(RNS) — Despite belonging to the world’s fifth largest religion and despite being in the United States for more than a century, Sikhs are often left out of the national conversation in America. And when our stories are told, they are typically told through the lens of violence and victimhood: Look at these people who are attacked for how they look.

While it’s important to discuss the discrimination Sikhs face, it can be dehumanizing when that’s the only story ever heard. We are more than what happens to us; Sikhs do things too.

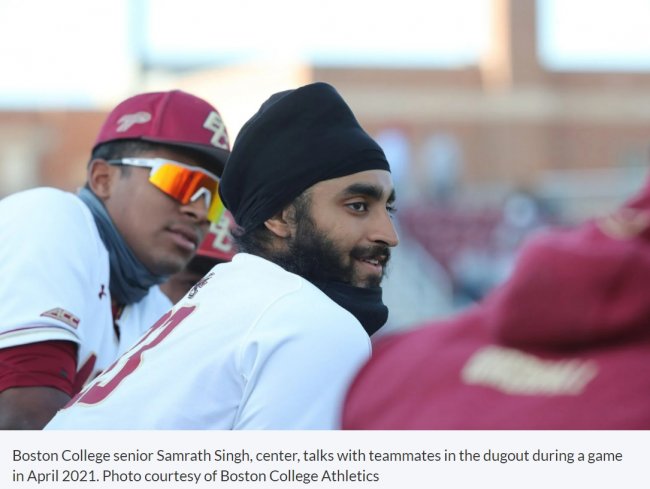

Take, for example, New Jersey native and Boston College senior Samrath Singh. The first turbaned Sikh to play NCAA college baseball, Singh has faced his share of discrimination, but he doesn’t want his story to be about that. He told me he focuses less on those negative moments and more on the values that help him navigate and transcend discrimination.

He also said a write-up that truly represented him would try to do the same.

I want to honor that outlook and share some of what he expressed to me on how his Sikh faith has guided him to success on the pitcher’s mound and in life off the baseball diamond.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me what it was like growing up as a Sikh in Princeton. Were there Sikhs in the schools you attended? Would you see other Sikhs playing baseball?

I attended the gurdwara in Lawrenceville called the Sikh Sabha of New Jersey. I loved being a part of the community there and some of my closest friends even now are from there. There weren’t a ton of Sikhs in my school, just a few. I was the only Sikh in my Little League who had a joora (topknot) and patka (small turban) and kesh (uncut hair).

I know this is a common challenge for a lot of Sikhs playing Little League, and one my brothers and I faced as well. How did you deal with the norms about wearing hats and helmets?

I definitely had to find little ways around baseball norms to be able to play. I was never going to wear a hat, and I didn’t feel comfortable wearing a viser over my joora either. So to put a helmet on, we had to think outside the box a bit. Any time I got a helmet, my dad and me would take out all the extra stuffing from the inside. Then I would tie my joora really loose, tie a patka on top — and then jam my head in there. It wasn’t ideal, but it got the job done and I was able to play.

Has that changed for you over the years? What do you do now in terms of baseball hats and helmets?

Well, I’m a pitcher now, so I don’t bat anymore and don’t have to wear a helmet. On the field, I just wear my turban and it’s not a big deal to anyone. Growing up, my parents and coaches would talk to the umpires in Little League about a religious exemption, and they always agreed. So that was easy.

Going into college, some umpires talked to my coach and noted I wasn’t conforming to the uniform policy. My coach responded and said you’re going to have to allow him to play as he wants, because if you don’t, you’ll be opening up a whole can of worms for yourselves. So my coach was able to resolve that really easily, and I could play and pitch while wearing my keski (wrapped turban). That was huge for me because my coach has been willing to fight for me and what I wanted, and he’s made my experience at the Division I level a lot better.

I imagine you’ve had your share of trials and tribulations traveling around the country to play baseball. What guides you in those moments when things get difficult?

I’ve had many where people have said all kinds of things to me and about me. But one thing I want to make clear is I don’t want to be seen as a victim. These are experiences that help shape who I am, but I don’t want people to pity me.

I’ve learned how to deal with these things through growing up as a Sikh in a place where there aren’t that many Sikhs, and through practicing a religion where we stand out wherever we go. To me, the whole reason we look different is so we stick out and can be a pillar of support for people in need. I’ve also learned there’s no need for me to be angry. If I respond in an angry or aggressive way, it’s not going to help anyone. If I can be at peace with who I am and my work is not dependent on these people’s words, then it’s like water off my back.

Are there any particular teachings from Sikhi that you lean on that you think might be helpful to other people who encounter difficult moments?

There are so many people who are bullied and discriminated against. That’s something I’ve had to face too. But it doesn’t do them much good to just focus on the negative. It’s more important for them to see and hear that these are trials and tribulations — that you’ll be stronger once you’ve gone through them. I believe there’s a reason for everything, that’s what Sikhi teaches us, and rather than feeling sorry for yourself, you have to remember that life is in your hands and you can take it where you want to. I’m confident in who I am and I love myself, and the people around me, my own beliefs, and my religion, have helped me accept myself and be proud of who I am.