Book Review

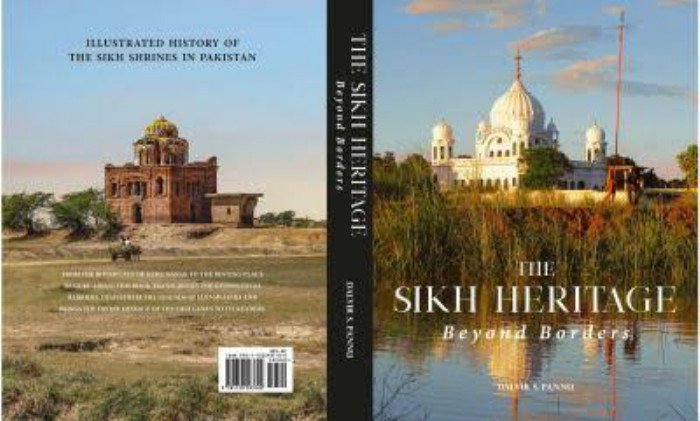

The Sikh Heritage: Beyond Borders

By Doctor Dalvir Singh Pannu, San Jose, California, USA.

Published by: Pannu Dental Group, 2019 – www.thesikheritage.com

Printed by: Copy well, Canada. Hard Bound Edition, Pages 416; Price: $95

Reviewed by:

Bhai Harbans Lal, Ph.D.; D.Litt. The University of North Texas.

It has been many years since I had first met Dr. Dalvir Singh Pannu personally during my California visit. I had heard of him earlier as an established dentist in that area.

During our very first conversation, I found that my new acquaintance was fired up to serve his faith as well as his faith community. He was particularly proud of his and his family’s affiliation with Guru Nanak. He was inspired to research and disseminate his Sikh Heritage. Little that I knew that he would take off time from his professional practice to undertake this extensive project under review.

Thus, the book under review is not just writing down on a subject but undertaking field trips to personally research data to build this volume. And he did an exceptionally great job.

As the author told me that he wanted to not just walk but in reality, talk and listen to the streets, bricks, buildings, and their ruins, as well as to the neighbors who had personally experienced the presence and the gossips about the Sikh historical places. Plus, he extensively searched old literature, historical records, and the observations of those who recorded their search on the subject of his interest.

In painstaking research that took Dr. Pannu, and often his family, more than a decade, truly going deep into the Sikh scriptures, researching into Sikh history, and reviewing compilations of Sikh legends and hagiographic literature. He methodically constructed everything that went into his book under review.

Dr. Pannu touched the earth on which Guru Nanak in his 10 lives walked, talked, and lived to touch peoples’ hearts. It is there that the Nanak Panth evolved and established. There, the author explored the bricks and mortars, the mud, and the labor that went into preserving the biography of Guru Nanak and his successors.

Dr. Pannu’s pursuit resulted in a veritable encyclopedia of Sikh shrines and places lost to the community. The Sikh nation left this irreplaceable heritage beyond the Radcliff border in Pakistan after the bloodstained separation of India and Punjab in 1947.

The author began by reminding the readers of the pains and sacrifices that innocent people of all faiths and communities suffered as a result of the 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent. He quoted renounced historians and politicians to describe the extent of this unparalleled dread suffered by the Punjabi population of Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims all alike.

The Sikh sufferings were unique as their major population was born, lived, and flourished in the areas given to what would result in the formation of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The Sikhs would become a meniscus and vulnerable minority overnight.

Dr. Pannu starts Chapter one appropriately to begins with Nanakana Sahib meaning the sacred birthplace of Guru Nanak but in implied meaning as the birthplace of Sikhi_sm.

Guru Nanak was the founder of a new thought, a new community originally known as Nanak Panthis. His followers, Nanak Panthis, flocked to him everywhere he visited. That led to the formation of a community of Sikhs, that originated from Sindhu (Hindu) civilization East of the Sindh River Valley, and a community of Mureeds that originated from Turki (Turkish) civilization, West of the Sindh River Valley. These civilizations are referenced in the Sikh scriptures as below:

The Guru Granth described them through the verse as:

ਹਿੰਦੂ ਤੁਰਕ ਦੋਊ ਸਮਝਾਵਉ – SGGS, p. 479

Guru’s teachings attracted people of both, Sindhu civilization

(later known as Hindus) and Turkish civilization (Turks, Abrahamic religions).

Subsequently, the Sikh historian Bhai Santokh Singh while describing the congregations of Guru Nanak in Kartarpur confirmed it as:

ਹਿੰਦੂ ਤੁਰਕ ਅਦਕ ਚਲ ਆਵਹਿ | ਸ੍ਰੀ ਨਾਨਕ ਕੇ ਚਰਨ ਮਨਾਵਹਿ |

ਏਕ ਮੁਰੀਦ, ਸਿੱਖ ਇਕ, ਹੋਵਹਿ | ਦਰਸਨ ਪਰਸਨ ਕਲਮਲ ਖੋਵਹਿ |

Hindus (Sindhu civilization) and Turks (Abrahamic religions), both, were flocking to

the feet (teachings) of Sri Guru Nanak. The former became Guru’s shishya (pupil)

or Sikhs, and the others became Guru’s Mureeds, ones who seek.

Then, rightfully, the book under review is dedicated to the 550th Birth Anniversary of Guru Nanak. And Guru Nanak’s legacy is remembered in the book’s Dedication sections as:

ਸਤਿਗੁਰੂ ਨਾਨਕ ਪ੍ਰਗਟਿਆ - ਮਿੱਟੀ ਧੁੰਦ ਜੱਗ ਚਾਨਣ ਹੋਇਆ

ਜਿਉ ਕਰ ਸੂਰਜ ਨਿਕਲਿਆ ਤਾਰੇ ਛਿਪੇ ਅੰਧੇਰ ਪਲੋਇਆ

With the emergence of the true Guru Nanak, the mist (of ignorance)

cleared and the light _(truthfulness) spread all around.

As the author acknowledged that he had to gather knowledge from other than Sikh literature often about Nanak-Panthis and their religion as well as Hindu religion and Islamic beliefs.

In the book, Dr. Pannu acknowledged over 150 authors, scholars, and historians from many religions for their input and critiques. Among them are included Sikh scholars ranging from Bhai Santokh Singh of yesterday to Bhai Vir Singh of today.

The resulting exhaustive work includes a comparative analysis of the Janamsakhis associated with Guru Nanak Dev with similar sakhis (tales) from other faiths. Examples are Kaaba shifting its place, cobra spreading hood to shade, and prodigy pupil revealing the mystical significance of the alphabet to the schoolteacher (pages 24, 38, 42).

The evolution of Gurmukhi script from the times of Guru Nanak Dev to Guru Arjun Dev is explained in the chapter Gurdwara Patti Sahib (page 40).

The pre-partition revenue records have been included to comprehend the land disputes during the Gurdwara reform movement. For example, the author details in the chapter on Gurdwara Kiara Sahib,

"Mahant Fauja Singh was in charge of Gurdwara Kiara Sahib during the Gurdwara Reform Movement and his partners in landholding were Ujjagar Singh and Mahantani Inder Kaur. The Gurdwara property included 15 murabba (1 muraba equals 25 acres) of land in the Village of Darria. After losing their case at the High Court, the Mahant and his partners were evicted from the property on June 17, 1936.” (page 46).

The author with his pioneering research of new pieces of evidence, backed by more than 750 endnotes citations has respectfully contradicted the findings of many prominent historians in a few cases. In other cases, he confirmed many reports by many authors.

For example, among stories that have been challenged in the book include Karam Singh's investigation of Bala Janamsakhi (page 61), Khushwant Singh's claims about Guru Arjun's martyrdom, Kapoor Singh's viewpoint about Mujjaddid Ahmed Sirhindi (page 239), Kavi Santokh Singh’s narrative about Sri Guru Teg Bahadur’s visit to Golden Temple Amritsar (page 181), and Syed Muhammad Latif’s assertion that Bhai Bidhi stole the “Emperor’s” horses (page 277).

For understanding the circumstances leading to the martyrdom of Guru Arjun, the reader can find new evidence included from Bhai Banno Prakash, Dhakhirat al-Khawanin, and A contemporary Dutch chronicle of Mughal India (page 230). In the chapter Gurdwara Dehra Sahib, a striking similarity of “wah-dat al-wujud” doctrine by Iban Arbi to Sikh philosophy has been explained. In the same chapter author tells that after the martyrdom of Guru Arjan, there was a large gap of more than a century until Chandu’s name appeared first time in the written history, in the antki sakhi of Parchian Sewadas.

The Sikh Misls’ timely help to the subjugated Hindu community at large during the mid-eighteenth century has been poetically quoted from the accounts of Sri Guru Panth Prakash. The author tells that “from there on, after ousting the Afghans in Sialkot, the Khalsa was on a winning spree, which eventually led to the establishment of Sikh rule throughout the region of Punjab”. (page 90-91)

Many topics in this book call for a need for mutual academic research between Pakistani and Indian historians. Some examples are Muhammadipur (where Meharban Janamsakhi was written), Baoli Guru Amar Das ( where the third Guru articulated the hymn ਲਾਹੌਰ ਸਹਰੁ ਅੰਮ੍ਰਿਤ ਸਰੁ ਸਿਫਤੀ ਦਾ ਘਰੁ (The city of Lahore is a pool of ambrosial nectar), the shrine of Mai Rajjo and Mai Dharmo, the village Hehar of Pirthi Chand, Chubacha Ram Rai, Sain Mian Mir Mausoleum, Wazir Khan mosque and shrine of Hazrat Abdul Qadir Gilani Sani.

A special focus has been added to establish the historical significance of sites where the rare handwritten manuscripts of Sikhs’ sacred scripture Sri Guru Granth Sahib were kept in pre-partition times. They include villages of Sharenke (pp. 176), and Jambar kalan (pp. 142).

Through many research examples included in the book, the readers of The illustrated History of the Sikh Shrines in Pakistan and Guru Nanak’s biography contained in the book will get a good taste of the way history is made and recorded.

In a beautifully designed Table of Contents, the book is shown to be based on the narration of 84 historical monuments or places in 6 districts of Pakistan, namely, Nankana Sahib, Sheikhupura, Sialkot, Lahore, Kasur, and Narowal. The maximum number of Gurdwaras (42) are listed under the Lahore district which has 84 historical places including gurdwaras.

In an astonishing discovery, this book marks the site, Gurdwara Shahid Ganj, where Bhai Taru Singh was scalped (pp. 306) a separate shrine, from the location of Gurdwara Shahid Asthan Bhai Taru Singh in Hanuman Koocha. There the severely wounded Sikh martyr took his last breath (pp. 316).

The book also reveals the mixture of different expressions of various faiths of the Indian sub-continent on Sikh architecture.

For example, A Ganesh Chakar inlay of black color on the wall of Gurdwara Sahib Daftuh (pp. 165) has been noticed by the vigilant explorer while compiling this book. The structure of a shrine in District Kasur appears to be a Hindu temple at first glance, but the photo of the Gurmukhi inscription, as provided in the book, reads, “Gurdwara Bawa Ram Thaman. The Singhs of village Daftuh got this door frame installed.” The Jhingar Shah Suthra Samadh showcases the Upanishad Shlok in Sanskrit and a composition of Guru Nanak in Devnagari written next to each other (pp. 347).

In another chapter discussing village Manak, the tedious legal struggle among Udasi Maha Mandal and Shromni Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) is explained. The legal documents of the British Raj period provided in the book demonstrate the depth of research that the author went into while producing his work.

The court case at Manak revolved around the point that no Sikh guru visited this site, making the shrine a point of contention between Udasis and SGPC. The author also humbly clarifies the mistakes made by many previous works that had mistakenly associated this Gurdwara with Guru Nanak Dev. Using the appropriate choice of words, the author concluded the current dilapidated condition of this shrine as follows: “It may also be pertinent to mention that while the gurdwara lies abandoned since 1947, neither the Udasis’ nor the SGPC staff have expressed an interest in the shrine anymore”.

In many instances, the book provides the same version of multiple sources so that readers can make their own analytical judgment. For example, the account of Gurpartap Suraj Parkash Granth (Raas 11-21,22) is pitted against Bhatt Vahi Multani Sindhi about the visit of Guru Teg Bahadur to Harmandar Sahib, Amritsar in 1664.

Pothi Sachkand (Meharban Janamsakhi) providing a different account of Guru Nanak’s birthplace as “Chahalan Wale” than other prominent janamsakhis accounts of the birthplace as “Talwandi” is yet another example of analyzing contradictory statements side by side throughout the book (pp. 188).

Through the chapter regarding Buddhu Da Awa, the author portrays the Sikh tradition in which Buddhu was cursed by a Sikh of Guru Arjan, causing his bricks from his kiln to remain unbaked. However, according to a contrary legend added in the same chapter, Buddhu Shah was in fact cursed by Abdul Haq, a follower of Sain Mian Mir (pp. 223).

Illustrating the rescue site of horses by Bhai Bidhi Chand, the author presents the contrasting versions of Dabistan-I Mazahib and the Sikhs’traditions (pp. 277).

The Persian records of Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh and Muntakhab al-Lubab were also pitted against the Guru Ki Saakhian about the apparent meeting of Dara Shikoh with Guru Har Rai (pp.296).

The accounts of Udasi writers provide varying versions of Sikh traditions, which have been described in detail in the chapters of Gurdwara Sacha Sauda and Gurdwara Tahli Sahib (pp. 76, 208-211).

The book under review records an overabundance of Gurmukhi inscriptions inside the Sikh monuments left in Pakistan. They have been translated into English by the author for convenience. Emphasis has also been placed on buildings with rich frescoes and artwork, that would preserve them in print as many of them are on the verge of crumbling.

Despite the general notion of Sikhs to be valiant warriors, not much has been said about their wits and intellectual capabilities. The author, on the other hand, was able to capture this aspect of the Sikh community when he described the demands the Sikh community put forward before Zakaria Khan. He was advised that his sufferings may be alleviated if his scalp is struck with Bhai Taru Singh’s shoes. (pp. 316).

Taking readers back and forth between ancient and modern history, the same chapter covers the ancient accounts of Prachin Panth Prakash as well as modern details of Shudhi reconversions performed by Giani Dit Singh and Dr. Jai Singh at this gurdwara during the Singh Sabha Movement (pp. 316-317).

A multitude of community’s attempts to associate various well-renowned people with their own clans is seen by the claim of Bhai Mani Singh to Panwar Multani, Kamboj, Kahna Kachha, and Dulat (pp. 318). Gurdwara Bana Jamai Singh Ji Kahna has a strong connection with the Kuka movement.

The book includes many interesting facts supported by literature citations. How the shrine of Amritsar was under mortgage with Sahib Rai Naushehria, when Jassa Singh Ahluwalia secured it by paying back the stipulated sum (pp. 343). The author provides the name of Gurdwara Patshahi III Tergay as Jhaari Sahib, yet another fact mentioned for the first time in post-1947 literature.

Additionally, in the chapter are included Gurdwara Mal Ji Sahib Kanganpur and Gurudwara Manji Sahib Manak Deke.

The author’s hard work and extensive research are demonstrated through his comparative analysis of Puratan Janamsakhi, Sri Guru Tirath Sangreh, Gurdham Sangreh, and Gurshabad Ratanakar Mahankosh.

The author has continuously connected the dots of history’s timeline through the chapters built upon one geographical location per chapter. For instance, in Gurdwara Patshahi VI and Patshahi VII Ghalotian Khurd, the author puts together the narratives about Sri Guru Har Rai, Bagh Mal (father of Veer Haqiqat Rai), Dr. Diwan Singh Kalepani, and Bhai Dyal Singh, the poet who wrote famous Fateh Namah (pp. 108-111).

The author selected for inclusion the places that had a distinctive story to tell. However, the author admitted right in his Preface that he covered for his venture the number of sites that far exceeded those that could be accommodated in a single volume. The additional data still on his digital storage may well be published in the foreseeable future pending the interest and input generated by the esteemed readers of this first volume.

I am sure that it will happen, and we look forward to furthering publications from Dr. Pannu.

The book ends with an extensive list of Abbreviations and citations to make it easier to find whatever one is looking for.

The book that emerged from Dr. Pannu’s work, certainly, is a rich panorama of images and sites, historical facts, and references interspersed by scriptural quotes and historiographic legends. The quality of the photos and the text are of high and professional excellence. The book even provides the longitude and latitude of important sites at the beginning of each chapter, so that the reader may virtually visit the locations through Google Maps at the same time that one is reading the book.

The book is highly recommended for academicians and researchers interested in the Sikh history of Pakistan. It may also find an interesting place for reading to the family, Sikh youth, and some three hundred million admirers of Guru Nanak’s teachings spread everywhere in today’s world. The readers of The illustrated History of the Sikh Shrines in Pakistan and Guru Nanak’s biography contained in the book will get a good taste of the way history is made and recorded.

Harbans Lal

[email protected]