Handing Over the Baton - The Next Gen Sikhs

Even though Sikhi is a relatively small religion, numbering only about 25 million in our overcrowded world, it is also a young religion tracing its origin from only about 550 years ago. Today Sikhi and Sikhs occupy center stage amongst human kind, many of whose origins are lost in antiquity. Yet Sikhi is mature enough to have impacted the world for several hundred years, since the time of its founder, Guru Nanak in the 15th century. And that Sikhs have influenced modern times, is a given.

I came to the United States when there were less than a handful of recognizable Sikhs in a mega-polis, the size of New York city. And then I spent years where there were even fewer. That gave new meaning to community, and its psychologically meaningful absence, being a minority, sometimes of one.

Now the home of the Sikhs is not just the Punjab but the entire globe. Our language, cuisine, culture and music are not tied to Punjab alone, or the lands that the Gurus trod upon, but to neglect the latter, would be to deprive ourselves of a supremely rich treasure. Tempus fugit. Time passes — but not without leaving its marks, its footprints, forever.

With this little essay I am focusing on the passage of the ages and on a new generation of Sikhs with a truly worldwide diaspora, from the Punjab to the whole wide world beyond. There is virtually nowhere in the world that there are no Sikhs. In North America, in the last century, they helped construct the Panama Canal and are now spread throughout this continent, engaged in every kind of profession. There are Sikhs in almost every country of Europe, including in southern Italy, where for example, they are engaged in producing gourmet classic cheese.

The catalytic event the partition of the Indian sub-continent in 1947 has changed us all, even the new generation that is stranger to the reality and trauma of fragmenting a nation but have grown up listening to the stories vividly narrated by their elders.

This essay is about where in the world Sikhs are thriving, within their own chosen professions, and otherwise. Sikhs, Punjabi or not, are not strangers to the world around them. Young Sikh men and women have been defining a place for themselves worldwide in academia and universities, and in varied professions, ranging from bankers, political leaders, neurosurgeons, businessmen, in the military, as taxi drivers and construction workers and so on, carving a niche for themselves even in the political life of the United States, Canada, Britain, Singapore Malaysia, Afghanistan and Pakistan. They define contemporary life in cities the world over. Sikhs have gotten their rightful place under the universal sun around the world as we know it. This is important to note even as humanity goes through difficult times, not only in the political sphere, but also economically. Sikhs will continue to define a prominent place in history of the 21st century as it unfolds.

The world has agonized on issues such as the empowerment of women which have confronted us possibly since the advent of humankind. I must add that the Sikh position on such issues has remained well ahead of the world and the times. (Unfortunately, I cannot be equally proud or pleased with our practice.)

I also look at the generation that founded and gave shape to a quarterly Sikh journal such as Nishaan, and that generation is now largely grey-bearded, or close to it. Then I see the new generation of Sikhs and their friends that is developing a loyalty to Sikhi, and they are much younger, with barely a hint of grey, if any. The difference comes to me not as an oddity but something to greatly celebrate. My generation’s day in the sun is almost done, and soon the baton must pass to a younger generation. The process is never easy; conflict is always close to the surface. The young don’t want to be held back; they see a welcoming road ahead. The old still want to bask in the glow of their experience and what they think was their tried and true judgement and leadership.

A last Hurrah! Yes, it is true that good judgment comes from experience, but the other side of the coin says that experience itself comes from poor judgment. Many of those of my generation come with truckloads of experience.

In an earlier essay entitled ‘Young and Wired: Up from the Grassroots,’ (published in the book Sikhs Today: Ideas and Opinions) my thoughts went to the founder Gurus of Sikhism. For over two centuries they nurtured a society from the grass roots. They didn’t go about cultivating the elite of the day — the many rulers, noblemen, satraps and the super-rich. Nation building requires a citizenry fired up by a common code of values, goals, expectation and behavior. And developing those fundamentals is exactly where the energies of the Gurus went.

The Gurus created a society defined by shared values and ethics, with transparency, accountability and self-governance at the centre. These are attributes that should remain supreme. That’s why the Gurus emphasised Sangat — an informed citizenry, in the collective. But as I said earlier, grass roots programs often get taken over by a top-heavy society in which the ordinary citizen (or the believer in religion) inevitably loses all sense of any of the things that are at the core of a just and progressive society or religion.

That is why I celebrate the young and wired of the Sikh world — young people who have created from the ground up new institutions to serve our growing needs: SikhNet, SALDEF, Sikh Coalition, United Sikhs, and The Sikh Research Institute — mostly outside the ambit of our dysfunctional gurdwaras.

In my lifetime of teaching in academia I have often said to postgraduate and doctoral students alike that, much like a new edition of a book, the new must be better than the old or else it is nothing more than a reprint. Similarly a student must, in time, excel the teacher, and a child must excel the parent, or else there is no progress. The world is populated enough already and needs no clones.

But a new generation must also guard the foundations of the past and use them, if possible, to support the new superstructure that they will build. If “the whole world is my oyster” as Shakespeare said, then no one is a stranger and no land is alien. And that is the lesson of the first words – an alphanumeric, Ik Oankaar – that opens the Guru Granth Sahib, the reservoir of all Sikh spiritual heritage.

I welcome the new and young voices, but I keep in mind that at birth, all of us inherit a world that has traveled eons along a time line of progress, and sometimes war and pestilence – often both good and evil byways of our own creation. The technology and markers of progress that we inherit come to us from where we are at a certain time on that timeline of existence and progress. This then is a debt that we must pay before our relatively brief but meaningful sojourn on the mothership we call Earth is over.

To whom are we indebted and in what form do we repay? Gurbani provides the way when it posits the stark question, “Eh sareera meriya iss jug mey aye ke kya tudh karam kamayya?” p. 917; in other words, what footprints will you leave in the sands of time?

The answer is simple and direct but never easy: Leaving the world even an iota better would be ample.

Note: This article was originally published as the Editorial in Nishaan Quarterly (New Delhi, India) Issue 3, 2017 and has been lightly edited for republication on SikhNet.

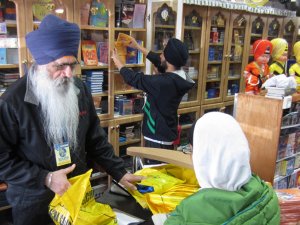

Photo by Guruka Singh Khalsa (Sikh Student Camp 2008 U.K.)