Few are the occasions when we interact with a text that captures the living pulse of an age, making a bona fide redemption plausible. Rendering a sense of hope to explore self-knowledge of a society and how a worldhood is constituted through the interactions of its cultural, social, ideological, ethical, and political sensibilities, one is drawn towards the central axis of its meta-temporal makeup. This is perhaps, how the narrative in the plot of a recent novel, or a medley as the author Prof. Puran Singh would call it, Bhagirath published after a century of its authorship, has brought forth the engaging nuances of Punjabi life and its inner dynamism.

This is also pertinent in the backdrop of recent Netflix series, Heeramandi, which coincidentally aligns with same timeframe, depicting the lifestyle of nautch girls of Lahore. The series has sparked a significant interest in the sensibilities of Punjabi lifestyle, creating a sensation both in India and Pakistan. However, recounting the complex nature in which social ethics are constituted in the vividness of narration and profound details that go much beyond the section of society of nautch girls, Bhagirath presents subtle accounts of social influences that shape the psychological makeup, intuitive impulse, aspiration, and imagination of a society and its people. Therefore, even though the novel offers a story of the past traditions, it also evokes interest in metaphysical underpinning of human sensibilities, which starves in absence of a saintly touch to recuperate its self-consciousness. In that background, let us take a quick glimpse of its plot.

While there are many subplots that run in parallel to the main story line, the character of Bhagirath Mull, a pious man, remains central to its narration. While undertaking routine chores of his life as a railway clerk, he is often found helping his fellowmen. One of his friends, Lala Sunderdas, who is about to die, asks Bhagirath Mull to take care of his son Ramlal, studying in England, and help him settle down in Punjab after his return. Upon his return, Ramlal marries Lara (also known as Lajvanti), who was educated by her father-in-law, Sunderlal, during Ramlal’s absence. Sunderlal did this to ensure that Ramlal and Lara were compatible both educationally and socially. Educated as a barrister in England, Ramlal is ambitious and begins to take interest in emerging political situation as the idea of an independent nation started gaining traction, particularly amongst young, educated elite of the time. His house became a center of evening discussions where he plans to start his own newspaper.

He travels to Maharashtra pursuing his mission, where he meets and falls in love with poetess R.B. Driven by his intense feelings for R.B., he ends his relationship with Lara, who had been ill for some time, and marries R.B, with whom he has a son. Ramlal’s actions deeply upset Bhagirath Mull, who confronts and rebukes him for his infidelity. Bhagirath remains kind to Lara and adopts her as his daughter. Meanwhile, as the time passes, R.B. realizes her mistake and asks for forgiveness from Lara. Later, Ramlal is subjected to imprisonment, because of the rumors of his actions against the government. After sacrificing all her belongings to secure Ramlal’s freedom, R.B. roams the streets of Lahore, now stripped of all she once owned. Considering the emerging situation, Bhagirath Mull, despite their differences, makes efforts to secure Ramlal’s release from imprisonment while trying to keep his promise to his late friend. After his release the family settles in Jullundur, away from Lahore. Meanwhile, cultivating a sense of higher realization, Lara is profoundly moved towards deeper insights of self-realization. The story concludes with a sublime scene, where Lara, along with a few pious devotees including Bhagirath Mull, realizes that the ebbs and tides of mundane life are merely a part of soul’s journey to understand a true meaning of Self beyond grudges, envy, and materialistic pursuits. Throughout the story, Bhagirath Mull, an embodiment of sainthood, transcends the desires of mundane life, remaining committed to respecting the flow of life in Divine order.

Taking a step back from the subtle details of the broader plot, it is quite noticeable that Prof. Puran Singh weaves a rich tapestry of life in colonial India, particularly in Punjab through this unique novel Bhagirath. It is indeed the first novel of its kind, with such rich narration and fine details that it makes an era and its life pulsate organically within the text. Beginning with the landscape and architectural mapping of Lahore city, the author vividly portrays the socio-economic conditions, behavioral patterns, plight of the nautch girls, traditional sensibilities and attitudes, and the shifts in these attitudes and behaviors with the rise of an educated elite exploring new political sensibilities. The story delves into intellectual and public debates on idea of nationhood following the colonial encounter, providing a detailed narration of influences reshaping the socio-political and economic fabric of Punjab. The subplots in book, including depictions of simple village life free from ideological objectifications, the wisdom of vegetable sellers, traditional methods of running industries and economies where industry owners maintained organic relationships with workers, and the exploitation of workers by emerging industrialists based on their religious identities, provide a comprehensive and refreshing glimpse into the life of the author’s period. Additionally, through many conversations between various characters, the novel renders a lucid portrayal of the subjective dynamism arising from the encounter between ‘tradition and modernity’.

This shift from tradition to modernity, as Michel Foucault has pointed out in his famous essay What is Enlightenment?, is not merely a progress of history from one period to another, but constitutes a complex transformation in attitude, ideas, and even ideals associated with this shift. This transformation involves shifts in self-perception, driven by widescale endorsement of renewal of art, aesthetics, signs, symbols, culture, and behavior patterns, which in turn foster a process of reinventing oneself. Therefore, the hegemony of power associated with modernity cannot be attributed to any single entity; instead, it is spread across various interconnected networks that dexterously weave a narrative of an implied enlightenment. The story of new epistemes spearheaded with the idea of democracy ensured by a modern nation state triggers a vision of a free and liberal society that produces its own ethos of self and social conduct. The promise of the future attracts the attention of many like Ramlal, educated in the modern education system, who are enthusiastic to turn the next page in the history of mankind breaking free from the chains of the past. While remaining in a perpetual state of dynamism, new individual and social Ethics are formulated that are subjected to colonial structures of power.

The thematization of the tension between tradition and modernity is constituted through the idea of liberty that remains inarticulately embedded within the narration of Bhagirath. Besides, a close reading of the text reveals an acknowledgement of inherent stagnation of tradition, which is reflected in pleasure seeking hedonism despite the plight of nautch girls of Lahore, signaling a decadence of Punjabi culture. While positing a cultural exhaustion of Punjab, the author also highlights how Indian mind remains weak in shaping a truly sovereign world view. This weakness leads to a historical decline both in subjectivity and in terms of political fallout, which, as suggested, can be transcended by a sovereign, luminous, and intuitive imagination. This imagination is constituted in historical assertion of prophetic unfolding of the idea of Truth, illuminated and incarnated in Guru Gobind Singh. R.B., the poetess of Maharashtra, reflects on this through a broad historical perspective, penning a national anthem of India inspired by her intuitive insights. This national anthem epitomizes the essence of nationhood, reflecting a journey to uncover its soul. Although it remains grounded within its geopolitical boundaries, its spirit transcends ideological fervor, celebrating life in its purest form of true liberty.

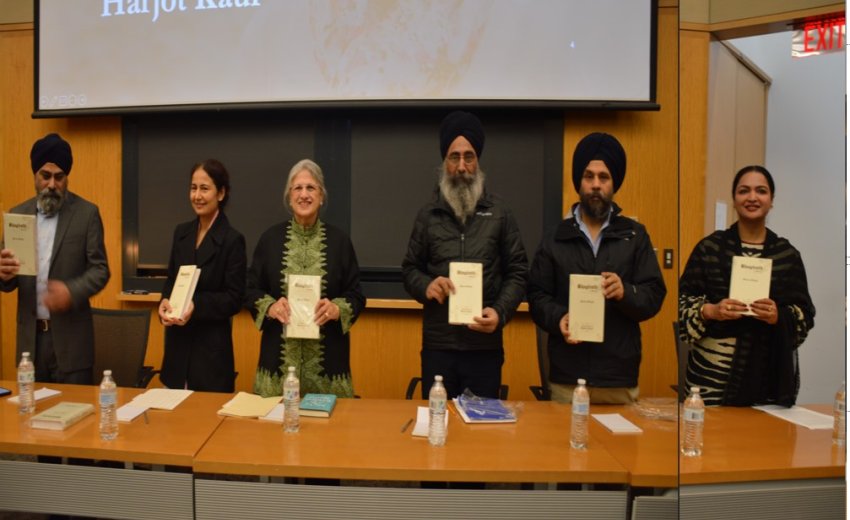

In conclusion, there are many layers to the unfolding of Bhagirath. While steering clear of outright demonizing or confrontations in the quest for truth across different contexts, it provides a lively narration of history, life, and culture, which can be analyzed through various academic lenses such as feminism, colonialism, postcolonialism, and nationalism. At its core the novel revolves around the culture of sainthood. It emphasizes that sainthood, as a reflection of Godhead in history, remains the heart of a realized social, cultural, and national life. In a way, it is a calling—an internal human urge to transcend blind materialistic pursuits and ideologically motivated political persuasions that bind the human mind into narcissism. Introduced by Harjot Kaur and released at Harvard University last year, a hub of transcendental philosophy, this text stands as one of the most historically pertinent forms of literary aesthetics that has come to light in our extraordinarily relevant times. Bhagirath, in a way, embodies the life of the past informing the present of its inherent soul.