This is an excerpt from a full article on Sikh resistance that I had the pleasure of contributing to with Sukhraj Singh. It will be out in March in Consented Magazine.

How free was the choice to enlist in the British colonial army? How authentic was the pledge of allegiance to fight for British freedom?

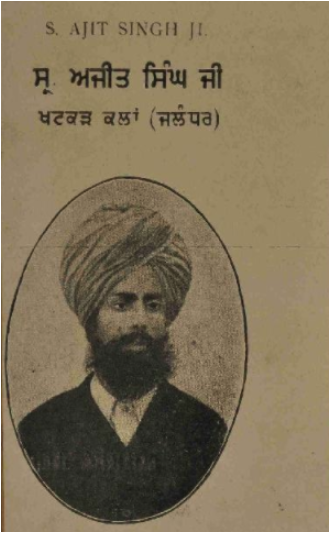

Who was Ajit Singh?

Who was Ajit Singh?

Sardar Ajit Singh’s autobiography recounts his experiences fomenting protest and ultimately attempting rebellion in the early 20th century around issues of economic justice and resistance to the imperial hierarchy of British rule.

What did Amrit or baptism mean to him?

He was a baptized Sikh who identified the key purpose/philosophy of baptism to be “...not to fear death, and to fight against the oppressors, tyrants and the unjust people and to protect the weak, the poor, the old, the children and womenfolk from all sorts of molestation.”

Radicalization is a good thing

His radicalization began early while witnessing the superiority that British agents were paid by Indian subjects. His revolutionary ideas deepen in University partly inspired by the biographies of the Italian revolutionaries Garibaldi and Mazzini.

His Mission

From 1903 to 1907, along with a host of fellow revolutionaries from across religious and regional boundaries, he led a protest movement that he sought to transform into an outright rebellion. This resistance movement was built by mobilizing peasantry and retired Sikh soldiers, formerly of the British military, to protest against economically punitive legislation up for vote by the British Parliament. The legislation would usurp local management of waterways and thus irrigation as well as imposing regressive taxation.

Building Support

To help rally support for the movement, he enlisted the support of the centrist Congress party’s Lala Lajpat Rai. Lalaji was sympathetic to Singh’s movement, though hesitant to openly agitate as it would be unharmonious with the more incrementalist Congress philosophy. Ultimately, Lalaji openly supported the movement and helped build a critical mass of protest among the peasantry and retired soldiers.

Political Agitation

Pamphlets were circulated and rallies were held espousing the exploitation of common Indians under the yoke of British rule. These ideas infiltrated the ranks of the standing military, and mutiny became a genuine fear of British administrators. In a particularly dramatic instance while Ajit Singh spoke at a rally “The military was called out and the commander of the military asked us to disperse failing which he would order shooting. Nobody moved from his place and he ordered for shooting, but Indian soldier instead of directing their guns at the public aimed them at their commander and said if he gave a similar order again they would shoot him. Seeing this he asked the Indian soldiers to return to the cantonment and himself also left with them.”

British fear of mutiny ran so high that ultimately, Ajit Singh and Lala Lajpat Rai were renditioned to the Mandalay prison in Burma where they languished for a year before their release.

Exile and Bittersweet Victory

Exile and Bittersweet Victory

After more agitation in India, Ajit Singh ultimately was forced into exile in the middle east and Europe where he interacted with many leading revolutionaries of the day including Leon Trotsky. His struggle for Indian independence continued from afar for 40 years until shortly before Indian Independence when he was allowed to return home. As independence unfolded, he lamented the intercommunal violence that began to unfold as India’s Partition set in. Though pleased to see British rule of India undone, he acknowledged that it was not the vision that he and his comrades had set out to realize.

Tune in to this week's episode of The One with Sukhraj Singh aka Sikh Talk on Youtube and the host of Sikh Archive on Instagram for a the first of a two part conversation on Sikh resistance movements over time and what they mean now.

Listen to episode 3 of The One here