The media and politicians still lump together people from different parts of the world who practice entirely different religions. The result? Hate crimes

|

| Hateful comments are alienating, but the real problem is how it continues a cycle of other-ing. Photograph: FaceMePLS / Flickr via Creative Commons |

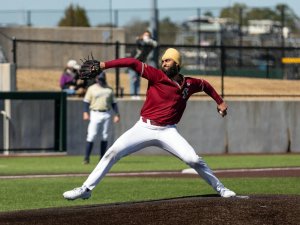

Tuesday 9 September 2014: In the last two months, three major hate crimes have hit New York City, the most ethnically diverse place in the United States. Last week, a man chased a Muslim American woman into oncoming traffic in Brooklyn while threatening to behead her. Earlier this month, a group of teenagers physically assaulted a Sikh American while hurling racial slurs like “terrorist” and “Osama”. In late July, a man shouted similar epithets at Sandeep Singh before running him over with his truck and dragging him nearly 30 feet.

In the nearly 13 years since 9/11, and now in the three months since the Islamic State (Isis) broadcast its brand of fear to the west, a new de facto racial category has crystalized: “the apparent Muslim”. The “apparent Muslim” has physical features supposedly similar to those associated with terrorism – brown skin, facial hair, turbans – but those who use the presumptive discrimination end up conflating racial and religious features. Anyone who makes assumptions about “the apparent Muslim” – and that is a lot of people, whether consciously or not – is effectively subsuming a number of communities, including Arabs and Sikhs who do not identify with Islam.

The accounts of the three individuals attacked in New York City reflect the typical hate-speech deployed during America’s “War on Terror”, which unleashed a new derogatory epithet for the apparent Muslim – “terrorist”. Other terms reflecting our current political situation have been regularly hurled at targets, including “Osama”, “al-Qaida” and “Taliban”. The victim of the hate crime in Brooklyn was threatened with a beheading – a threat that clearly reflects an angry and vengeful response to the inhumane beheading of American journalists by Isis.

The media plays a role in all of this, as hate crimes tend to spike following events receiving significant media coverage:

- In 2001, the FBI recorded 481 anti-Muslim hate crimes, over a 1600% increase from the year before.

- In 2010, the media closely covered the Islamophobic resistance to the construction of the so-called “Ground Zero mosque” in New York City, and the Southern Poverty Law Center documented a 50% increase in hate crimes against apparent Muslims.

- In 2014, violence linked with Muslims has been featured prominently in the news, from Syria and Benghazi to Isis and Hamas.

So it comes as little surprise that a recent study released by the Arab American Institute found that American attitudes toward Muslims and Arabs are becoming more negative.

Islamophobia related to current events is nothing new to this nation’s Muslims and “apparent Muslims”. Over 30 years ago, during the Iran Hostage Crisis, Americans suspected and targeted “apparent Muslims” of harboring anti-American sentiment and supporting Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Images of Khomeini and anti-Iranian rhetoric abounded in American media, and that political context informed the Islamophobic slurs that my Sikh-American father endured throughout the 1980s, including “Iranian”, “towelhead” and “Khomeini”.

As tensions increased in the Middle East, and in Iraq in particular, in the 1990s and the 21st century, people subjected to xenophobic sentiments, like me, noticed a shift in the derogatory names. Instead of being “Iranian”, like my father, I was called “Iraqi”; instead of being a “towelhead,” I was a “sand nigger”; instead of “Khomeini”, I was nicknamed “Saddam”.

The hateful comments directed toward people who look like me are divisive, and they are alienating. But the real problem is how it continues a cycle of other-ing – how Americans treat each other as guilty until proven innocent. Our ignorance leads us to lump together people from entirely different parts of the world (South Asia, the Middle East) and people who practice entirely different religions (Islam, Sikhism). We also fail to understand that not all Muslims interpret Islam the same way.

Just like every other religion, the extremists make up a small minority of the Muslim population; it’s not just unfair to take them as representatives of the Islamic tradition – it’s downright inaccurate.

The lack of nuance in our understandings of global cultures reflects the overly simplistic rhetoric of our media sources that feed us this information. Reporters are constantly skimming the surface to give us macro-level views, and while this broad-based approach has its advantages, it leads to misunderstanding serious issues, from white supremacy and domestic terrorism to Boko Haram and Isis. Until and unless we begin precisely accounting each challenge, we will continue to misidentify each other.

Politicians need to consider the impact of their rhetoric on more than their polling numbers – on the way it can can, ultimately, foster violence. And the media needs to gauge how to report on conflict and use images to explain both the news and illuminate the truth. Otherwise, many more innocent Americans will become targets for hate by those swept up in nationalistic or militaristic sentiment based on little more than xenophobia. The blame will start with the people we’re supposed to trust, but it will hurt every one of us.