Overview

I have written a three part essay on the themes of identity crisis and Sikh activism, and their interrelation to the path taught by the Sikh Gurus. The purpose of writing these three parts is to provide a critical analysis of Sikh individual and organizational behavior in response to bigotry in the United States. Part One serves as an introduction, starting with my personal experience of where everything began in the US: the events of 9/11 and the aftermath. Part Two explores Sikh activism and its response to the acts of bigotry post 9/11. Part Three, then, looks at how a Guru-centered perspective would develop a response to the same issues.

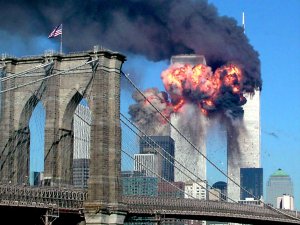

Part 1: 9/11 — Where it All Started

Like most Americans, I remember exactly where I was on 9/11, but I also remember who I was.

When news broke out about the twin towers being attacked, I was sitting in my high school Spanish class. Word had started to spread around the school of something big happening. The teacher had not yet entered the room and there were five minutes before class would begin. One of the students realized there was a television in the room and decided to see if the TV would get reception.

It was afternoon, but we could not tell because our classroom was a trailer hitched to the outside of the school premises. The only functional blinds were jammed shut, and the lights in the trailer were barely sufficient. We sat in a gloomy box, preparing to watch what another box had to say.

Speculation about whether these attacks had been planned and who would have planned them had already begun to fill the news coverage. We all saw footage of the two planes pummeling into the twin towers, the smoke from the buildings billowing out on the TV screen, with the video camera zooming in and out. We felt as if we were there and could touch the smoke, the building, the concrete.

Everyone was full of sympathy and shock. Some worried about those stuck in the towers, trying to make their way out. Others could not believe that someone would do such a thing. A few even wished they could be there on the streets personally helping however they could. I engaged in discussion with classmates around my seat. For one spectacular moment, it felt like we were all one, American, in a shared tragedy that would forever bind us together through the chaos and struggles to soon follow.

I grew up in India for the first nine years of my life, and at the time of 9/11 had only been in the US for six years. This is why, at the time, I neither realized the full significance of the attack on the twin towers, nor was I as shocked by it as my peers. You see, I had grown up watching movies from an industry that had stars with infamous reputations of terrorist connections and activity (i.e. Sanjay Dutt), and in a country where news of “atankwadi” (terrorist) activity was a daily norm. I even remember my childhood best friend’s family being routinely harassed by Punjab police because they accused my friend’s father of being an “atankwadi.” I remember my friend’s father disappearing and the subsequent darkness that clouded my friend’s home. So for me, human tragedy was not as shocking; it was a norm of being human and existing in a chaotic world.

Hence, when the moment occurred that would greatly shape the next 12 years of my life, I was not prepared. I was turned around in my seat, not facing the rest of the classroom, discussing with my friend about how such activities are a normal part of the rest of the world, and that whoever was dumb enough to attack the United States was going to have their world turned upside down and destroyed. As I continued talking to him, he told me to shut up and turn around to look at the TV. The news station had put up an image of Osama Bin Laden: one of the persons suspected for planning these attacks. And then, it happened. The moment.

After the image faded from the screen, it seemed as if a hive mind was in control. In unison the entire classroom was staring at my friend and me. Suddenly, I became aware that in this ocean of white, my friend and I were the only specs of color. We looked almost nothing like the man on the screen, except for the brownness of our skin. We had no beards and no turbans. And yet, the staring continued for an awkward while longer. As if this white mass had something it wanted to say, something it wanted to do.

Never had a room full of white looked so dark. I looked at my classmates and asked why they were staring. Not being able to provide an answer, slowly each one shook from his or her stupor. My classmates began looking around at one another and started talking again. Except for a few. I did not notice them.

My friend did.

He tapped my shoulder, so I turned around to speak with him. He nervously chuckled and said that I was really brave to confront the class, but did I not realize that the teacher had still not entered the room? That the class could have at the least beat us to a pulp or at worst murdered us? I told him to stop being ridiculous, that he was still just in shock from the news, and we had nothing to do with whoever was on the screen. I told him that we did not even look like the person, nor share the same religion (often the identifier to get the blame for individual acts). My friend was a Hindu and I a Sikh.

That was when he pointed out the classmates who were still staring at us and now discussing something. From his angle, he informed me that it looked like they were toying with a blade while clearly talking about us. My friend became afraid for his life, while being shocked at why I was not. He thought he was going to die, and after some discussion, I finally got him to calm down so that we could rationally discuss what to do.

Soon after, the teacher entered the room. I remember learning nothing of Spanish that day. The entire class time we saw those few kids continually staring at us and planning something, while my friend and I discussed how we were going to respond and find a way to walk back safely into our school from this trailer. It never crossed our minds to talk to the teacher. We were gripped in the moment of us vs them. She was pale as white could be. And in that moment, after experiencing the surrealism of the sudden color contrast in the room, white could not be trusted.

I do not remember how we got back to the school main building. I just remember that whatever those kids planned, they did not execute, that the momentary danger had passed. But a fear had gripped my friend that made him paranoid for several months, the same fear and paranoia that would grip non-white and non-Christian communities across the nation, and motivate their actions for over a decade.

That day a lesson and realization dawned on me. Just a moment earlier, we had all been Americans, suffering and experiencing together. But with just the flick of an image on TV, the only Americans became white Christians, and the rest of us were obnoxious guests who had overstayed their welcome. It did not matter whether you had a beard or not. It did not matter whether you wore a turban or not. It did not matter whether you were a Sikh, Hindu, or Muslim. It did not matter whether like me, you were proud to be American and considered Patrick Henry’s statement of “give me liberty or give me death” a life motto. All that mattered was that they were White and you were not. They were Christian and you were not. And that made you an “atankwadi.”

I am still proud to be an American today. I still consider “give me liberty or give me death”, one of my life’s mottos. But what 9/11 taught me on a personal level was that I would no longer do my best to assimilate into the white culture that purports itself to be American culture. Because that culture is ripe with fear. And I was taught, I was raised by my Nani Ji, to be Nirbhao and Nirvair. I consider “give me liberty or give me death” a life motto, not because a white man said it and I need to pucker my lips to his behind to not be killed. I consider it a life motto because the statement reminds me of the Nirbhao sakhis of the Sikh Gurus and Sikh heroes of yore. American values are my Sikh values in only so much as they reconcile with the morality of Mool Mantar. Mool Mantar does not teach one to live and respond to life events from a basis of fear, and so I embraced these fearless principles. However, it appears, the community to which I sought to and thought I belonged to, never actually did.