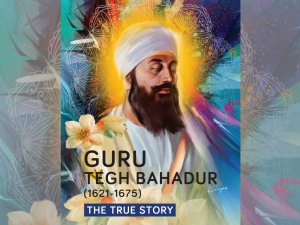

Guru Tegh Bahadur’s supreme sacrifice and the revelation of the Khalsa on Vaisakhi Day 1699, empowered the ordinary people to fight for their just rights and human dignity.

In year 2021, there is a convergence of egalitarian universal Sikhi values and the popular resistance, above communal divides, against unjust laws which affect the lives of hundreds of millions of Indian farmers and workers. For, dignity of labour (ਕਿਰਤ) is a core value of Sikhi.

Vaisakhi is the harvest festival and marks the culmination of the hard work of the farming community which is at the centre of Panjab economy and way of life now under threat from take-over by large corporations. Over 70% of the population of Punjab is directly or indirectly involved with labour-intensive agriculture.

Vaisakhi is associated with the emergence of the Khalsa (ਪ੍ਰਗਟਿਓ ਖਾਲਸਾ ), while this year, not just the Sikhs but all Indians, celebrate the 400th Parkash (birth) anniversary of Guru Tegh Bahadur. The people of India owe much to the supreme sacrifice of the Guru; an epic in the Age of Kalyug (ਕਲੂ ਮਹਿ ਸਾਕਾ) which started an unstoppable chain of events leading to the freedom of the sub-continent from a tyrannical regime by the end of the 18th century.

Despite some positive suggestions recently to commemorate the 400th Parkash anniversary of the Guru(1), Prime Minister Modi could have paid a fitting tribute to the Guru’s memory by early settlement of nationwide protests against exploitative farm laws which threaten to destroy the self-sufficient way of life and dignity of farming communities. No serious effort has been made to understand the spontaneous nationwide protests led by the Sikhs of Punjab against the existential threat to the lives of millions of Indian farmers and workers.

These three farm laws(2) would allow large predatory corporations to by-pass the state markets (mandis). Without collective bargaining power, the small farmers would fall prey to large corporate monopolies. It will become a buyers’ market forcing small farmers to sell at lower prices. The widespread concern is that their debt burden will increase and subsequently force them into bonded labour, a form of slavery common in some Indian states.

Nearly 800 million of the total population of 1.3 billion Indians owe their livelihood to agriculture. Paradoxically, while claiming to liberate farm produce selling, the new laws can leave small farmers at the mercy of large private corporations. State run food grain mandis (markets) will lose income and collapse. That will impact negatively on the whole economic structure and the infrastructure, including road networks, which support the Mandi system.

The farmers claim that an unregulated market will lead to loss of secure income for them because Minimum Support Price (MSP) has not been written into the new laws. Procurement through mandis (Agricultural Produce and Marketing Committees) will decrease massively causing their closure. Farmers will be driven to bonded labour – a form of slavery experienced by farmers in some states. (Bonded labour is a system in which lenders force their borrowers to repay loans through labour and one estimate is that there are 19 million Indians enslaved in such debt bondage.)

As pointed out by a Congress leader, it is unrealistic to expect the FCI (Food Corporation of India) to go to 15.5 crore farmers to purchase their farm produce. The government should make provisions in the law to allay the fear of farmers over the laws.

The state farming policy should ensure that all farmers get a minimum support price (MSP) for their produce so that they can live a decent and secure life. The MSP can be worked out by farming experts each year after taking into account all reasonable farming costs. Small farmers should not be concerned with complicated marketing mechanisms of how and where to sell their products. The state mandi system is a simple and certain way of doing that. Farm produce marketing can be liberalised without destroying small family farms and farming communities.

Of course, depending on shortages, there can be incentives to produce more of selected farm products through higher prices. These things can be worked out between agricultural experts and representatives of farmers at national and local levels through some sort of unified agricultural policy framework. Agricultural universities and research centres can be involved.

The Indian government needs to seriously reconsider the new farm laws which can destroy the livelihood and dignity of millions of Indian farmers. Punjab and Haryana will be hit the hardest and it will be most unfortunate if that leads to widespread social unrest.

For the above reasons, the freedom-loving farmers of Panjab were the first to wake-up to the trap which had been set for the farm communities across India. According to one source, “Sikh farmers have galvanized the country’s farming community and generated nationwide support. They will go down in India’s history as the frontline heroes of the farmers’ movement.” Another comment on a forum is that “the brave farmers have taken Sikh values to the streets for all the world to see and learn from. We should support the farmers, all the farmers of every faith and region in the spirit of Sarbat da Bhalla.” This comment sums up the link between Sikhi values and the farmer protests across India.

Traditionally, the Khalsa ideology restores dignity to the working fraternity through Guru Nanak’s trilogy principle of God-centred life of honest work and sharing. According to one writer, “Sikhi is actively shaping and strengthening the current farmer protests. Iconography of the Sikh faith (orange colours, the Khanda symbol) has a heavy presence both at Indian and diaspora demonstrations”.

The question asked is, why, when the government should have been totally focussed on Covid-19 pandemic, the ruling party chose to rush through the Parliament laws without consultation with the unions concerned? Bearing in mind that Panjab is predominantly a Sikh state, the question does arise if there was a communal political card being played by the ruling right-wing Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), otherwise fearing opposition from the Sikhs of Panjab. What the BJP politicians did not expect was that, led by Panjab and Haryana farmers, the whole of Indian peasantry would wake up to the grave threat to their livelihood and life-style.

In some ways parallels can be drawn between Sikh-led popular opposition to the “black” farm laws and their opposition to the “Emergency” of late PM Indira Gandhi in 1975, curbing civil liberties. During Indira Gandhi’s “Emergency”, the first mass protest in the country, known as the "Campaign to Save Democracy" was organised by the Akali Dal and launched in Amritsar, 9 July, 1975. Out of the 140,000 people arrested nationwide during the “Emergency”, 40,000 were from the less than 2% Sikh population. It is possible that the Sikhs were not forgiven for leading the opposition to the “Emergency” suppression of civil liberties and paid the price in 1984.

In Punjab, particularly, to quote a source, “…agriculture is rooted in the social base of everybody working on the farm with dignity. Thus, Punjab has evolved as a separate cultural entity within Indian federalism. The state produces a lot of wheat and milk, and the notion of ‘Kar Seva’ (labour service) even in gurudwaras has attracted global attention.”

As a politician and one who knows the Sikh tradition only too well, P.M. Modi should have realised much earlier that the farmer protests were for a just and popular cause and would not go away. In fact, political tactics, the gimmicks and the threats would only strengthen the resolve of farming community leaders. As one who has spent considerable time in Panjab, he should have learnt from the Sikh tradition of morchas so admired by national leaders like Mahatma Gandhi during the colonial days.

P.M. Modi could have won over India’s farmers and the Sikhs and come out stronger. He could have listened to the people’s voice, withdrawn the “black laws” to start a meaningful dialogue with the unions concerned to safeguard the livelihoods of the farming communities. In the current situation, his plans for celebrating Guru Tegh Bahadur’s 400th Parkash can be misunderstood as another political move to weaken the farmers’ resolve.

Delay can only lead to unwelcome outcomes and no solutions. As Giani Harpreet Singh said, “It is a matter of concern. An atmosphere of communalism is being created in the country and minorities are being oppressed under the patronage of the government. Seeds of hatred are being sown in the minds of people of one religion against those of the other.” (TNS 3 April, 21)

The Jathedar has compared the situation with the socio-political environment prevalent during the Mughal era. With that reference back to the Mughal period, the Jathedar’s appeal for unity in the Khalsa Panth carries a certain urgency this year when India is celebrating the arrival of the Guru whose unique martyrdom upheld dharam – the righteous cause.

It is not too late for Prime Minister Narendra Modi to commemorate Parkash 400th of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Hind di chaardar, by listening to the farmers and workers of India.