Keeping Alive the Stories of Partition through Oral History, Photographs, Keepsakes, and More

by Gayatri Manu

September 22, 2016: Artist and oral historian Aanchal Malhotra talks about how she is collecting stories of everyday objects brought over by families at the time of the Partition.

![]() anchal Malhotra is a writer, oral-historian, artist, and most importantly, a storyteller. Her seminal work, called The Remnants of a Separation, is by far one of the most intriguing alternative histories of the Partition.

anchal Malhotra is a writer, oral-historian, artist, and most importantly, a storyteller. Her seminal work, called The Remnants of a Separation, is by far one of the most intriguing alternative histories of the Partition.

It is a curious inspection of the objects that refugees took from their homes when they left in a haste to cross the border in 1947.

|

|

I always used to think that asking the right questions would generate the right kind of answers. In fact, a professor in Montreal would frustratingly joke with me about why I always asked the right kind of questions. But that’s the thing, even questioning takes commitment, perhaps in the same amount as answering does. When I structure an interview, it generally allows for conversation to build the questions. But that requires one to probe, delicately yet assertively, towards a greater memory or truth. Like an archeologist, dig deeper, wonder more and excavate further towards the very heart of things. But I think at times, I might take being a researcher for granted because though it takes a lot out of me, I am still the one questioning. Not the one answering the questions. There is always room for distance, objectivity, detachment. But this week, I was faced with three instances of having to answer questions and be in the foreground rather than behind a camera or a notebook. @vajor tuned the tables on me, turned the camera on all my awkward glory, drawing me out of my comfort zone and into the world I write about. We walked through the alleys of the old city, talked about Delhi, lost practices, and most importantly, memory. From nani’ s minkari bangle I always wear, to the knife that my dadi carried in her pocket when she fled from D.I Khan, the simple things that bring us joy to the beauty of our Capital, @vajor compiled my rambles and anecdotes into a beautiful video that makes the life of a researcher look far more glamorous than it might actually be! #remnantsofaseparation #vajor #delhi #india #museofthemoth #memory #history |

The 26-year-old was prompted to begin this project in 2013 when she was visiting her grandfather along with a journalist and friend, Mayank Austen Soofi. Her grandfather lives in Delhi in Roop Nagar, which was once a refugee colony. While Mayank was asking questions about old houses in Delhi, her grandfather’s older brother pulled out a gaz and ghara, which the family had carried across the border in 1947. The gaz is a yardstick that was used for measuring fabric in his father’s clothing store in Pakistan and the ghara is a vessel that his mother used for serving buttermilk.

While the objects made Aanchal immensely curious, what fascinated her even more was the glazed look on her granduncle’s face as he talked about the past. According to her, “When we were sitting there and talking about these ancient objects, something very strange happened. While discussing the past, he seemed to go to another place, it was a very transportive experience and I didn’t realise that objects could do that to you or hold those kinds of memories.”

|

|

In the last four years, the primary question everyone asks me about the oddity of my research subject has transformed from a ‘Why’ to a ‘How’. Why the need to archive objects has become How do you archive objects? Where do you find them and how does the conversation about them even begin. I would have liked to say that I follow a structured model in both approaching people and beginning conversation, but really the work has grown larger organically, sporadically and unexpectedly. Because there is not much written about material memory and migration in the context of the subcontinent, the nature of my questioning about these objects begins from sheer curiosity. Questions grow out of answers and I almost never have a ready questionnaire. I often sit with people for hours, sipping cups of chai and juice, talking about the past and present. Our conversations always begin from the mundane and never from migration, but eventually, we reach some sort of common plateau- after hours of talking about their daily routine, families, children, grandchildren, tambola nights, knitting, weaving, traditions- the question can finally begin to be grazed. We need that time, those banalities, that frivolous delving into the mundane, a comfort level before the words Partition, batwara, taksim or Pakistan can be mentioned. Here is me, seemingly serious, listening to the story of a migration by sea, from Karachi to Bombay. #remnantsofaseparation #india #pakistan #delhi #bombay #karachi |

Aanchal has been meeting people from the Partition era and speaking with about the objects they brought with them, ever since she was 23 years old. How does she find her subjects? Aanchal’s response is:

![]()

“How does a 23-year-old know people who are 85 years old? They don’t. Amazingly, news of my project just spread through word of mouth. My aunt would go for a walk in Defence Colony and she would approach people who look like they had migrated from Pakistan. But it’s important to note that I wasn’t just looking for refugees but for the belongings they carried along with them. I wanted to go into their houses, ask them about their clothes, books and jewelry, which is a pretty weird request from a stranger. It is a very intimate and sad thing to be discussing, so you need some level of comfort with the person. But if you spot a ring on someone’s hand, you could begin with, ‘Oh this ring looks interesting. How did you get it across the border? Is it from your mother? Where did she come from? Who gave her this ring? Did you ever want to sell it?’”

|

|

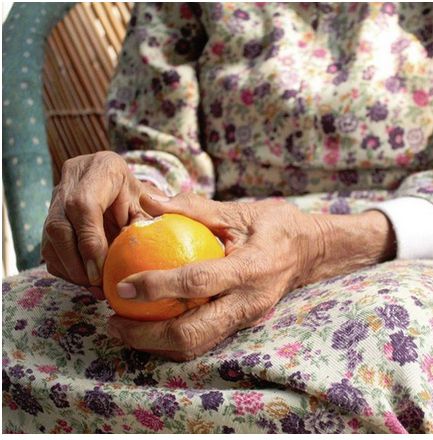

She reached for the orange lying on the table and carefully, began peeling it. ‘I just keep thinking’, she said, ‘how different our lives would have been if we continued to live in Lahore.’ I nodded, my eyes fixed on the orange peel. Her fingers moved deftly around the fruit. ‘It’s amazing how one thing can change the course of millions of lives. And it happened, just like that. It was like a mad unraveling, quick; spontaneous and uncontrollable.’ She stopped peeling. The orange was naked, the peel a perfect spiral. An unravelling. Then, as if to convince herself rather than me, as if this were the one piece of truth that lived within her, she said sadly, ‘I promise you, beta, no one expected it, no one imagined it.’ In response, three quiet words escaped my lips- I believe you. And as if to magnify the vivisection, slowly and ritualistically, she split the orange down the centre, one half of the fruit for her and one for me. My gaze followed the stray lines of juice that trickled down the side of her fingers, almost reminiscent of the tributaries of blood that flowed in 1947. #remnantsofaseparation #india #delhi #lahore #pakistan #history |

Aanchal’s grandparents, on both the maternal and paternal side, are from Pakistan. When told them about this project, they responded with various levels of enthusiasm. She says, “Despite belonging to a family of refugees, I realized that I haven’t thought about the Partition or studied it. They teach us about the Partition in school but that’s a very shallow understanding of the events. And most of us don’t talk about the Partition because it’s not really dinner table conversation, right? So, naturally, we don’t question what we don’t know. I realised that the journey or migration must have been very difficult because people often left at a moment’s notice and they weren’t able to take things that were important to them. I started by talking to my family – after coercing my grandmother to talk about it for 4-5 months and repeatedly begging, ‘I don’t know my own history, you have to tell me!’ she finally gave in.

She said, ‘Ask me before I forget.’"

|

|

There she was, dressed in a brilliant jade salwar-kameez and a cream cardigan. Her silver hair was styled into a bun, fastened with white clips. In her ears, sat jade earrings and on her fingers were stacked multiple rings. Her elder daughter, also a writer, accompanied her. She draped the jade dupatta around her mother’s shoulders as they sat down and then helped her adjust the small hearing aid into her ear. The poetess crossed one hand over the other, her gaze still fixed on me. Small wisps of silver escaped her bun and crawled down her neck. I inched forward to greet her. Before I could say anything, though, she spoke, depositing between us a fact, which has since propelled my belief that the accumulation of time and stories, is perhaps mutually exclusive in life. I am 90 years old. #remnantsofaseparation #india #delhi #pakistan #langarial #lahore #books #poetry |

It is apparent by the age of the subjects she interviews that the essence of her oral history project is to record these experiences before they die.

When asked whether she thinks the Partition is central to the modern Indian identity, considering that more than fifteen million people were uprooted, she says, “You learn history in school, yes. But do you retain any of it? No, because of the prejudiced way it is taught. History is supposed to be a story and not a series of events. It is stories of people that will get people more interested in history. Instead of listening to a lecture about the Partition, what is more interesting to me is the story about a woman who crossed from one country to another and the challenges that she faced.”

|

|

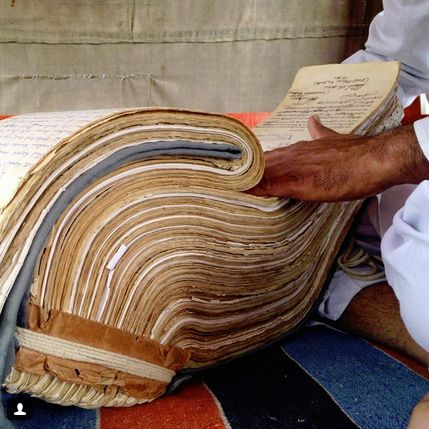

In one of the recordings I did with my dada, he had asked me why I wanted to know about his life before and journey to India in 1947. What would it change, he asked. What would I do with the story, the past was still the past. And I remember looking at him straight and telling him that I was a product of everything that came before me. I existed because of the events that happened in the lives of my ancestors and so I needed to know, for my own knowledge, I needed to know the past. When we went to immerse his ashes in the Ganga this February, we visited the priest who looked after all the Malhotras from Qadirabad, Pakistan. I have been wanting to share this image for very long and now seems like the right time. This is everything and everyone who came before me. This is our family tree, it's called a Pothi. Recognizing the red flag atop his hut on the banks of the Ganga, we had made our way to see him. Your family tree has been passed down to me from my ancestors, he said to us. Then, from the corner of the hut, he extracted a large oval shaped bundle covered in dark grey cloth, whose inside resembled the opened bark of a tree. Lines of varying yellows and browns decorated the surface in the form of aged paper. He unravelled the chord and sheet by sheet, flipped through to find our family. We all sat huddled together, cold after the requisite dip in the holy water, and watched him search for our particular genealogy. Slowly, he read out as far back as five generations, and as all of us nodded, he told us that 150 years of our family history lay in this book. Then, when he located the exact page that spoke of my dada's brother’s demise, he picked up his pen and as if reuniting the brothers in death, penned down my dada's details next to him. I had never felt like I belonged to some place or some thing or some people as strongly as I did in that moment. I was there because of everything and everyone who had come before, and there they were, staring up at me from soft, mustard coloured pages. #India #Pakistan #delhi #Punjab #death #love #familyhistory |

Through the oral history project, Aanchal is keen on bridging the divide between the narrative that reflects human experiences and the narrative that supports certain academic/ political theories. She is aware of the fact that human experiences should go in tandem with serious academic discussions. This approach to archiving history is apparent through her Instagram feed, which is subscribed to by almost 10,000 people worldwide.

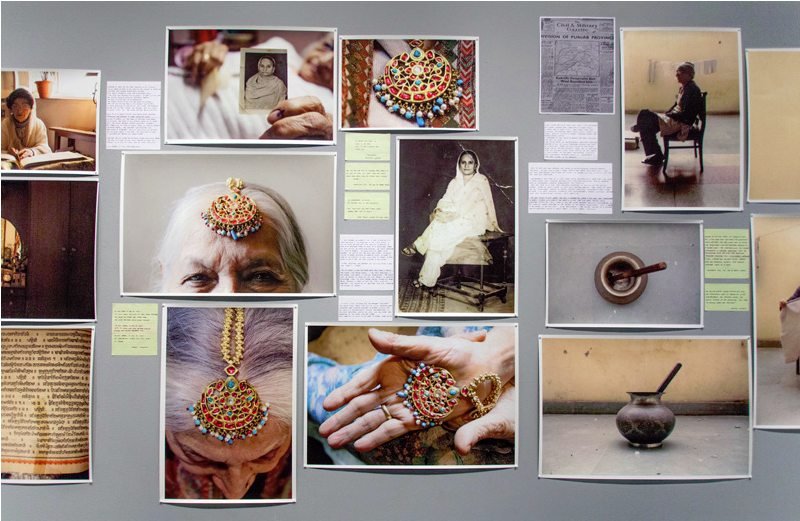

The feed features images of old books, toys, jewellery, and even utensils, along with captions that evoke a flood of nostalgia.

|

|

Delhi is not only a city of cities, but also one of villages, officially numbering up to 369. In Jonapur, a village in the Chattarpur area, there still exists a settlement of old havelis that were constructed before the Partition. Today I was invited to one such haveli, restored from the inside, yet still retaining all its old world charm and elegance. The area around the haveli was as if stuck in a time warp, as old as the legends that roamed its streets. The men sat in clusters smoking hookahs and playing taash, the women congregated at the thresholds, heads covered with their dupattas. As I stood in the incredible courtyard of the haveli, its owner told me a story that the women of the village that narrated to her. ‘A few years ago’, she said, ‘a taxi appeared outside the house next door and all the villagers gathered around it. Back then, the house wasn’t as pakka, the walls were still old, the construction was from pre-1947 and it resembled its original form. From within the car, a man emerged, creating ripples of conversation among the crowds. Where are you from, they had asked him, what do you want? He looked around at the crowd and said, I am from Pakistan, this was my makaan. I had left something here in 1947 and I have come to take it back.' The narrator paused and I held onto even that silence. I had only heard of such stories, but standing in Jonapur now, in the middle of a haveli from history, this incident seemed a graspable legacy of the Great exodus. My eyes followed her and she continued narrating with both her words and her eyes, 'The inhabitants of the house were old, they led him in and watched in wonderment, as he knocked open a wall and extracted from it belongings that he had embedded nearly seven decades ago!' #remnantsofaseparation #delhi #india #villages #history #memory |

Aanchal says, “Oral history is a very important and underrated source of telling the history of the Partition. The more I learn about where I came from, the simpler it is to understand why I am the way I am. Keeping alive the memory of the Partition is important. We shouldn’t suppress the gory aspects of the Partition and we shouldn’t forget the glory that existed before it.”

Check out her blog and Instagram to know more about Remnants of a Separation.

------------------------ |

|

Complete installation of 'Remnants of a Separation' at FoFA Gallery, Montréal, 2015. |