By Sukhjit Kaur Khalsa and Lakhpreet Kaur

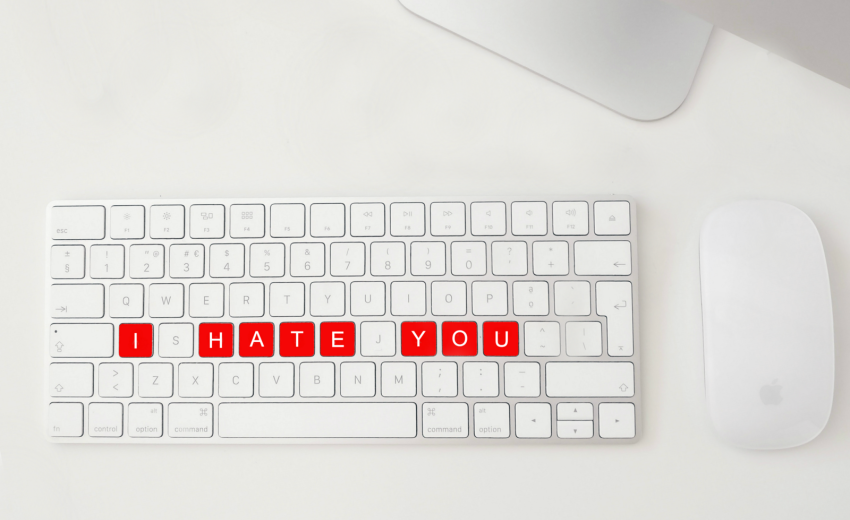

The internet can be a wonderful tool to bring together Sikhs across the world. But it can also be a destructive tool that tears people down. We have noticed that many Sikh women activists have been harassed (on and off the internet) by the very panth they are trying to serve. In this series of “Sangat Harassment” we interviewed several Sikh women activist to learn about how the panth responds to their leadership.

This first article address how prevalent and destructive harassment against Kaurs is within the Sikh panth. The second part of the series, “Why Does My Sangat Harass Me?” we explore possible reasons for the negativity faced by these women and the reasons people bully. The last article, “How You Can Support Kaur Activists,” discusses what these women need and want from the community to feel supported, along with presenting steps for positive change.

When we started our digital seva, we both received mixed reactions from our friends, family and the larger Sikh community. Lakhpreet runs Kaur Life and Sukhjit is a spoken word poet, playwright and performer. Both of our work is very online-oriented; it’s how we build community, share ideas, and learn from other Sikh women. While it has been wonderful to connect with sisters across the globe, the internet has enabled the dark underbelly of the panth to be exposed. We get cyber-harassed by other Sikhs a lot.

In talking to other Sikh women, we realized that we were not alone in experiencing this. So, we decided to talk to several Sikh women about their negative and positive experiences when engaging in seva. (Many of these women have used pseudonyms so they make share freely and avoid further persecution.)

We write this article to help create an environment of collaboration, growth, learning, and support. We also know that there is strength in numbers and we want to leverage that for good. We want the larger Sikh community, including Sikh men to realize that cyber-harassment isn’t simply an experience of “just a few of women”, but many people are going through this challenge, whether they are Instagram superstars to the average activist with a small following. We want to start the conversation about what it means to be a supportive panth, and what we can do to encourage each other in seva and to walk on the Guru’s path. Without such support and love, the fragile ecosystem of our families and families to-be will shatter. Strong Kaurs can help change the world but unsupported, degraded Kaurs might not want to keep struggling.

WHAT IS HARASSMENT?

When it comes to harassment, specifically cyber-bullying, intentions are not positive. According to SikhNet program director, Ek Ong Kaar Khalsa Michaud cyber-bullying, “…means to have your person be disrespected in violent or near-violent ways with an intention to create trauma. Bullying does not engage in debate about ideas. Bullying aims to break the spirit of the target, so that they have no inner strength to speak, or be present, within whatever community in which they are participating.

Bullying is a kind of killing – because it seeks to destroy the credibility of the target, and even that person’s very existence. The act of bullying tries to erase the target’s unique identity – forcing change upon it, or if the target won’t change, social banishment. That social banishment takes the form of ignoring the person at best; continually ridiculing and stifling the person; or threatening or taking violent action against the person at worst.

Social media and the World Wide Web have amplified this dynamic of bullying. As public figures in the cyberspace, the work we do has the potential to impact so many people around the world. But the Catch-22 is that we also are vulnerable to bullying on a scale never experienced before. Far broader than what might happen in any one particular physical community.”

WHAT ARE PEOPLE HARASSING US ABOUT?

BECAUSE WE AREN’T MEN

A big theme we found when talking to Sikh women about the harassment they faced is that they are being treated unfairly or rudely simply because they are not men.

“I’ve picked up that when dealing with committee members or other community leaders, they are more likely to receive the same idea from a Singh,” said sevadar Balmeet Kaur (pseudonym). “The transmission of an idea by a Singh is received differently than from a Kaur.”

Balmeet Kaur’s observations were echoed by a leader in a prominent Sikh non-profit organization, Leader Kaur (pseudonym) who said, “At times I’ve been dismissed or discounted or there has been an assumption that a man must really be running things.”

Sevadar Kaur (pseudonym) shared an all too common story about being ignored because she is a woman. “I spoke in front of an entire gurdwara sangat in both English and Punjabi. Afterwards, the president went up to my husband to ask him follow up questions about my speech. My husband kept telling him, ‘I have no idea how to answer your questions I’m not part of the organization, you should ask my wife.’ But the president refused to talk to me. I answered his questions as they were directed to my husband, but he didn’t even look at me.”

While these examples are blatant forms of sexism, the hidden form of micro-aggressions are experienced by Kaurs more often. A micro-aggression is exactly what its name states, “micro” = small and “aggression” = hostility: small hostilities. Micro-aggressions are demeaning implications and subtle insults. It could be verbal or non-verbal “put-downs.” These actions are so subtle that often times the offenders don’t consciously know that they are behaving in a mean way and the receiver can’t exactly identify what behavior is making her uncomfortable.

“I deal with micro-aggressions more than I deal with outright negativity,” said Balmeet Kaur.

Things like sexist language (ie: a katha or gurdwara speeches being directed at Singhs only), victim blaming (ie: people blaming a Kaur for being raped), tone policing (ie: a Kaur being told she sounds bossy versus a Singh who is considered assertive), language policing (ie: young women being raised to speak quietly or not speak often), mansplaining (ie: a Singh interrupting a woman to explain what she was already explaining at camp), and period shaming (ie: gurdwaras unjustly prohibiting women from doing seva while menstruating) are examples of micro-aggressions that keep women down.

BECAUSE OUR BODIES AREN’T GOOD ENOUGH

Kaurs also face a lot of body policing. Body policing is criticizing a person’s appearances and/or offering unsolicited advice about them.

“I’ve had to question what I’m wearing. One of my colleagues got yelled at by a constituent because of her attire once, and other women on our team are often criticized for their outfits. I’ve noticed that people judge me as a Sikh leader based on how I practice Sikhi,” said Sevadar Kaur.

Dr. Kaur, who wears a dastar, said the negative feedback she gets from the Sikh community is based on whether they view her as “worthy”. “I received a lot of pushback and critique from peers who called me judgmental because of how I looked.”

Others make it their mission to criticize a woman’s private choices regarding body hair and clothing. For instance, many times Sukhjit Kaur Khalsa has been told, “Your body hair is disgusting and you shouldn’t be showing it off.”

Gagan Kaur recently posted a story on Instagram where she shared the rude comments other Singhs have been leaving on her photos and she said, “It is clear to a lot of women that some men feel they have ownership of our Amrtidhari and/or dastaar wearing bodies.”

This type of policing isn’t specific to men, as many Sikh women will judge, comment, and police each other as well. The presumption in these cases is that a woman’s body is not her own and that she should defer choices to the larger community, whether or not the community’s general consensus is in line with gurmat or not. Furthermore, it serves to undermine a woman’s sovereignty as it implies that she is not competent enough to dress or groom herself according to her own standards.

BECAUSE OF SNAP JUDGEMENTS

One of the biggest challenges facing Kaurs are the snap judgements people make about them.

Harleen Kaur says that people have, “called me too radical for what I said, or simply made assumptions about who I am based on their few second analysis.”

Jo Kaur has also felt push-back in this form. “For instance on social media, if they didn’t like my answer, I was immediately blocked or written off… It was a harsh response from folks who don’t know me personally at all.”

Small judgements can sometimes escalate to violent threats. For instance, several women interviewed said they received death threats while engaged in Sikh activism. Ek Ong Kaar Khalsa Michaud shared her experiences saying, “factions in the Sikh community who are ‘yoga-negative’ ” quote her out of context, ridicule her personally, and attempt to discredit her Sikh work on online forums.

“As part of a campaign to discredit me, somebody once created a fake marriage video showing ‘me’ marrying another Sikh man in a fire ceremony at a Hindu temple. The image of the woman who was supposedly me was dressed in full bana with a turban, but her face was blurred out.

And my current all-time ‘best’ story: As I was preparing to self-publish the Sukhmani Sahib translation, receiving a veiled threat telling me that if I did not have my translation approved by five nihang Singhs who lived full-time in a Gurdwara, I might end up losing my life.”

In general, it seems like the people who engage in bullying are unwilling to engage in constructive, thoughtful conversations when a disagreement arises. Instead, they resort to personal attacks and threats.

Lakhpreet Kaur also receives regular hate-emails that include comments like, “You are a cancer to Sikhi”. “You’re too religious.” “You’re not religious enough.” “You need to shut this down.” “Kaur Life is a waste of time.”

“It’s very hurtful because I am not trying to ‘ruin Sikhi’, I just want to help. I have always invited these people who write in anger to submit an article expressing their point of view, but they not once has anyone accepted,” said Lakhpreet.

It is clear that cyber-harassment within our community is rampant. Women across the world, working in different areas all face bigotry and frequent harassment. This unwanted, aggressive behavior involves a real or perceived power imbalance. While some keyboard warriors are intentional in their behavior, others might be harassing Kaurs without even being aware of it or the consequences.

RELATED ARTICLES:

1. Read “Why Does My Sangat Harass Me?” to understand why people may be acting the way they do.

2. Read How You Can Support Kaur Activists,”