JOURNEYS OF A LIFETIME

From Lahore to Amritsar

|

| Fatima Bhutto at Amritsar's Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple). Photo: Michael Turek |

October 09, 2015: Tonight, I packed my bags for a journey I have made over and over again in my mind. Two countries, two cities, partitioned by history and imagined distance, 68 years ago, over two days in August. I don’t have a favourite number or anything, but two seems to show up an awful lot as I plan to cross the border between Pakistan and India, stepping from Lahore over to Amritsar. Two. But how do you journey across one Punjab? Is it travel if you constantly feel like you’re at home?

Lahore

As the PIA plane (replete with old carpets, seats without video monitors and that special PIA smell) circles the regal city of Lahore, I look up at the solitary television hanging on the wall. Lahore is marked by a small white diamond. Across a jagged line from it, but so close they might as well be spooning, lies Delhi, and above them, white mountain peaks. “Disputed territory” the text reads.

Though it was ruled by a constellation of monarchs—Shahi, Ghaznavid, Mughal, Sikh—legend says Lahore was founded by Prince Loh (Lav), son of Sita and Ram, over 4,000 years ago. But legends take the most beautiful stories and distil them until all that remains is the most beautiful, but not necessarily the most true. This garden of kings is probably only half that age, and though it was born of so many people and beliefs—Hindu myths, Sikh treasures, Muslim splendour, it was even the heart of the Punjab under the British Raj—you will see only what you wish to.

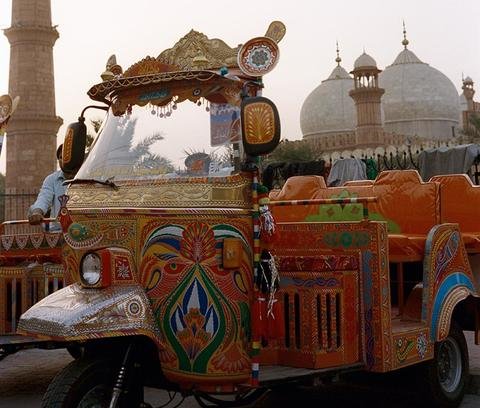

|

| A decorated rickshaw on Lahore's Food Street. Photo: Michael Turek |

On my first night, I drive down Mall Road, so much of it like Delhi’s Connaught Place—the wide avenues, the bricks, the trees. I see a flicker of lights brighter than car headlights. A monument, I think, scanning a city I haven’t been to for 10 years, even though I live in Karachi, less than two hours away. But as we pass a grassy patchwork of yellow flowers, I see it is Jinnah, the nation’s founder, lit up in profile by a lattice of starry lights. But this is everyone’s city. Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, was born across River Ravi, in Nankana Sahib, the district and the gurudwara named after the holy teacher. Bhagat Singh, hero of the freedom movement, was jailed and martyred here. It was in Lahore that Nehru sounded the bell for India’s complete independence from the British, in 1929. And it was from the grounds surrounding the Minar-e-Pakistan that the Muslim League called for the formation of Pakistan, in 1940.

Everyone’s city.

Sohail, my guide through Lahore’s walled city, steers me through the incredible Lahore Fort. Here, in the Diwan-e-Aam, teenage boys in tight jeans pose for selfies in front of Mughal Emperor Jahangir’s white marble throne. There, on the walls of Emperor Shah Jahan’s Khwabgah, or bedrooms, people have written their names and phone numbers on the walls. “I love you” is what most have scratched in ink, along with their details. Nearby, a fresco of Radha and Krishna, painted during the Sikh period, stands high on the walls. Sohail is at his finest narrating love stories; as we stand in the Sheesh Mahal, or crystal palace, he really gets into the swing of things. “You say you love me,” he narrates, providing the voiceover for Mumtaz to Shah Jahan. “Can you bring me the stars? Will you bring the clouds at my feet?” He waves my phone at the ceiling, and the light makes the intricate mirrors sparkle. “He brought her the stars,” and then, waving at the floor, continues, “and cloudy marble for her to walk on.” That is why “sabse achha Shah Jahan,” he pronounces. “He made India beautiful, he was good at architecture, good at romance and a very, very good husband.”

Nearby lies the Badshahi Mosque, which Aurangzeb had built out of pink stones from Jaipur. Just across lies the samadhi of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Lion of Punjab, and in Gurudwara Dera Sahib, the remains of Guru Arjun, the fifth guru of Sikhism. As we leave the Badshahi Mosque, Sohail points out the small tomb of Allama Iqbal, tucked next to the grand mosque. We pause until someone recites the poet’s famous words. “Better than anywhere in the world, our India. We are the nightingales, it is our garden home.”

How, I wonder, did that become India, and this, Pakistan? Wagah

Wagah

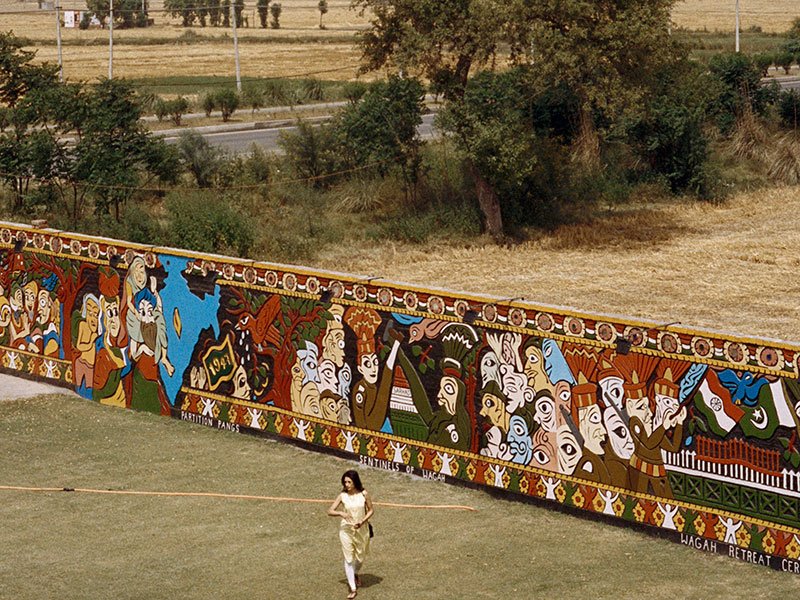

|

| Guards on the Pakistani side of the Wagah border. Photo: Michael Turek |

The beating retreat ceremony at Wagah is hyper-choreographed nationalism. Pakistanis sit on this side, Indians on that. The gates between the two countries are closed, so the only awareness you have of each other is ear-splitting, migraine-inducing sound. Who can play their music the loudest? Can your military announcers outscream theirs? (It all sounds to me like they’re saying ‘eeeeee-unnn’, but after consulting at least four people, I conclude that it might be “Attention”.) Before the ceremony begins, a man with one leg twirls on the empty runway, unsmiling. He holds a large Pakistani flag in his hand and hops wildly to the music. He seems symbolic of Pakistan, broken, caught in a maddening trance. But an Indian friend tells me later, when I show him a video of the man, that I’m wrong. It’s not delusion, it’s love and devotion.

The soldiers march in a Basil Fawlty walk, legs akimbo, flexing their muscles. The Pakistanis walk to the Indian guards as the gates creak open, and the Indians walk to their Pakistani counterparts. For the next half hour, they stomp towards each other and then away, the announcer growling on the microphone, “Eeeeeee-unnn”. I keep wondering what I’m missing. I don’t want to cheer like the crowds, I don’t want to celebrate macho hostility between these two countries, huffing and glaring at each other across a narrow strip of land they call a border. Right on the threshold between the two countries, a negligible strip of no man’s land, two guards in different shades of khaki camouflage (India in beige, Pakistan in black), cradling modern-looking machine guns in their arms, are standing so close they could kiss. Like with the others, though, it’s the weapons, not the proximity, that you notice.

But then I realise it’s an act. As our respective border guards stomp towards their flags and prepare to unfurl them, there is a second—a mere glance—when the Pakistani soldier looks at the Indian and winks.

The Indian soldier, the smallest hint of a smile on his lips, nods and winks back. On cue, they lower the flags. They are complicit, sharing a secret we’re not supposed to notice: this is a coordinated effort, and both sides know that they’re playing, while the rest of us sit in the stands, trying to peek through a gate at the other side.

Crossing the border

|

| Wheat fields on the Indian side of the border. Photo: Michael Turek |

I struggle to connect Lahore to the things I know. How it looks like Delhi, a comparison I shape out of memory. How it’s different from Karachi, moulded from instinct. But I have never been to Amritsar before, and though I have travelled from Pakistan to India countless times—on book tours, for talks, to see old friends—I have always flown. Nothing prepares me for what I will feel crossing the border by foot.

As I reach the first Wagah checkpoint, I see an old farmer in the nearby wheat fields, his white salwar-kameez standing out in the sea of gold. Just beyond him, steps away, are floodlights. “That is India,” my driver informs me.

Immediately, there is a palpable tension on the Pakistani side, all nerves and rush. Hurry up, where are your papers, only passport-holders. There are only three other people crossing immigration at the time, but you would think there were a hundred. Amid the twitchiness, though, there are still small markers of humour. Over all the immigration officers’ desks is a printout that reads, in red font, “We respect all. We suspect all.” And despite all the anxiety, there is no delay and I walk quietly across to the other side. An Indian border guard smiles after checking my passport and points to the painting of Mahatma Gandhi on the gate demarcating India from Pakistan. “Photo with Bapu?” he asks. I board a bus that will take me to Indian immigration, and I notice, smiling down from a large billboard, another Indian icon: Virat Kohli.

If Pakistan’s immigration feels anxious, India’s feels deeply relaxed. Oh, immigration? You want to cross the border? What, today? The lights are not switched on in a part of the building, and aside from administering me polio drops—required for entry, even though I was revaccinated a year ago—everything moves at a sleepy pace. The bags sit, marinating, in the X-ray machine, and papers are slowly unfolded, checked, refolded. There is waiting and then hanging around and then more waiting. And then we are out.

If you walked between Pakistan and India, it would take you three minutes. But because of this, because of borders and nation states, it takes an hour. As I come out of Attari, the same wheat fields all around me, the earth the same shades of gold and green, and the same smell of the sun burning against the dust make me feel I haven’t moved. Lahore isn’t like Amritsar. It is Amritsar. Punjab is Punjab, no matter what side of the border you stand on.

Amritsar and the psychological border

|

| Frescoes in the temple at Pul Kanjri. Photo: Michael Turek |

Driving past Pul Kanjri, where Shah Jahan built canals to carry water to the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, I understand why Cyril Radcliffe, the lawyer called in to partition India, reportedly went mad. How do you divide a soul?

Everything here is a reminder of the other side. The seasons, the crop, the sowing and the reaping done in tandem across those floodlights that demarcate a border. Everywhere you can hear the wind rustling through the fields of wheat, like music.

Amritsar is proud and beautiful. All over the city are landmarks to the struggle its people played in the freedom movement. Here is Jallianwala Bagh, preserved with bullet marks and battle scars of the thousands of innocents who died when General Dyer ordered his troops to fire 1,650 rounds of ammunition on unarmed civilians. There is a statue, garlanded with marigolds, of Shaheed Udham Singh, who killed General Dyer in London many years later. In a small lane, near Kesar Da Dhaba, where I eat kulchas and drink Limca, I see a small altar to Jhoole Lal, the Sufi saint revered among both Hindus and Muslims in Pakistan. Above him are Krishna and Durga. This is the symmetry of South Asian history. This was the beauty of pre-Partition India—that it had the capacity and the heart to absorb everything and everyone.

At every point in Amritsar, walking through Pakistani Bazaar (where a lady randomly stops me to confirm whether the fabric she’s looking at really is from Lahore), sitting in the quiet of Khair-ud-Din Masjid at dusk, or drinking thick, creamy lassi at a small stall, I see Lahore.

I am not sentimental, but as the hours go by, no one believes me. With great flourish, breakfast is presented as being a special Amritsari treat: a taut, crisp poori. “But we eat this in Lahore too,” I mumble, spooning some chickpeas into a poori pocket. Another offer after lunch: “Would you like to try the jalebi? They’re fried extra thin and soaked in sugar syrup.” “That’s how they eat them in Lahore too,” I say in a small voice, embarrassed at a refrain now becoming predictable and familiar. “How about phirni? Sweet and milky, with scrapings of silver foil on top?” The same, I promise, the absolute same.

When we pause by a dhaba for a cup of chai and watch the swirling leaves, poured high up from one steel pot to another, sugar thrown in by the palmful, foam sprinkled with slivered almonds and steam that smells of cardamom, I tell Michael, the photographer, that Lahore drinks its tea like this too, just like this. I am not sentimental, I swear, the tea burning my tongue. I wish for a moment that he had photographed this very scene in Lahore. I think back to Lahore and wonder why we didn’t have tea there, just so everyone would know this small, burning fact like I do.

If one of the excitements of travel is difference—knowing that there are places in the world where the food is not what you eat every morning, the music is alien to your ears, the people are unknowable, unlike you and all that you have come to know and believe—then what do I call this? After dinner, we stand at a roadside stall for meetha paan. Men get off motorcycles as we wait and buy single cigarettes. Just like home, I say quietly to myself.

Looking back now, Wagah seems unreal—a Disneyland of performed differences, a psychological border more than anything else.

The Golden Temple

At 3.30am, when the sky is still dark, I visit the Golden Temple. Harmandir Sahib, they call it. Everyone’s temple. The foundation stone of Sikhism’s most holy site was laid by Hazrat Mian Mir, a Sufi saint, who had been invited by Guru Arjun from Lahore especially for this. Symmetry, again. A reminder of a country that once belonged to everyone, before it was partitioned.

The temple is quiet, except for the sounds of the kirtan being sung. It is breathtaking; the calm, the beauty, the solitude. As I walk around the sarovar, or sacred pool, I am told the water is sourced from River Ravi. This is the core of Sikhism, how open it is to other faiths, how much it includes and considers its own. After the Palki Sahib is carried from the Akal Takht to the Harmandir Sahib, the holy Guru Granth Sahib awakened with dawn’s first light, I wonder if the temple will transform. If it will become busier, louder, feel more chaotic. But it doesn’t. It just somehow continues to thrum with the same peaceful energy, its people serenely meditating and praying at all points along the compound.

One not without the other

|

| Sarhad, a restaurant near Wagah on the Indian side. Photo: Michael Turek |

There is symmetry everywhere between Lahore and Amritsar. But there is also loss. Without both cities, Punjab is an incomplete story. How do you honour the Golden Temple without Nankana Sahib? Who can tell Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s story of conquest and empire from only one city when his imprint is historically and emotionally on both? The truth is that you can’t. Amritsar without Lahore is but a fragment of Punjab’s history. And Lahore without Amritsar is only half felt. The same is true for India and Pakistan, especially for its people.

My journey across the border between these twin cities is not bittersweet, as I thought it might be. It is sad and dark, a constant reminder of the absence and the presence of one people rendered in half. Just like someone who’s lost a limb still has a memory of it being attached and feels pain, so do we. They say phantom limb pain lessens with time. But all these decades later, walking through Lahore and Amritsar, I felt pangs all the time.

It’s not enough to visit the Wagah border and just watch the ceremony as hundreds do every day on both sides. Forget the ceremony, cross the border. That’s where the most beautiful, and true, journey resides.

Getting there: Drive from Amritsar to Lahore through the Wagah border, open from 10am to 4pm every day. Or fly to Lahore with Pakistan International Airlines from New Delhi. Indian passport-holders can apply for a Pakistani visa at the High Commission of Pakistan in New Delhi. Visas take three working days to process and cost `120.

--------------

AMRITSAR

Where to stay

1) Hyatt Amritsar: The city’s best five-star hotel has luxurious rooms with great views. (Doubles from `4,600)

2) Ranjit’s SVAASA: The converted haveli has an interesting curio shop. (Doubles from `4,500)

Where to eat

1) Kanha Sweets: There’s only one thing on the menu: crisp pooris accompanied by Amritsari chhole and aloo.(Shop 1, Lawrence Road)

2) Kesar Da Dhaba: The Punjabi dhaba serves legendary parathas and lassi.

3) Makhan Fish & Chicken Corner: Home to the famous Amritsari fish, it serves standard Punjabi fare.

4) ThaiChi: Hyatt Amritsar’s pan-Asian restaurant is a great fine-dining option.

5) Sarhad: This restaurant serving North Indian cuisine uses architectural details from monuments in both countries.

Where to shop

1) Raunak Punjabi Jutti: Choose from a huge selection of traditional Punjabi footwear in all colours and patterns.(Hall Gate, Pink Plaza, Katra Ahluwalia)

2) Singh Sarees & Suits: For traditional phulkari dupattas and other ethnic wear. (Katra Jaimal Singh)

What to do

1) Harmandir Sahib: The Golden Temple is visited by devotees from all faiths and countries. (Golden Temple Road)

2) Pul Kanjri: Once a major trade centre, it is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. (On the Amritsar—Lahore road, near Dhanoa Kalan village)

3) Khair-ud-Din Masjid: Hear the azaan, as the sun sets, at this beautiful 19th-century mosque. (Hall Bazaar)

4) Wagah border ceremony: Witness the daily military performance by the forces of India and Pakistan. (Wagah village)

LAHORE

Where to stay

1) Avari Lahore: The five-star hotel has great food, from Japanese to Mughlai. (Doubles from PKR22,000 or ?13,400)

2) Pearl Continental Hotel: The city’s most luxurious hotel. (Doubles from PKR34,000 or `21,200)

Where to eat

1) Haveli Restaurant: Enjoy delicious kebabs with a view of the Badshahi Mosque.

2) Fujiyama: At the Avari hotel, it serves the city’s best sushi and has live teppanyaki counters.

Where to shop

1) Liberty Market: Browse through Dupatta Gali, Khussa Mahal and the shawl stores. (Noor Jahan Road)

2) Khaadi: Contemporary apparel for women and children, as well as home linen.

3) The PinkTree: For beautiful tunics in pretty pastels and warm hues.

What to do

1) Badshahi Mosque: The city’s most famous mosque is a perfect example of Mughal architecture.

2) Lahore Fort: Built during the rule of Mughal Emperor Akbar, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

3) Lahore Museum: Check out the exhibits on the subcontinent’s major religions and on the freedom struggle.