Art, Faith, History, Culture & Science - this combination is a potent nexus, even explosive at times, as history tells us. But I have often wondered what the terms mean.

We all know what art is, or at least we think we know what it is. The definition of culture depends very much on what social stratum of society one comes from. A minimalist like me, who comes from the field of experimental biology, might think of culture only in terms of bacteria, or what transforms milk into yogurt. But bacteria don't buy tickets to the opera, so let's leave them aside.

We have added the passions of religion and science to the timeless mix of art and culture. In this goulash, while religion and culture have been intertwined throughout human history, science and faith have been at loggerheads with each other just as long.

I define art as any human skill that has a system of rules, and a talent whether inherent or acquired and which is honed by learning and practice. In its larger meaning, even cunning or trickery might be included for there is art to such skills, but for this exercise let’s leave them aside.

Culture goes beyond the cultivation of bacteria or tilling of land, to training, development and refinement of the mind. In other words, culture is the milieu in which the arts and sciences flourish, are nurtured and are practiced. Culture and art define each other. Thus, I have effectively freed art from its limiting association with certain specialized subjects of study, as opposed to other disciplines often labeled as sciences.

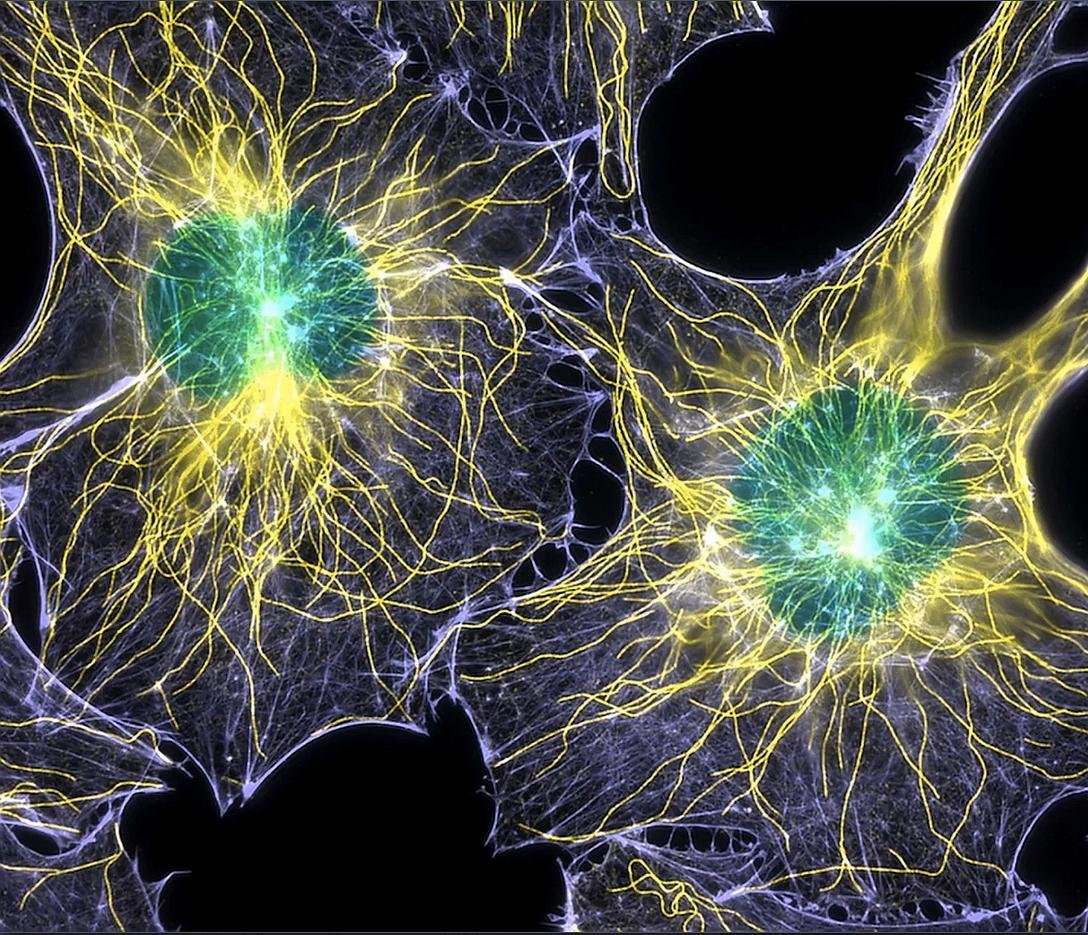

One must note, however, that while art creates culture so does science. The pursuit of science has its own rules, skills and logic. If art can be esthetically transcendent beyond words, just look at the equally mystical mind-boggling beauty and intricacy of the human body, or meditate on the structure of a cell revealed by a powerful electron microscope.

One must note, however, that while art creates culture so does science. The pursuit of science has its own rules, skills and logic. If art can be esthetically transcendent beyond words, just look at the equally mystical mind-boggling beauty and intricacy of the human body, or meditate on the structure of a cell revealed by a powerful electron microscope.

Many and variegated are the skills encompassed by art. Art doesn't just cover the range from Picasso, Dali or Rembrandt to Rodin, or from Bach and Ravi Shankar to Bhangra and hip-hop. It spans the labors of the cave man to the structures of atoms, molecules, and the ubiquitous DNA, from the making of a canoe or a two-wheeler to the design of a spacecraft that can explore the skies. The requirements of art demand the skills and mindset of a technologist and a scientist, just as the best scientists draw upon intuitive insights of an artist in designing and interpreting their experiments.

Art that comes from the heart speaks to our inner reality only when the head is also involved. Science is an intellectual exercise, but good science is never divorced from the heart. Science and art are interdependent but inseparable. Without some art to it, the best science is reduced to its unimaginative mechanics; without science, art becomes chaos, music becomes noise.

Think of the riots that occurred all over Europe and in parts of the Muslim world in 2005, triggered by a Danish newspaper editorial that included cartoons of Mohammed. And don’t forget how angry many Christians were in the 1990’s over a photograph that depicted a crucifix submerged in a glass of urine, and a painting of the Virgin Mary featuring a three-dimensional breast made of elephant dung. Litigation was mounted against the artists; museums lost their grants and politicians jumped into the fray with both feet to ride the crest of public outrage.

So why am I wading in such troubled waters where angels fear to tread?

A few years ago, an exhibit of early Sikh art opened at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City. Although nearly three million Sikhs now live outside India, from where they originated, and close to a million make their home in North America, where they have been for over a century, it was only the sixth museum-quality art exhibit on Sikhs and Sikhism outside India. I am counting here a collection on Sikh immigrant history at the Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle, the unexcelled displays of art at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Smithsonian in the capital city of the United States, San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and last but not least, the Rubin in New York.

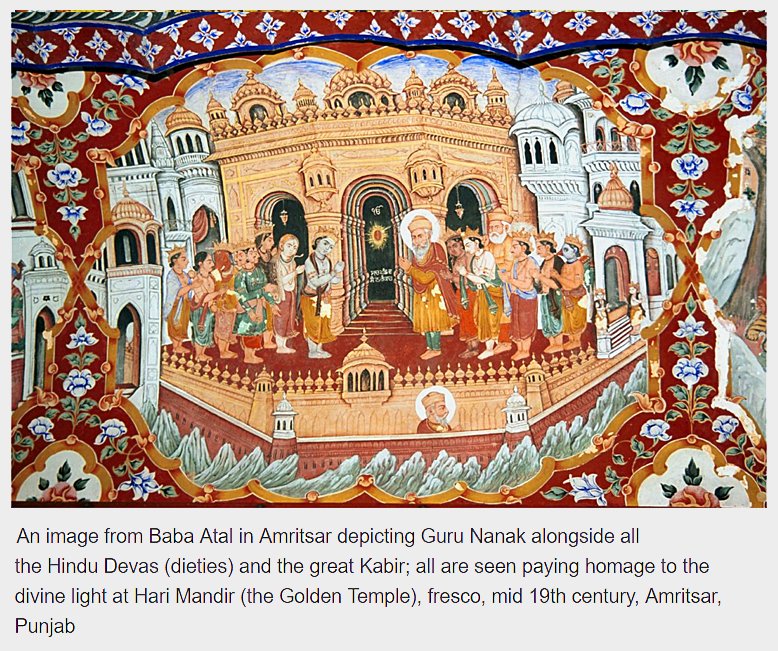

In the weeks preceding the exhibit I was at a meeting where the Rubin Museum’s art experts presented the images and paintings that might be displayed at the exhibit. One piece portrayed the founder of the Sikh faith, Guru Nanak, along with the Hindu pantheon, paying obeisance to Vishnu, the Hindu deity. Given the fundamentals of the Sikh faith and Guru Nanak’s own teachings, it is not even remotely possible that such an event actually occurred. Clearly, artistic imagination collided with and overrode both faith and history.

To the Sikhs, this image seemed to cast Sikhism as a mere sect of the much larger and older Hindu practice. This would deny Sikhism its own identity, something that has been a cornerstone of its belief during its entire existence of over 500 years. The Sikhs at the meeting were the patrons and community leaders who were underwriting the exhibition. They were visibly offended. Art like this, they insisted, would lead to serious misinterpretation of Sikhism, and diminish its place as an independent, modern faith.

My position was to try and bridge the gap. The matter resolved itself when that 18th century painting failed to arrive from India but, to my mind, the issue demands a conversation. Many of my attitudes to art coalesced during that meeting and subsequent conversations with Dr. Caron Smith of the Rubin Museum. In my view, Dr. Smith, the co-curator of this exhibit, is a most engaging, generous, and articulate scholar, deeply steeped in art – its history and appreciation.

When I look at such paintings of the Gurus and of the Sikh faith usually from 200 years ago, my first instinct is revulsion. Is this the essence of artistic freedom? How could any artist or any thinking person so distort the Sikh message?

But then I wonder!

The Founder-Gurus of Sikhism lived when the cultural reality of India was largely Hindu while the dominant political voices were Muslim. The traditional Hindu medieval style of painting was very much alive, and the highly intricate Muslim Mughal style was at its zenith. The Gurus valued art and patronized artists. This is clearly borne out by the complex art and architecture at the Golden Temple, for example. Yet, our historical and traditional narratives insist that no Guru ever sat for a portrait or endorsed a representation made by any artist. Some writers contend that during the ninth Guru Tegh Bahadur’s life, one artist painted a portrait of him. If so, it has been lost and is no longer available. The Gurus or their contemporaries make no mention of any representation of any Gurus made during their lifetime. Perhaps they were afraid that their iconoclastic message would be diminished and they themselves would instead become the icons of a new faith.

Soon after the Guru period, in the early 17th and 18th centuries, rich patrons, and minor satraps of the day, who were attracted to the Sikh message, may have commissioned the artists who drew portraits of the Gurus. Now thousands of such pieces exist. Are they realistic? No more than the millions of “likenesses” of Jesus as a blue-eyed blonde-haired figure.

Guru-portraits may represent the skill, style, and state of mind of the artist, or they may embody the biases and demands of the art patrons of the day who commissioned the works. We may find it tawdry but even today, we can find plenty of Sikh “calendar” art in the villages of Punjab in which Guru Nanak’s “head and face” sprout from the torso of a cow. Remember that in the mainstream Indian “Hindu” mind the cow is sacred and Guru Nanak is revered. Hew McLeod published a collection of such “popular” Sikh art. In the urban centers of India, Sikh pop-art has become more palatable, largely through artists like Sobha Singh, and primarily via the efforts of the Punjab & Sind Bank.

Such art, based on the parables of the lives of the Gurus often adorns Sikh homes. But does it hew to history? Rarely. Is it true to faith? Hardly. Does it accurately record the physical attributes of the Gurus? Likely not. In fact, these and related issues are not important. What counts is the message that is from the Founder-Gurus, not their flesh that walked the earth.

Then why do early representations of the Gurus and their lives exist? Why do people want or value them? That brings us to the place of art in life. What is art and what it is not?

Art is imagination. It symbolizes the deepest faith, but art is not history, nor is it religion. Art remains an unexcelled window into a culture and people of a certain time – their deepest yearnings and how they reconciled their hearts with the world around them. The symbolism in art can enhance understanding. Often, we recreate history from such windows into the human condition. For example, the literary and artistic output on the Holocaust, such as Anne Frank’s account, or the diary of Samuel Pepys on 17th century London, are not necessarily faithful history, but remain unmatched as means to understanding it.

So, when you see Guru Nanak portrayed as donning a Sufi cap or in the company of Vishnu, Durga or any of the others of the Hindu pantheon, resist the tempting call to take up arms. Be not angry. Could it be that the artist (or the patron who commissioned the work) admired Nanak so much that he placed the Guru in the company of gods that he himself loved and revered? Remember also the principle of artistic freedom.

Sikh tradition tells us that at Guru Nanak’s death, his Hindu and Muslim followers quarreled. Each side wanted to follow the rites of its own religion; Muslims wanted to bury him, Hindus wanted to cremate him. History is silent on which side prevailed, but at Kartarpur, where Nanak breathed his last, two memorials stand, one erected by the Hindus, the other by the Muslims. To me this is not blasphemy but a supreme compliment to the life and teachings of Guru Nanak.

In a similar vein, some old artistic renderings show Guru Nanak wearing a robe inscribed with Koranic verses in Arabic on one half and Hindu shlokas in Sanskrit on the other. Neither detracts from Nanak’s message. In fact, in the presence of both, side-by-side, one can see the centrality and triumph of his teachings. It is like the fresco of God’s hand emerging from the heavens on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, or the portraits of God, with Jesus sitting at his right hand. Much of the art that represents the many faiths of mankind, including Sikh art, takes its life from accounts that are hagiographic at best. Even art that seems to distort history or misinterpret the message of the subject can acquire meaning and significance if we look at such artistic depictions not as history or religion, but as supreme compliments to these men of God.

I can envision an artist, some day, creating an imaginatively ecumenical, interfaith canvas showing God at his table surrounded by Vishnu, Jesus, Mohammed, Buddha, Moses, and Nanak. Surely, Ram, Krishna, Durga, Joseph Smith and Baha’u’llah, among others, would also find a place. I suppose the seating arrangement would reflect the artist’s personal bias or that of his patron; in today’s complex world, it would surely spark lively disagreement.

Surely, such art would not be history. Would it be good enough to deserve space in a museum? Well, almost a lifetime ago, when I was a young student new to this country and Sikhs were few and far between, an art-school teacher invited me to pose for a drawing class. I did and often felt awkward listening to the teacher and her students dissecting my posture or anatomy. Some students gave me broader shoulders than I have; others were unable to make the beard look as if the hair were emerging out of the skin. My main concerns were more prosaic: I wanted to remain clothed and, as a struggling student, wanted to get paid.

Muslims view with abhorrence any images of Mohammed or of God. Their art consists largely of geometric designs; they never allow any human to portray Mohammed on the stage or screen. The Jews create no likeness of God. I have recently learned from a Jewish colleague of ultra-orthodox Jewish communities that do not make or photograph an image of a male human. Why? Because Biblically speaking, Man was created in the image of God. Ergo making an image of man would be like creating an image of God, and that is not acceptable. I also add that many movies have displayed images of Moses without major protests. It is true that Orthodox Jews do not fully spell out the word “God.” Christians seem to have no such compunctions; they, too, realize that images of God are artistic renditions and not realistic. Hindus appear to have no limitations on artistic depictions of any of their large pantheon on stage, screen, metal, paper, or stone. Sikhs reject all iconic representations of God and artistic renderings of any Guru as well, yet artists’ conceptions of Gurus are commonplace. There is even one within the historic Golden Temple; its provenance remains undetermined.

I look at the early art on Sikhs and Sikhism as representative of its time and culture. A lot of it has the flowing lines and the subtle, muted hues of the Pahari and Kangra styles of Northern India. In these, the Gurus are mostly depicted as high-caste Hindus. But then some art shows the intricate patterns and technical complexity that are the hallmarks of Mughal miniatures. In such Mughal art, I see that the facial features, robes, and turbans of the Gurus are virtually indistinguishable from those of Mughal noblemen. In the more recent Sikh art of the 20th century, one can also see Western influence in technique, style, form, and themes. Punjabi folk art always catches the eye for its vibrant earth colors. The first dedicated collector of Sikh art may have been Lockland Kipling, the father of Rudyard, as opposed to earlier colonial masters who pirated the riches of Punjab, a la Lord Dalhousie.

The Gurus lived in colorful times and, throughout memory, the history of Punjab has been eventful. The collectors, patrons and creators of early Sikh art were largely unschooled in Sikh history and religion. Perhaps they were not much better than most of us who belong to the “I know what I like” school of art.

Art may not always be true to faith or capture what T. S. Eliot termed “the contrived corridors and cunning passages of history,” but it continues to give expression to a people and to the passion in their lives.

Art and truth are intimately and inseparably enmeshed. As Picasso said, “Art is a lie that makes us realize truth.”