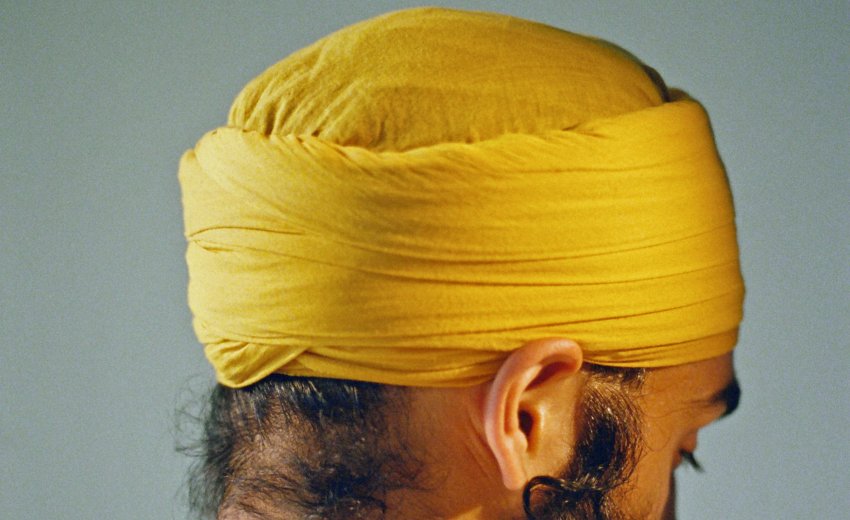

I am a Sikh.

A turban is an article of faith for the Sikhs. It signals honesty, service and compassion to those in need. But the opposite has been perceived in our country, especially after 2001.

Many of my fellow Americans continue to mistake Sikhs for those they aren’t, simply because of their appearance.

From bullying in schools to discrimination in the workplace to becoming victims of violence, Sikhs continue to suffer because fellow citizens connect their appearance to terrorism.

As a result, more and more Sikhs are practicing their faith without its most visible article — the turban and the unshorn hair under it.

The first American killed by a fellow citizen in vengeance after 9/11 was a turbaned Sikh in Mesa, Arizona on Sept. 15, 2001.

Last September, in Texas, a routine traffic stop cost turbaned deputy Sandeep Dhaliwal his life. Another turbaned Sikh in Tracy, California, Paramjit Singh, was stabbed to death during a routine walk in the park last August. The list of such brutalities against turbaned Sikhs goes on.

Even America’s largest employer, the military, for decades did not allow Sikhs to serve with their articles of faith despite their rich and proud warrior history and inspiring record of service in the armed forces of various countries. More than 80,000 Sikh soldiers laid down their lives serving alongside Allied forces during World Wars I and II.

In 2017, after years of lawsuits and pressure, the U.S. Army changed its policy to allow observant Sikhs and members of other religions to wear beards and head coverings provided permission is applied for in advance. The NYPD now allows Sikh officers to wear turbans, joining a few other local law enforcement agencies with similar policies.

Yet, while some Sikhs have fought long and hard for the right to wear the turban, others have voluntarily abandoned this tradition, perhaps because of its possible impact on their personal or professional lives.

For example, here in Delaware, there are several prominent Sikh doctors but not one who wears a turban — despite their towering presence on the trustee and management boards of the state’s two gurdwaras, which are Sikh temples.

For Sikh women, life is easier on this count because a turban is optional for them. However, even without a turban, belonging to the Sikh faith or having brown skin can impede or even disqualify their participation in mainstream activities.

This is something Nikki Haley (nee Nimrata Nikki Randhawa), former governor of South Carolina and U. S. Ambassador to the United Nations, reportedly learned in her hometown of Bamberg, South Carolina, when she was 5.

Nikki’s parents had attempted to enter her in the “Miss Bamberg” contest but her application was rejected because she did not qualify for either crown: black or white. Eventually, a few years before entering politics, she changed her religion from Sikhism to Christianity.

It is ironic that in some parts of the world, the turban is viewed as a sign of security, not a threat. In India, the Sikh homeland, a single woman, or anyone who feels insecure, is more likely to hire a turbaned Sikh driver because of their well-known dedication to serving the needy and protecting the weak and vulnerable.

So in 2020 and beyond, how can Sikhs and other religious groups correct the misconceptions that appearances generate in those who are ignorant, hateful and impulsive?

Only through education and participation in schools, workplaces, houses of worship and communities — and a strong media presence — can observant Sikhs encourage and expect understanding.

Let’s hope that someday all Sikhs can base their decision to wear or not wear a turban purely on personal choice and not on external influences or threats.

Charanjeet Singh Minhas is a Delaware resident and founder and CEO of Tekstrom Inc. in Wilmington. He is also chairman of Delaware Sikh Awareness Coalition.