorized verses. Many of the youths want a more Americanized service that allows for discussion and explanation.

"It's evolving, but it hasn't evolved at a point where it's engaging the youth," Singh said.

Last month, the generational divide was the focus of the Jakara Movement's annual Sikh Youth Conference held at California State University, Fresno. Participants agreed to ask their temples to make more accommodations for young adults.

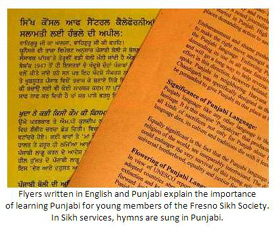

Some Sikh elders say younger Sikhs should master Punjabi because it's central to the culture and faith.

Some Sikh elders say younger Sikhs should master Punjabi because it's central to the culture and faith.

Still, those elders agree that changes are needed.

Ranjit Singh Rajpal, general secretary of the Sikh Council of Central California who emigrated from India to the United States in 1974, said most temples offer English translations of hymns and of the holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib, to address concerns of younger adults. Most temples also offer Punjabi language classes.

But Rajpal said youths who are in charge of providing English translations at some temples don't always stick with it. On some Sundays, there's no projector for the translations because the operator didn't show up, he said.

Rajpal, who is 58, also blamed parents for not pushing their children to learn Punjabi and go to the temple.

"The parents are not worried about that or are busy with other things -- working and trying to settle down," he said. "That's what's causing the feeling among the youth."

Parminder Singh, 38, of Kingsburg, agrees that parents must do more to teach their children Punjabi and the Sikh faith.

"Anytime you translate, you lose some meaning. We have to be bilingual," said Singh, whose wife is teaching Punjabi to their two children, ages 10 and 7.

Penny Mirigian-Emerzian, secretary of the Fresno chapter of the Armenian American Citizens League, said Armenian immigrants went through the same thing when their U.S.-born children were exposed to American culture.

"In the Armenian situation, the second generation of young Armenians did not know how to read and write in Armenian and resisted learning it," she said.

Mirigian-Emerzian, 86, said her parents forced her to go to an Armenian school, and she attended Valley Armenian churches, where the services were in Armenian.

"My parents retained the custom and spoke the language well, but I was born and raised here. As a young kid, I didn't want to learn Armenian, but as I grew up, I realized it was an advantage to learn another language," she said. "I wanted to be American. I thought why should I speak something else?"

Conflicts between immigrants and their children over religious traditions are not uncommon, said Rudy Busto, a professor of religious studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

"This is very typical of what happens in the second generation. The usual model ... is the immigrant church or religious institution is tied to the old country," Busto said. The younger generation is torn between their parents' traditions and their own Americanized values.

The younger generation "will adapt the tradition in ways that allow them to be both Sikhs and Americans," Busto said. The Valley is home to about 40,000 Sikhs. The principles of Sikhism, a religion founded more than 500 years ago in Punjab, India, and what is now Pakistan, includes belief in one God, truthful living and the equality of mankind.

The Valley is home to about 40,000 Sikhs. The principles of Sikhism, a religion founded more than 500 years ago in Punjab, India, and what is now Pakistan, includes belief in one God, truthful living and the equality of mankind.

At a typical temple, called a Gurdwara in Punjabi, men and women sit barefoot on the floor on opposite sides during the Sunday service. Hymns are sung in Punjabi followed by prayer.

Harjinder Dhillon, president of the executive committee of Singh Sabha Gurdwara in Fresno, acknowledged that some temples are resistant to change.

Harjinder Dhillon, president of the executive committee of Singh Sabha Gurdwara in Fresno, acknowledged that some temples are resistant to change.

"Some temples are so strict. There's no cultural dances and plays. They say it's bad to incorporate those things," he said.

Dhillon hopes the new temple Singh Sabha Gurdwara is building will appeal to younger adults.

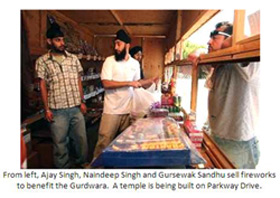

The temple on Parkway Drive between Ashlan and Shaw avenues will feature an educational institute, a gym, tennis courts, a playground and a prayer room.

The $10 million first phase is scheduled to be completed by next summer.

Dhillon foresees more Valley temples adapting to the next generation of Sikhs.

"If they don't adapt to the changing times, the temples will fade away with the older generation," Dhillon said. "We have to listen to their concerns."

- By Vanessa Coln / The Fresno Bee

The reporter can be reached at [email protected]