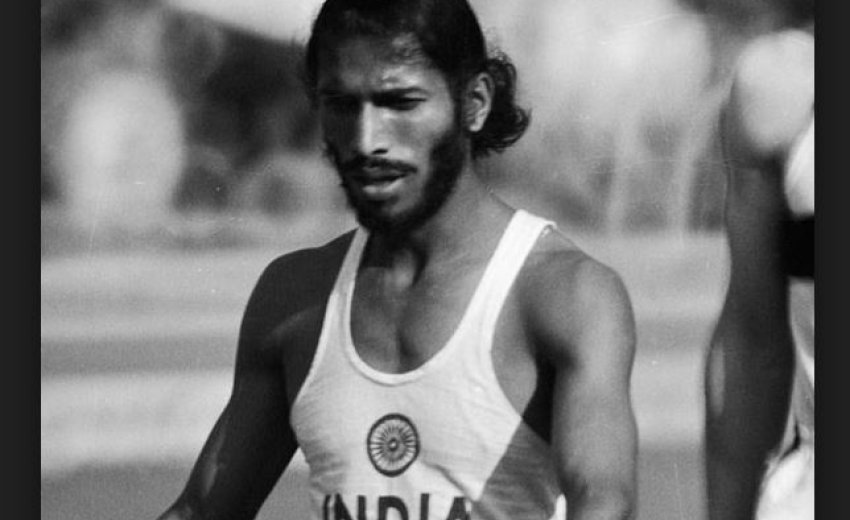

Now in his 70s, voice still strong, Milkha Singh knows it's Olympic year, he knows journalists (like me) will call and ask him about that day 48 years ago and dredge up a memory so piercingly painful. He has won four Asian Games gold medals, and one Commonwealth Games gold, yet it is not his many victories but one failure that people ask about. He sighs. He speaks.

Now in his 70s, voice still strong, Milkha Singh knows it's Olympic year, he knows journalists (like me) will call and ask him about that day 48 years ago and dredge up a memory so piercingly painful. He has won four Asian Games gold medals, and one Commonwealth Games gold, yet it is not his many victories but one failure that people ask about. He sighs. He speaks.

India has won a fistful of individual Olympic medals, bronzes by KD Jadhav (wrestling, 1952), Leander Paes (tennis, 1996), Karnam Malleswari (weightlifting, 2000) and a silver from Rajyavendra Singh Rathore (shooting, 2004). Yet Milkha Singh's story of a bronze missed in Rome 1960, is the most irresistible, the one we return to constantly.

Perhaps because heartbreak, as a story, is often more powerful, and poignant, than triumph. Perhaps because in 2008 India expects medals, but then in 1960, in a country that had savoured independence for just 13 years, where facilities were few, contending for medals was a more romantic pursuit.

Different world

India's progress in sport has not yet manifested itself in medals, but its strides are quiet and surer. Last year swimmer Virdhawal Khade's parents, from Kolhapur in Maharashtra state, agreed to the once unthinkable: letting him delay his class 10 examinations to qualify for Beijing. He did.

One of these days, hopefully, India will give back to him by producing a runner who wins an Olympic medal

Technology is no longer foreign to Indian athletes. Khade has been privileged to use Speedo's breakthrough LZR Racer suit. World champion shooter Abhinav Bindra has been hooking himself up to a machine that identifies what activity is going on in his brain when he is shooting well. As he told me: "The key is how to train that area of the mind so it is routine to get into that state."

Milkha Singh's world bore no resemblance to this. With a straightforwardness that is immediately disarming, he says that when he joined the army, "I came from a remote village, I didn't know what running was, or the Olympics".

Context gives Milkha Singh's story its searing beauty, the environment in which he ran gives his tale uniqueness. PT Usha would lose Olympic bronze in 1984 by an even crueller margin, yet in a comparison of tragedies he wins because of where he came from, what he endured. Usha did not work less hard, but it's impossible to compete with a man whose parents were killed, some reports say in front of him, in the carnage of India's partition. Whose temporary home for a month was a platform on Delhi's railway station.

His beginnings as an athlete can be linked, he says, to a five-mile cross-country run that every jawan (soldier) had to run. The top 10 were to be given further training, and so he ran it, was stricken by a stomach pain after just half a mile, sat down, but then got up, telling himself, "I have to come in the top 10". He came sixth, he says. The legend had started.

He was told then to run 400 metres, whereupon he asked, "how long is that?"

"Ek round," they said. One round, he thought, could not be such a big deal.

He was not familiar with spikes. Nor a tracksuit. But what he had couldn't be manufactured in a factory. " Aag thah andar, " he says in Hindi ("I had a fire inside").

Discipline, hard work, will power: he says the words with the devotion of a man nursing prayer beads. His own perseverance takes many forms, in the blood he reportedly urinated because he worked so hard, in the oxygen that was supposedly used to revive him after practice. In an interview in 1996, he told me: "My experience made me so hard that I wasn't even scared of death." But one story reflects his desire clearest.

Almost hero

In 1956, he journeyed to the Melbourne Olympics, just a novice who exited early in the heats. The 400-metre gold medallist that year was Charles Jenkins, and Milkha, taking with him an interpreter who spoke "tuta-phuta" (broken) English, met the American and asked for his training schedule.

Come back after a few days, Jenkins told him. "So we went," says Milkha Singh, "and he gave me his coaching schedule, for hill running, for sprints, for starts, for weights."

"And I decided unless I beat his record (46.7, hand-timed) I won't stop."

Two years after Melbourne, he did beat that time, in Cuttack, his run eliciting such disbelief that the track was measured again.

Four years after Melbourne, he was a medal contender at the Rome Olympics. He'd run and won so often around the world that he says he had 20 passports. He was ready, an athlete poised for his moment.

And this is when the story must be hard for him to tell, for however many times he tells it, the result never alters. He is always fourth. He is always .1 of a second too late. He is always the almost hero.

What happened in the 400 final? Was it the fact the final was held, for the first time since 1912, on a different day from the semis, and Milkha Singh says "that killed me, I was alone thinking about the race, no one was allowed to meet me".

Was it, as he always says, that he went out too quick when the gun went off? "It went in my mind that I was running too fast and I may not finish." So he slowed, broke his rhythm, couldn't regain it. Goddamn it.

"It was bad luck", says this proud man, "for India and Milkha Singh." And it was, for both nation and man in 1960 were trying to make themselves heard, be noticed, and perhaps this is why he still sits in the memory. In a land not given to nicknames, this Flying Sikh almost everyone Indian knows.

Milkha gave India medals in Asia, determination, pride, an unforgettable story and a terrific son called Jeev. One of these days, hopefully, India will give back to him by producing a runner who wins an Olympic medal. I think he'll like that.