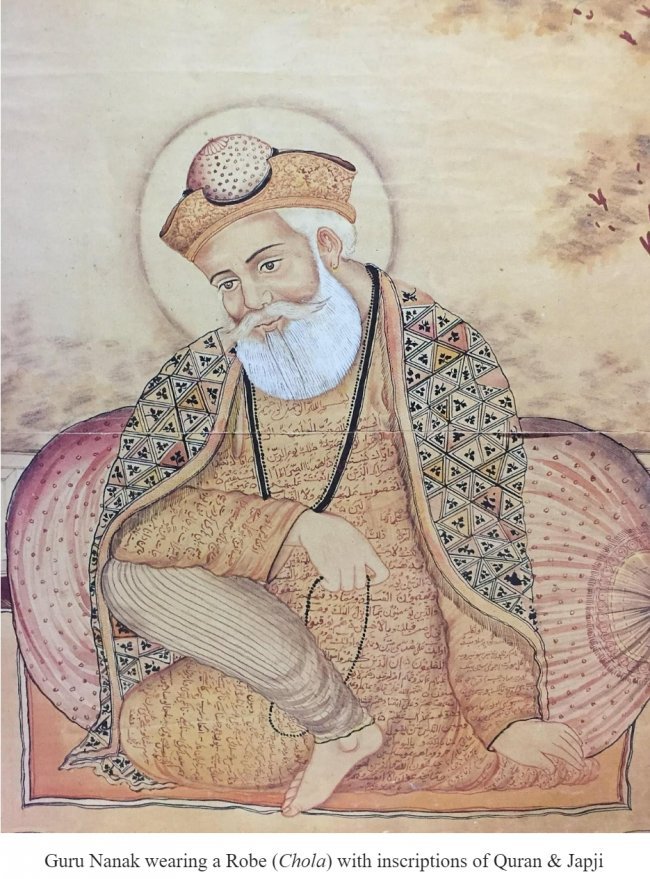

Introduction: In June, I got a phone call from Lahore. The caller introduced herself as Nadhra Khan. She was asking for some information about the robe (chola) of Guru Nanak with inscriptions of holy Quran written all over it. I knew about this sacred artifact and its custody with the Bedi family of Dera Baba Nanak but was oblivious of its history and origin. I tried to contact some Sikh Chair professors of past and present but none was able to answer her query satisfactorily. Nadhra told me that this robe has Japuji Bani written over the sleeves of the robe while the remaining part has Quran verses (ayats) written all over. Mostly, Sikh scholars are not aware of this fact and their information is based on speculation.

Dr Nadhra Shahbaz Khan holds a Masters in Graphic Design and a Ph.D. in History of Art, both from Punjab University, Lahore. She teaches art history and serves as the Director Gurmani Centre for Languages and Literature at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan. A specialist in the history of art and architecture of the Punjab from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century, her research covers the visual and material culture of this region during the Mughal, Sikh, and colonial periods.

After this brief telephonic discussion, my curiosity to learn about her work on Sikh Art and Architecture increased. My search on Google proved to be helpful. I found her credentials of an academic with many accolades by prestigious institutions, viz, research fellowships at SOAS, London (Charles Wallace 2010–2011), INHA Paris (2015), Princeton University (Fulbright 2014–2015), Oxford University (Barakat Trust 2014–2015) and the Lakshmi Mittal South Asia Institute, Harvard (2021-2022).

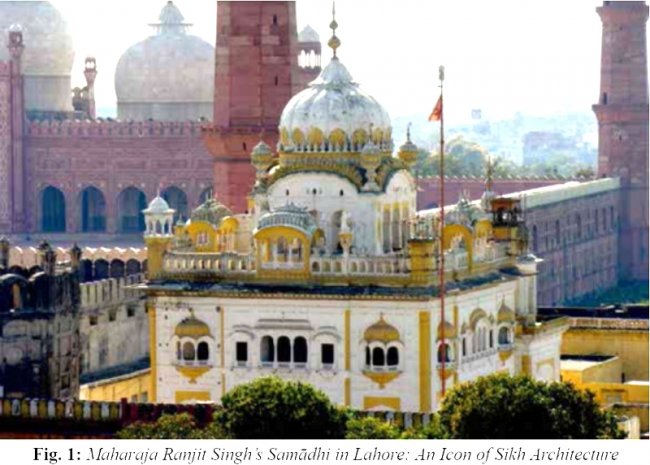

Sikh Art and Architecture of Ranjit Singh Era: Nadhra is a specialist in the history of art and architecture of the Punjab from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century, covering the Mughal, Sikh, and colonial periods. Her book titled Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Samādhi in Lahore: A Summation of Sikh Architectural and Decorative Practices and a website (https://www.sikhvirsa.org.pk/home/) that features Sikh artifacts in the Lahore Fort’s Sikh Gallery, have successfully brought Sikh art and architecture in the limelight at the global level.

I consider the greatest contribution of Nadhra is to change the colonial narrative of the Sikh art. In her interview recorded in “Guftugu”, the MGSHSS Newsletter of 2018, she is emphatic about her passion to promote Sikh art. She ridicules Thomas Henry Thornton, a British civil servant of pre-partition India, who wrote in his book: “There is no originality of Sikh art and architecture claiming that the Sikhs were looters; that Ranjit Singh did not have any aesthetics as he was illiterate and ‘of martial habits’; that all he did during his rule of forty years was to disfigure Mughal monuments and rob them of their marble and red sandstone to embellish the Golden Temple”.

Further, her ridicule of Thornton changes into condemnation of the British: “This misguided narrative of Thornton has seeped into popular imagination and has rendered the entire history of Sikh contributions to South Asian art and architecture moot. My passion project is to investigate these contributions and set the record straight. I am sure my findings will inevitably help save some extremely important monuments and other artifacts in the Punjab and elsewhere that have been suffering from neglect and disregard ever since the British occupation of this land in 1849 (after annexation of Sikh Raj of Ranjit Singh)”.

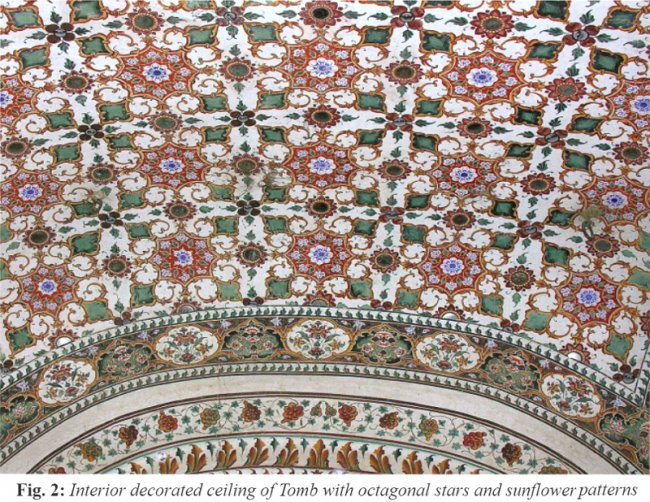

Nadhra writes in her book: “The construction of samādhi was begun by Kharak Singh, the eldest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and completed several years later, under the British rule. The Maharaja’s samādhi is located next to the Lahore Fort, where the Maharaja lived during his reign of forty years, and was the last state funded grand project of the Lahore Darbār before annexation. As the high point of nineteenth century Sikh architecture in the Punjab, second only to the Golden Temple at Amritsar, it has fine examples of carving in red sandstone, white marble and wood, pietra dura inlay in white marble with colored and semi-precious stones, mirror mosaic and frescoes, almost all preserved in their original forms”. The focus of this book is on the architectural embellishment of the building and the author has shown her magnanimity to bring out all details of interior and exterior of samādhi in minute details. I think she is the first author to highlight the unique features of Sikh Art and Architecture in her book.

In her concluding remarks, Nadhra brings out the originality of Sikh Art and Architecture into focus: “The frescoes are significant for at least three reasons: they are dateable, carry elements of change in the painting style of the period, and reflect socio-religious practices of the nineteenth century Punjab. This study shows that although the basic repertory of the artisans remained similar over the centuries, modifications occurred with changes in patronage and circumstances. More importantly, it identifies distinct Sikh period features, proving that Sikh architecture is not an idle imitation of previous styles but a definite development with unique characteristics of its own”.

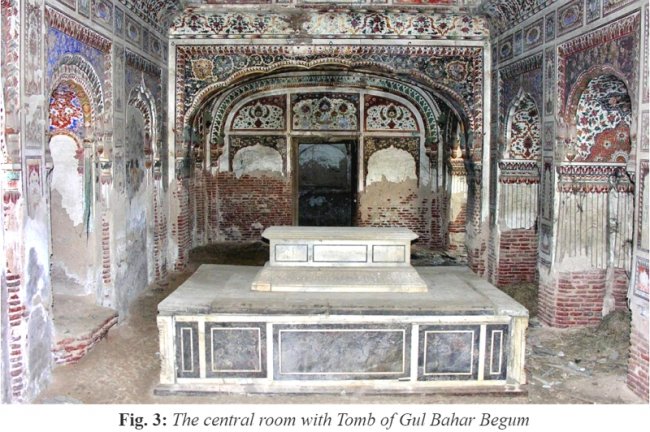

Decorative Sikh Art on Tomb of Rani Gul Bahar Begum: In her essay “The Secular Sikh Maharaja and His Muslim Wife: Rani Gul Bahar Begum”, Nadhra gives minutest details of Maharaja’s marriage with this dancing girl in 1832. He got separate mosques constructed for his Muslim Ranis and allowed them full freedom of practicing their religion. Gul Begum caught the fascination of Maharaja when she joined the troupe of dancing girls called to entertain Lord William Bentick at Ropar (Roop Nagar) in 1831. All the girls were paid Rs. 7000 each but Maharaja doted on Gul Begum and selected her as his Rani. Khalsa Darbar archives report that the Maharaja offered lakhs of rupees, elephants, horses, and all the jewels in the treasury, except Koh-i-Noor, as wedding gifts to his new bride. The honeymoon of Maharaja with Gul Begum continued for a few months before they returned to Lahore in full regal splendor showering gold coins over all residents. She survived Maharaja for many years after his death in 1839. She was awarded the highest annual pension of Rs. 12,380 among the widows, by the British government after the annexation of Khalsa Raj in 1849.

All the Ranis were expelled from their living quarters in Lahore Fort in 1849. Gul Bahar Begum went to live in her estate with a beautiful garden planted for her leisurely strolls. She had no issue and adopted Sardar Khan as her son after Maharaja’s demise. She planned to construct her tomb while living. Nadhra has given details of architecture and paintings inside her tomb which remains out of reach of historians and public in Lahore as it is a private property.

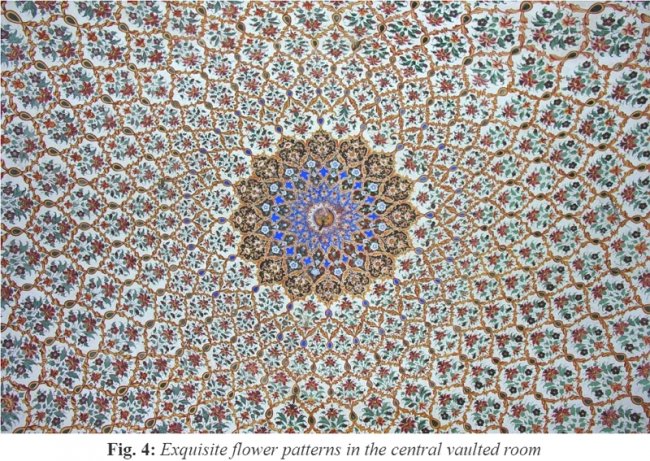

Nadhra gives a beautiful professional description of Rani Gul Begum’s Tomb: “It presents a paradisiacal environment created with masterpieces of fresco work. Images of flowers and fruit are painted in a variety of styles on almost every inch of the interior space. These motifs cover different parts of the walls and ceilings in carefully calculated and aesthetically pleasing compositions. Starting with leaf-motifs at the bases and capitals of the piers and engaged columns, they gradually increase in volume and density as they cover the carved springers, entwine around the cusps of arches and spread over the spandrels and soffits. On top of these are cartouches framing exquisitely painted dishes laden with fruit interspersed with vases carrying bunches of flowers. The soffit of the dome on top of the white marble cenotaph is a masterpiece of nineteenth century decorative patterns. Designed as a shamsa or sunburst, this radial pattern composed of strapwork and flower motifs emanates out of a densely packed medallion-like motif set against deep tonal values. As the pattern branches away from the center, the background color turns white to enhance the yellow-gold strapwork with silver drop-shapes imitating mirror-mosaic, and crimson flowers complete with their green leaves and stems. The abundance of flowers and fruit, of plants and leaves in cheerful colors would have been a natural habitat of birds of equally gay plumes. Respectfully following the Islamic injunctions against representing living creatures, Gul Begum’s worldly paradisiacal abode happily stands waiting for the birds of paradise to fly in and break the silence with their sweet chirping”.

Concluding remarks of Nadhra about the quality of frescoes inside the Tomb are interesting: “Wall paintings inside Rani Gul Begum’s Tomb are among the best examples of the very few surviving Sikh period frescoes. Commissioned by the Rani, they are specimens of excellent craftsmanship and appear to have been executed by best available artists. Their fineness is comparable to other royal commissioned works in Lahore like the main hall of the Sheesh Mahal (palace of mirrors), Naunihal Singh’s haveli (pavilion) and Maharaja’s Samadhi (funerary monument). Gul Begum’s Tomb paintings are also significant because they are dateable, present a well laid-out ornamental program and were in their original form without retouching when photographed in 2007 by her”. Nadhra is worried that these paintings are in a state of neglect and call for immediate preservation and conservation. I wish some well wisher of Sikh heritage of Art and Architecture of Maharaja Ranjit Singh Era in Lahore listens to the clarion call of Nadhra!