First things first. Most of us connect with one religion or another; hence, we treasure some deeply held practices. I am a Sikh. You need to know this so that my biases won’t shock you. Today I take on a question that is larger than life. I attack this Gordian knot, not to destroy it, but to explore it.

Like many Sikhs I, too, have proudly and forcefully asserted that Sikh faith is universal and its scripture, Guru Granth sahib, is the unparalleled source document on interfaith dialogue. Inherent in this is the idea that some faiths are perhaps not always so; my evidence for this inference rests in the many inter-religious wars that dot our historical landscape.

But every religion asserts that its message is unmatched and superior to many others that also exist. Doesn’t this set up a never-ending war between the faiths of mankind? Allow me first a brief detour; hopefully, to be better equipped to parse the issue further.

It is self-evident that humans at birth are fragile. They depend on collectives, small or large — families, clans, communities, even nations — to thrive. Collectives need a code of common behavior that is not easily or casually challenged. In time, collectives become lifestyles, deeply intertwined with a people’s religious underpinnings of belief, language, music, culture, cuisine and practices. Much as good fences make good neighbors, fences of lifestyles define communities and the borders that separate them. The defining characteristics of communities are more important than any one individual’s behavior.

Despite the fences, we also need to communicate with our neighbors. Not an easy task. Rare people — visionaries and prophets — recognize that humans need a larger message for humanity. And that gives us the many religions, each originally connected to a particular ethno-geographical community. Is this a fair summary of “Tribalism?” Fences are useful when they do not become hermetically sealed compartments that isolate neighbors. A tribal reality is never universal.

If I have learned anything from a lifetime in academia it is that no matter the topic, all teaching must be framed in the cultural and linguistic context of the student. Similarly, a prophet must cast his message in the cultural and linguistic context of the people or the lesson is lost. This golden rule brooks no exceptions.

Here then two primary needs are in conflict. The visionary prophet aims to construct a reality that is inclusive and universal – one that appeals to any and every listener — even strangers are welcome to the cause. But the message is organically connected to a specific culture whose people have unique customs, music, language and cuisine. That’s where a message takes life. Strangers coming in would find significant differences; that makes the message a tad limited.

We often cite chapter and verse from Sikh history, tradition and the Guru Granth to nail the idea that Sikhi is a universal model of life. History tells us that the Founder, Guru Nanak, did not stay entirely within or even close to the perimeter of Punjab, but traveled widely across and beyond the Indian Subcontinent – south to Sri Lanka, northwest to the Middle East, including Mecca, Iraq and nearby territories, eastward to Assam and North to Kashmir and Tibet – just about much of the known world of his time.

He spoke of Ik Oankaar, an alphanumeric that he designed where “Ik” is the first numeral “One” and “Oankar” meaning “Doer" or "Creator” that comes from Sanskrit. Ergo, a single unitary Creator common to all -- Jews, Christians, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Parsees… or Brand X. A partisan God would then be a lesser god, not worthy of worship. In Ik Oankaar there is no room left for differences in caste, creed, color, gender, race, national origin, religious label or similar limiting ideas.

The repository of Sikh heritage – Guru Granth – comprises the writings of six of the ten Founder-Gurus of Sikhism. It was assembled by the Gurus themselves, with minimal possibility of unauthorized compositions sneaking into the 1430-page tome. Also included were selected compositions of Hindu and Muslim saints of the era whose writings found resonance with the Sikh message. Some of them came from low castes. Remember that in the India of that time (about 550 years ago) high and low caste Hindus would not ever break bread together or be caught on the adjoining pages of the same holy book, but in Sikhi that’s where they are.

Had Jewish or Christian writings been widely available at that time, I am certain, they would have found more inclusion and commentary. The Guru Granth does not brand any people as evil or sinful even though it has some critical/analytic comments about some widespread practices and interpretations in Hinduism and Islam – the two major faiths in India at that time.

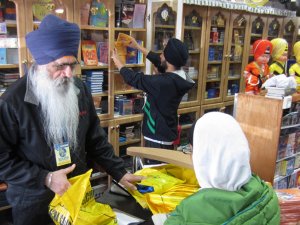

A unique practice that Guru Nanak started is Langar, the serving of a simple vegetarian meal at every Sikh service. It is prepared and served gratis by men and women volunteers to everyone, poor or rich, high or low of caste and worldly rank. This mighty dagger thrust into in caste driven cultures exists even today all over the globe. Langar exists as a symbolic and historical reality of equality wherever there is a Sikh community, no matter how small.

This, not so brief take of mine, makes a clear case for Sikhi as a universal religion. But the devil, as they say, is in the details. Contradictions emerge not from the teachings but human imperatives, insecurities and the tendency to circle the wagons, batten the hatches and erect impermeable barriers in the face of threats, real or imagined.

An interminable gulf separates principle from practice. This is true in any faith discipline in this wide world, and Sikhs are no exception. If our contradictions appear less glaring it’s because we are a comparatively young discipline as opposed to many others. For example, a wide gulf exists between our teachings and our actual practices in matters of caste and the place of women. On both counts the message is direct and clear but our practices are not.

I offer a few examples of such trivia that chew at the periphery of our traditions.

The spiritual writings of the Sikhs have always been freely available to anyone, whether Sikh or not. Many have also been reproduced in scripts other than Gurmukhi. But a growing movement rejects such initiatives – as if Gurmukhi is a holy script and others are not. It seems to me that holy is the message not the script that carries it. Languages deserve respect because they carry the human narrative through defeat and triumph – the narrative is our story.

Some practices seem to focus on if, and how, to maintain the Guru Granth in a home, how to transport it and who is entitled to keep one. To me these are unfortunate and divisive developments. I point out their similarity to Christian practices when the Council of Tarragona in 1234 banned the possession of the Old and the New Testaments in the Romance Languages and ordered that anyone who had them must turn them over to the local Bishop within eight days. This decree lasted a couple of centuries. Sometimes the diktats that come from the Akal Takht speak in similar vein. The idea of respect or its loss for the Guru Granth becomes central, whereas I think the respect will come from reading and engagement with its contents and cannot come from enforcement. Certainly, we Sikhs should never travel the unfortunate path of 13th century Christianity. Surely that reduces the idea of universality.

I have seen life-threatening disagreements on letting a non-Sikh, or a lay Sikh, and any women, Sikh or not — perform some of the so-called ‘priestly’ functions within a Sikh place of worship. I leave such inanity without further comment.

The place of the English language within a gurduara often garners criticism. This, despite the fact that more than six languages and many, many local dialects are found in the Guru Granth itself. We have started referring to Gurmukhi-Punjabi as holy because the Guru Granth is traditionally penned in Gurmukhi script and Punjabi is the language of Punjab – the homeland of the Sikhs. Again, I ask Sikhs to marvel at the worldview of the Gurus and their writings before such paranoia.

Sikh teaching does not condemn any religion even though it questioningly points to some widely visible practices of many. Nowhere does Sikhi ever declaim: ‘Come join our way for this is the only true path.’ Unfortunately, many faiths do seem to follow that route. Remember that we cannot judge if such thoughts were originally uttered by the prophet, nor may we easily see the historical realities then, or if they entered after the Founder-prophet’s life. Nor can I aver if such thoughts are a misreading of the mind of the prophet or a mistranslation etc. Many are the times in the streets that someone has asked me to join his or her faith – the only true faith, as he/she put it. Briefly the teaching of the Sikhs to non-Sikhs is to thoughtfully discover the virtues in their own faith disciplines.

I personally feel that none of the founders of any faith would make a claim of exclusivity in his lifetime. Why? Because exclusivity creates tribalism, not a universal paradigm. I feel that such exclusivity entered the narrative when the clergy faced opposition and were not prepared for commonsense dialogue, conversation and tolerance. Without these attributes in a community, self-governance disappears and the system becomes akin to a kakistocracy – rule by a corrupt, unscrupulous minority. I have pointed to some gaps between Sikh teaching and its practice. Such gaps are universally found in every religion. Why? Let me explain via a detour.

This has no bearing on my political label, whatever it is. Not so long ago I caught Paul Ryan, the current Republican Speaker of the House being interviewed on the tube. He commented that the election period highlighted the many shades of opinions that existed among Republicans. Given the acute fissures among hard-core Republicans, the dream of a unifying idea may be fiction and fantasy. Then, he offered what I thought was a surprisingly mature thought – that the core requirement for unity is principles not practice.

Keep in mind that religious communities and centers exist for imperfect people who are on the path with varying degrees of success, sincerity, faith or understanding. We need to nurture the path, not diminish the follower. This is what transforms sinners into saints. Teach the principles and watch the practices flower; that’s the idea.

I believe that Sikhs should never mount an aggressive agenda to make others convert to our faith, though we would clearly welcome them to the cause.

Proselytization is not the answer; it only diminishes others.