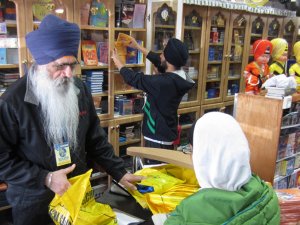

It’s just about 550 years ago that Guru Nanak appeared. He trod the earth and founded a movement – a way of life – that we now treasure and honor as Sikhi or Sikhism. Over 25 million Sikhs and their friends worldwide are abuzz with celebrations. They capture our hearts and minds like nothing else as the coming days and weeks will continue to inspire us.

There were two religions extant at that time in the Indian Subcontinent – Islam and Hinduism. Muslims were a minority but were the politically dominant power, the rulers. Hindus were the majority by a magnitude but as subjects little better than slaves. The two faiths were totally at loggerheads with each other. Muslims were bent on converting the Hindus. Hindus were equally adamant and wanted to live by their own traditional caste-driven realities and remained largely resistant to reformation of societal problems that had emerged over time.

History and tradition tell us that Nanak’s message was uniquely inclusive of the two rich but antagonistic faiths. In many ways his vision brought the two to common ground. The Sikh scripture, Guru Granth, contains the writings not only of the Sikh Founder-Gurus but also Muslim and Hindu saints of the time. This was necessary if the three — Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs — were to live together as neighbors in the same land, keeping in mind Guru Nanak’s teachings that, regardless of our religious labels, we are all children of the same Infinite Creator.

History also tells us that both Hindus and Muslims were deeply attracted to Nanak’s universal message. The irrefutable proof of this assertion is the fact that when Guru Nanak shed his mortal coil at Kartarpur, the commune that he built on the bank of the River Ravi, a serious conflict broke his followers apart and shattered the peace between them. His Muslim followers wanted to bury him as per Muslim rites while his Hindu disciples wanted to cremate him according to Hindu traditions.

Tradition tells us that when they pulled back the cover on Nanak’s bier, the body had disappeared; only some flowers remained. And then humans did as humans will. They angrily divided the flowers and tore into two halves the cloth that had covered Guru Nanak’s body. Muslim followers of Guru Nanak did to their half of the sheet what Muslim rites dictated, his Hindu followers cremated their half a la Hindu rites. On one bank of the river Ravi Muslims built their memorial to Nanak, across the river on the other bank Hindus built their own marker.

Soon enough, history tells us the river Ravi flooded and forever washed both memorials away to oblivion.

Now that, in my view, is divine justice.

But where are we today, nearly 500 years later? What realities stare at us today? What happened in the half a millennium? Open corridors with closed minds would never be the solution. Life offers some enduring lessons.

Centuries of religious tensions, wars and bloodshed followed. Sikhi does not believe in proselytizing or converting others. Let them make own choices; the Sikh way is open to all who come. Sikhi is a peaceful way of life. Sikhs are non-violent but never passive; they had to take up arms in self-defense, and they accumulated an unparalleled record of sacrifice and martyrdom in the cause of justice and human rights for all, regardless of their religious label. Islamic presence in India had become known for forced conversions. When the British left India in 1947, the country was divided based on religion into a nominally secular India and a Muslim Pakistan. The partition of the country followed some of the bloodiest rioting and killings of civilians that the world has ever seen.

Now, free India has newly spawned a muscular movement -- Hindutva -- that seems bent upon redefining India’s secular principles and credentials into a defiantly Hindu identity to the detriment of its many visible and vibrant minorities. Should we not fittingly label this as personification and abject proof of vilification and diminishing of others, if not hatred? The resulting nations – India and Pakistan that have fought many wars to the detriment of each other, both neighboring countries and nuclear powers, mutually hostile forever?

On a lighter note I am reminded of some contemporary American humor. Years ago, a very close friend said to me “I love you to pieces.” And, on one of my darker days, tongue in cheek, I couldn’t resist the tasteless rejoinder: “Thank you, but I am not quite ready to celebrate my pieces yet.”

Certainly, we Sikhs revere Guru Nanak and would willingly die to defend his message – history is witness to that. But in many ways, don’t we often think that Guru Nanak’s universal vision for the people deserves to be rediscovered? That would be the most appropriate celebration.

For what time has done to Guru Nanak’s timeless message, sometimes I wonder: If this be love, pray tell me, what then is hate?

By I.J. Singh & Neena I. Singh (2018)