Growing up in India I never lived in Delhi or Mumbai (nee Bombay) and my visits to the two major Indian cities were few and brief. I never developed much of a sense of either town.

Over the years, when people asked about my impressions of Delhi or Bombay my dismissive response was that Bombay was a plastic town — a celluloid reality, like Las Vegas or Los Angeles — while Delhi had a sense of history, like New York. I don’t really know where I came by this sound bite but it sounded good so I used it often.

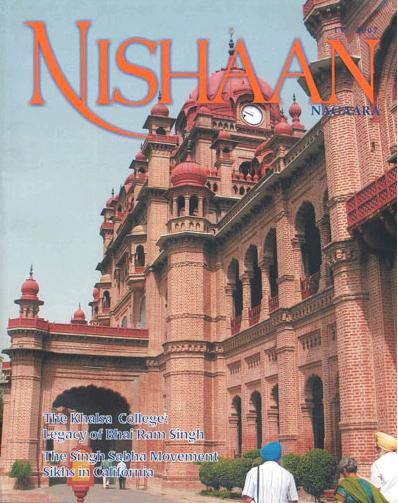

Then last year Nishaan,

the colorful Sikh quarterly from Delhi, asked me to trace the Sikh (and

Punjabi) presence in Delhi. Pushpinder

Singh Chopra, Bhayee Sikander Singh Bagriyan and Monica Arora provided much of

the research material. The more I

learned about Delhi, the more I became entranced with it.

Then last year Nishaan,

the colorful Sikh quarterly from Delhi, asked me to trace the Sikh (and

Punjabi) presence in Delhi. Pushpinder

Singh Chopra, Bhayee Sikander Singh Bagriyan and Monica Arora provided much of

the research material. The more I

learned about Delhi, the more I became entranced with it.

And Nishaan published the essay as the Editorial for its December 2011 issue that was dedicated to the story of Delhi.

Today I offer you a slightly modified version of that editorial.

Ever since Guru Nanak trod this earth and Sikhi arose, Sikhs have been a glowing and important presence in Delhi, Old and New. Of course, as in all life, the good and the bad intermix. The focus today is on New Delhi, but the city’s roots lie in the old town and that connection cannot be sundered; it must be reconciled in any narrative. Old Delhi and its new adjunct are truly inseparable.

I look out the window in my home town, New York; some parts are almost 300 years old with narrow, winding streets; others are new high rises, kissing the sky. Similarly, it’s hard to draw lines between the old and the new in Delhi; there are layers to its narrative.

Just a few hours in Delhi is enough to see that the heartbeat of Delhi is synchronous with that of Punjab. In fact in many ways, Delhi appears to be another, if bustling and progressive, extension of Punjab. That some other states of India are wedged around and between Delhi and Punjab becomes apparent only when one looks at a map of the country or encounters border crossings in traveling between Delhi and Punjab. A common culture continues to unite the two.

It takes a little parsing of history to feel the intimate connection, akin to an umbilical cord, that joins them. Despite the passage of time, this cord remains anatomically and functionally viable. The vitality of the capital city of Delhi has always stemmed from this structural and functional intimacy with Punjab and Punjabis, as much now as ever.

The land that is now Delhi has occupied both mythologists and historians for centuries. This is testimony of its importance to both the people of India, even before there was an ‘India,’ as well as to Indians today, and speaks to its defining place in the nation that now is the Republic of India.

Indian myth and lore traces the antecedents of Delhi to the times following the Mahabharata. During that intersection of fact and myth, Delhi was perhaps the city of Indraprastha. Nothing remains of it now except the legend. The earliest record of that era comes from the 12th century when its last Hindu ruler, Prithviraj Chauhan, held sway.

Qutb-al-din Aibek defeated Prithviraj, and renamed the township as Delhi. It became the seat of his government. Over the centuries, hordes from the north and northwest including the Mongols, continued their periodic invasions through the Khyber Pass into Punjab and then on to Delhi. There have been many incarnations of Delhi.

In the thirteenth century, Ala-ud-Din Khilji built a new fortified city (Siri) as Delhi’s first rebirth at its south. Less than a century later, Tughlak rulers founded a new city, Fatehpur-Sikri on the Delhi-Agra road but it had to be abandoned because of scarcity of water. Later, his successor established another city, Firozabad as the new capital which is now embedded in Old Delhi.

Delhi has had many more lives than the proverbial cat. Invasions continued and Delhi died a thousand deaths, with just as many reincarnations. In the sixteenth century, Mughal emperors temporarily shifted the capital of their far flung empire away from Delhi, but the romance and lure of Delhi prevailed and that’s where they returned.

But for reasons that remain unexplained and untraced, the Sikh influence on Delhi, Old and New, remained relatively unexplored by historians. Then in the December 2011 issue of the Nishaan, Scholars and historians explore the Sikh stamp on Delhi.

As the Sikhs gained strength in Punjab, Mughal political power, inimical to the larger populace remained concentrated in Delhi and thus connection and confrontation between the two was inevitable.

At least two places commemorate visits by Guru Nanak to Delhi. Guru Angad did not visit Delhi but the Mughal Emperor Humayun, after his defeat, visited the Guru on his way into exile from Delhi.

Bhai Gurdas, in his eleventh Vaar, mentions the presence of Sikhs in many cities across the land, including Delhi. They lived freely and openly. At that time, tensions had not yet escalated to open war between Sikhs and the Mughal rulers, even though Guru Arjan had been martyred and Guru Hargobind had fought four battles with the ruling empire. Remember that these were pre-Khalsa times.

Guru Har Rai did not visit Delhi, but the rebel prince Dara Shikoh visited the Guru while fleeing from the army of his brother, Aurungzib, who overcame his father and siblings and captured the throne of Delhi. This new emperor questioned some lines in the Adi Granth. Guru Har Rai deputed his son, Ram Rai, to go to Delhi to assuage Aurungzib’s concerns. Ram Rai unfortunately deliberately misread Gurbani to the emperor’s satisfaction but suffered the Guru’s wrath

Guru Harkishan visited Delhi, but refused to meet the emperor. Guru Tegh Bahadur visited Delhi several times, finally to uphold the cause of the Kashmiri Pandits against brutal oppression for which he was martyred. He was beheaded in what is now Chandni Chowk of Old Delhi on 11 November, 1675.

The palace associated with Gurus Hargobind, Harkishan, and Tegh Bahadur is now Bangla Sahib. Gurduara Sees Ganj stands at the spot where Guru Tegh Bahadur was martyred. Gurduara Rakabganj is where Lakhi Rai Vanjaara surreptitiously brought and cremated the body of Guru Tegh Bahadur. In 1707 Guru Gobind Singh personally marked the spot at Rakabganj. Two centuries later, the British selected the same site to build India’s new capital.

In the post-Guru period, Mata Sundri, the wife of Guru Gobind Singh, lived in Delhi until her passing in 1743. But, as is usual with Indian history, the narrative seems largely incomplete. During that period, the Sikhs fought many battles with the Mughals. In Punjab, Banda Singh Bahadur had wrecked the Mughal presence and shaken the rulers of Delhi. Were the Mughals not aware of her presence? How was she able to survive in the center of enemy territory?

Banda Singh Bahadur’s public execution in Mehrauli, south Delhi is another milestone in the history of Sikhs in and around Delhi and it is a compelling saga. By then, Mughal power was fatally weakened and Sikhs were in the ascendance. In 1765, under the command of Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, Sikhs defeated the rulers of Delhi even though skirmishes and battles continued. In 1783, the Sikhs led by Baghel Singh, laid a siege which lasted two months. Their base, where close to 30,000 troops were encamped (Tees Hazari) is now the site of the Delhi Courts.

Sikh warriors prevailed. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, Jassa Singh Ramgharia and Baghel Singh flew the Nishaan Sahib from the ramparts of the historic Red Fort. This is exactly the same location from where the Indian Prime Minister today addresses the nation every year on India’s Independence Day. It was also in New Delhi that the Sikhs, elected to India’s first free parliament, chose not to affirm the Indian Constitution because parts of this rankled then — and the same parts continue to offend Sikhs today.

I have presented a synopsis, admittedly swift and brief, of the Sikh presence in Old Delhi. But our attention now turns to New Delhi. In 1911 the British announced shifting of their Indian Empire’s capital from Calcutta to Delhi. Swinburne, Lutyens and Baker were commissioned to design a modern Delhi. Rai Sina, Rakabganj, Malcha, Madhoganj and Jaisinghpora were key villages where New Delhi stands today.

The British designed a lodge (now the Presidential Palace) for their Viceroy to rival the Red Fort which was pride of the Mughal rulers. Then they wanted to build a wide tree-lined boulevard that went through Rakabganj. Lutyens, unaware of this gurduara’s historical significance, ordered dismantling of its walls. Malcolm Hailey, an indologist sympathetic to Sikhs, advised against it, but was ignored. The wall was demolished in 1913, leading to massive protests. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar flamed further anger in the Sikhs. The British sought Sikh support in the First World War; and at the close of the war, in 1921,the walls of Rakabganj as well as the seized land were restored to the Sikhs.

The city of New Delhi was officially inaugurated in 1931. The Delhi Gurdwara Management Committee came into existence in 1974 to manage gurduaras in Delhi, Old and New.

The

design of New Delhi may have come from Lutyens and associates, but the world-class

and first-rate construction is a product of mostly Sikh engineers, contractors

and builders. Almost all were recognized

by the British government with awards but three were also knighted, including

Sir Sobha Singh, father of the eminent writer Khushwant Singh. The most prominent of them were collectively known

as the Punj Pyaray.

The

design of New Delhi may have come from Lutyens and associates, but the world-class

and first-rate construction is a product of mostly Sikh engineers, contractors

and builders. Almost all were recognized

by the British government with awards but three were also knighted, including

Sir Sobha Singh, father of the eminent writer Khushwant Singh. The most prominent of them were collectively known

as the Punj Pyaray.

Among these lamplighters were Sardars Baisakha Singh, Dharam Singh Sethi, Teja Singh Malik, Narain Singh and Mohan Singh.

Following the partition of India in 1947 and the expansion of New Delhi, came many new Sikh builders; the most prominent amongst these being Uttam Singh Dugal from Rawalpindi and his son Harcharan Singh; the names of Lachman Singh Gill and Mohan Singh (who also introduced Coca Cola into India) must also be recorded.

Of the most influential Sikh authors, writing on Sikh causes, I would add two eminent scions of the builders of New Delhi -- Khushwant Singh, son of Sir Sobha Singh and the late Patwant Singh. And today, reminding us of both the Jassa Singhs and Baghel Singhs, we have the eminent economist Manmohan Singh who sits astride the Indian nation as the Prime Minister of India and General Bikram Singh, the chief of India’s vast army – the third largest in the world.

Manmohan Singh is a world-class economist and the first Sikh prime minister of India. General Bikram Singh is only the second Sikh in his high office as Indian Army Chief; this in spite of the fact that the cadre of senior officers and generals in the Indian army has always had a preponderance of Sikhs. In the early 1950s, more than 50% of senior generals were Sikhs but were systematically sidelined. Two Sikhs, Arjan Singh and Dilbagh Singh, became Chiefs of the Indian Air Force but another two who were logically in line, were retired on the eve of their taking over.

The story of Sikhs and New Delhi would be woefully incomplete without a brief comment on the mass murders of thousands of Sikhs in November 1984 in a pogrom directed by people with political power. That is when Khushwant Singh returned his honors to the government and drew a wrenching parallel between the lot of Sikhs in India and that of Jews in Nazi Germany during the Second World War. Sikhs rightly remember the killings as a holocaust and attempted genocide.

During the troubled decade of the 1980s, at the height of a tense exchange on the killings of Sikhs in Delhi, one visitor to New York – a representative of the ruling political faction (Congress Party) from India baited Sikhs with the tasteless challenge: “Your Sikh kingdom was based in Lahore; why don’t you all go to Pakistan and capture Lahore?” I could not resist perhaps an equally tasteless response, “Why don’t we take Delhi now, as the Sikh Nishaan Sahib also flew there at one time; Lahore can come by and by.”

Until the British and the French came to India by sea, most invaders entered India through its northwest corner and hurtled into Punjab to stay, conquer and plunder, return or perish in defeat. Consequently, Punjab has known little peace except briefly during the reign of Akbar during the 16th century or for another half a century in the 19th during Ranjit Singh’s consolidation of power.

It has been rightly said that we Sikhs make history but we do not record it. Perhaps there was little time or leisure to do so. But our early history when added to the 500 years of Sikh presence in Punjab have embedded and encoded that lifestyle in our DNA.

In its December 2011 issue, Nishaan captured some of those voices (such as that of the writer Khushwant Singh) that we can still access, along with existing records so that they are not lost in time. I know that my piece here paints a larger-than-life canvas with broad brush-strokes. But readers will find details aplenty in the historical record as well as in Nishaan with striking images that enshrine its history forever.

Still there are dots that I did not connect and nuggets of history that I missed, including the fact that apart from the ten historic gurdwaras there are scores more, ever vibrant and attracting both adherents to the faith and millions of others who visit Delhi, the capital of India and one of the great cities of the world.

Readers are invited to move the story forward.

October 19, 2012