I have often spoken about Guru Gobind Singh as a man without parallel. Many Sikhs take umbrage at that. The Guru was divine, they insist, not mortal. But in his lifetime, his own Sikhs honored him as Mard Agamra, meaning a peerless man.

Most religions have one Founder-Prophet who teaches a way of life. The tenets of the faith are elaborated during his life-time.

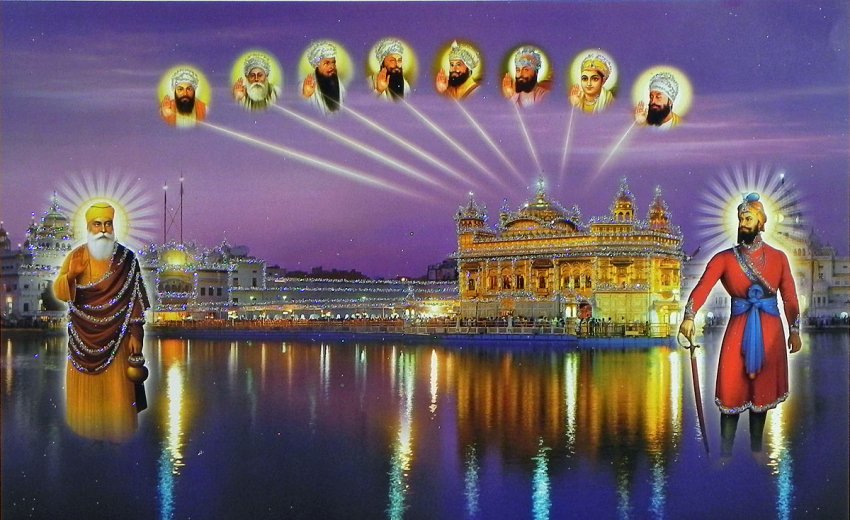

Sikhi is a rare example of a faith with more than one Founder-Prophet. So, my tribute will focus less on Guru Gobind Singh as a lone knight whose earthly journey finished at the young age of 42, but more as an integral part of ten Gurus working in tandem towards a common goal.

The Gurus faced a multi-task agenda of remaking society. This demanded sustained and deft mentoring for over two centuries.

1. India in the 15th to 17th Centuries

Punjab, where Sikhi began commands a special place in India. Khyber Pass connecting Afghanistan to northwest Punjab was the most widely used corridor leading into the Indian Subcontinent. For centuries, it was the trade route and the preferred pathway for countless invaders into India.

This Subcontinent was a jigsaw puzzle of many quasi-independent nation-states, mostly at logger heads with each other. This made India an easy target for conquerors, where many invaders with embarrassingly small forces, easily prevailed because of rivalries between local satraps who were readily co-opted and corrupted.

Two populations dominated India then. Muslims, though a minority, held all political power. Hindus, vastly larger in number, but riven by a rigid vertically stratified caste system, survived under repressive laws and extreme State tyranny to convert to Islam willingly or at the point of a sword.

Into this reality strode Guru Nanak, the Founder of Sikhi.

2. What do a people need?

How do a people under virtual siege reclaim their dignity? This becomes the mission statement of Sikhi.

Goals seemed akin to the not so simple art of nation building. A nation with open borders, not arbitrary lines drawn in the sand, not defined by geography, currency, or religion. Instead, a defining ideology, philosophy, and core of common ethics. Add economic hope, self-governance, freedom of expression, a model of conflict resolution and justice.

In brief, a system that is accountable, transparent, representative, and dedicated to the public good. Sikhi was their agent for transformational change -- a “human development movement.”

3. Sikh Building Blocks for National Development

Let’s note some milestones in the path of Sikhi from Guru Nanak to Guru Gobind Singh that contributed to an increased social capital of the community:

Guru Nanak interacted with many of the scholars of the day. He created the Sikh model of Utopia at Kartarpur, starting with pangat and langar, emphasizing lessons in sharing together, service to the needy, irrespective of caste, clan, or economic status. He taught moral and spiritual precepts of a productive life, including frank teachings against the unequal place of women in Indian society. Guru Nanak created the glue that binds a community.

Subsequent Gurus continued the path. By the time of Guru Gobind Singh, they had established at least 12 townships from Khadur Sahib to Amritsar, Anandpur and Damdama.

A “national convention” of Sikhs was slated twice a year on Divali and Vaisakhi. Akal Takht was established. The Gurus bequeathed to us an egalitarian, progressive structural model of accountability, self-governance, and transparency. The results were self-evident during the misl period and the time of Ranjit Singh’s rule of greater Punjab.

The standardization of the norma loquendi, language of the people -- Punjabi, the language, Gurmukhi its script. Centers for the propagation of Sikhi in Punjab and beyond; many center-heads were women. Widows were encouraged to remarry, the practice of sutee was prohibited.

Guru Arjan collated the writings of his predecessor Gurus, and some Hindu and Muslim Bhagats, in the first recension (Adi Granth) of the Sikh scripture in 1604.

Guru Hargobind raised an army, as did every Guru that came after him, and elaborated the seminal Meeri-Peeri doctrine. It asks that our inner life and outer existence -- the worldly and the spiritual core -- be in sync, never in conflict.

During Guru Tegh Bahadur’s tenure, State repression of Hindus became extreme. He argued their case. At his refusal to accept conversion to Islam he was publicly beheaded. His martyrdom was for freedom of religion, regardless of its label.

In accepting martyrdom, the teachers, Guru Arjan and Guru Tegh Bahadur, taught how to live and die with dignity.

Thus, systematically, the civic infrastructure of Punjab, its economic muscle and community cohesion were developed. Nation building depends on such transgenerational evolutionary processes towards revolutionary goals.

Mine is a thumbnail notation of mind-blowing events that took more than two centuries.

4. Legacy of Guru Gobind Singh

Successful human movements rest on two structures: developmental initiatives, and periods of consolidation. Both phases progressed apace throughout the Guru period and the short eventful life of Guru Gobind Singh. His mission was critical to Sikh identity and to formalization of institutions that, thanks to the earlier Gurus, existed in nascent form.

With Guru Gobind Singh rested the pivotal responsibility of coalescing and melding them into a grand design for lasting purpose. I point to some inter-related themes that define the many splendored reality of Sikhi today.

The Meeri-Peeri doctrine elaborated by Guru Hargobind flowered under Guru Gobind Singh. From this arises the holistic primal idea of Sikh being a Saint-Soldier in life.

Guru Gobind Singh formulated four transformational events/precepts: 1. The rite of Amrit – a defining marker of Sikh identity; 2. As a free people Sikhs keep arms and are prepared to defend freedom; 3. The Guru Granth Sahib henceforth to be the repository of Sikh spiritual heritage; 4. Temporal authority to reside in the Sikh Panth acting in awareness of the spiritual primacy of Guru Granth.

It follows from this that there was to be an end to the line of Gurus in human form.

Guru Gobind Singh staged the defining event of Amrit Sanchar in 1699; five Sikhs answered his call for a head, and were the first to be initiated into the Khalsa Order. Then, in a classic role reversal, they transformed Guru Gobind Rai into Guru Gobind Singh. The Guru prescribed five articles of faith, and mandated rejection of the reprehensible caste system.

From this modest beginning Guru Gobind Singh led the Sikh nation that now is a significant presence in the world.

War had been thrust on Sikhs. What were the terms of engagement? What ends justify armed insurrection? What’s a just war and what is not? Guru Gobind Singh clarified these issues by his conduct and in his composition, the Zafarnama.

War is not for pillaging, seizing people, or territory. Weapons are drawn only when all other means fail. Negotiations for peace continue even during war. Weapons are laid down whenever the foe appears so attuned. The enemy who surrenders or is captured is to be treated honorably. Finally, to be humble in victory, graceful in defeat.

Without the five articles of faith Sikhi would have been rapidly swallowed into the all-embracing tent of varied practices that define Hinduism. I buttress my argument with case studies of Buddhism, and Jainism. Both Indic religions are doctrinally distinct from Hinduism, yet their identity has been largely subsumed within Hinduism; neither retains much of an independent existence. Buddhism was at one time a powerhouse in numbers within India but no longer, though it remains a growing presence outside India.

Factions in resurgent Hinduism now seem hell-bent on redefining Sikhi as a reform wing of Hinduism; only the independent Sikh practices and distinct identity continue to stand in the way.

The gurdwara remains a platform for Sikhs to discuss their needs and community life. The Sarbat Khalsa, a representative model of Sikhs worldwide, is a lineal descendant of the conclaves that date from Guru Amardas. It ensures that Sikhs worldwide can have a voice in designing policy, such as the need to finalize a Sikh Code of Conduct during mid-20th century. The takhts exist, with the Akaal Takht as historically supreme, as possible models for conflict resolution.

During Guru Gobind Singh’s tenure much of the infrastructure of an emerging community was in place for representative administrative structures, mostly as prototypes with built-in self-correcting servo-mechanisms. The operative word here is “prototypes.” Many seem dysfunctional today.

With minor additions to the Adi Granth, Guru Gobind Singh finalized the Guru Granth. It contains very little history and is not prescriptive. It provides an ethical framework but not a sin quotient or a catalogue of Do’s and Don’ts; the onus is ours to navigate the path and make a life. Thus, the Guru Granth remains free of ethno-centric, cultural, geographic, and historically time-bound constraints. It remains a universal and timeless guide to shape a life.

Keep in mind that the action points noted today were not isolated programs but well thought out steps towards a long-term purpose.

The end result was shaped by Guru Gobind Singh

History notes that the post-Guru period was marked by Sikh ascendancy. The Khyber Pass was closed to the yearly invasions and an enlightened Sikh kingdom established in the greater Punjab that lasted until the advent of the British almost fifty years later. That time also saw the first land reform policies in India.

Guru Gobind Singh saw that his Sikhs, had come a long way on Guru Nanak’s path, and now deserved the responsibility of self-governance. When he asked the first five Khalsa to initiate him he joined his Sikhs as one of the people, subject to the same rules – aapay gur chela. He pointedly attributed all his achievements to his Sikhs (Inhi kee kripa kay sajay hum haen, naheen mo so garib krore paray Gyan Prabodh in Dasam Granth.) This speaks of the modern idea of Servant-Leader, that finds resonance in modern models of academia and management.

Most people, including Sikhs, opt for one of two choices when they weigh the legacy of Guru Gobind Singh. Some see his contributions as independently transformative but disconnected from the Sikhi of Guru Nanak; thus, they miss their collective impact. Or else, they view Guru Gobind Singh as sharply departing from the peaceful path of Guru Nanak. Either way the continuing coherence of the Sikh way from Guru Nanak to Guru Gobind Singh is lost.

I ask you to reject such binary choices. Every action of Guru Gobind Singh is rooted in the life and teachings of his nine predecessor Gurus. Guru Gobind Singh’s life and work embody the final integrative chapter on the development of the Sikh message. He was the master-weaver on the complex tapestry that is Sikhi today.

Such a massive transformative remake of society can neither result from a law or two nor accomplished in a generation or two. Paradigm shifts do not occur in a vacuum. Hence the long eventful path from Guru Nanak to Guru Gobind Singh.

Isn’t this a captivating multi-generational saga of a revolution via evolution that created a whole that’s greater than the sum of the parts?

5. An After-Thought

Guru Gobind Singh, as a man of the people, a leader extraordinaire, a farsighted administrator, community organizer and as tactician, strategist and general in war and peace, remains unparalleled.

His actions imply that he found his Sikhs to be on the path of maturity and wished them to go forward with wisdom and determination.

Have we enhanced or diminished our legacy? As we re-fashion it to the realities of a different world, how do we remain true to the fundamentals.

Where are we on the path, how exactly we got there, and what course correction is called for are matters on our plate.

A question remains: Did Guru Gobind Singh overestimate us and what shall we do with the mess of pottage that we have created?