Watched by scores of eagle-eyed students, the two younger combatants use elegant curved swords and small circular shields to attack a taller and older man who is armed with a long double-edged blade and a simple dagger. Each time his opponents bring their weapons down, the lone warrior nimbly dodges the blow by sidestepping away or deflecting it back on to one of his opponents.

After a brief pause the tall man walks forward, runs a hand through his thick beard and announces with a slight hint of a Black Country accent: "The next technique I'll teach you is one that can break both a man's arms in just three moves. In real life of course, once you've broken the first arm your opponent is not getting back up. But when you're practising it's best to learn how to break both."

The martial art that the men are practising is shastar vidiya – a now little-known fighting technique from north India that virtually died out when the British Raj banned it after the final, bloody defeat of the Sikh empire in the mid-19th century.

While Chinese and Japanese fighting forms such as kung fu and ju-jitsu have become national institutions, shastar vidiya has languished alongside many of India's fighting techniques as a forgotten art form.

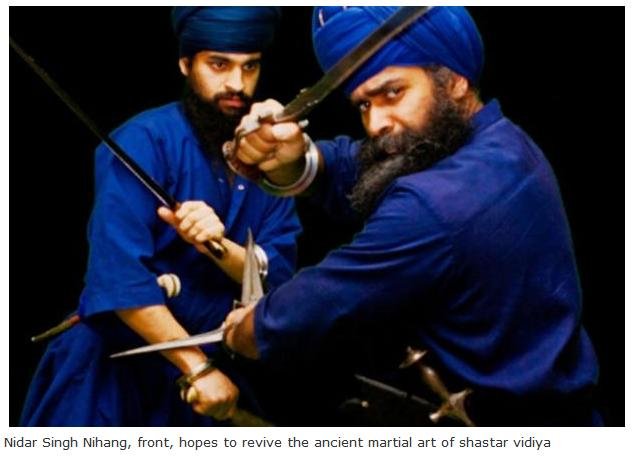

But one man is determined to bring it back from the brink of extinction. Nidar Singh Nihang is a 41-year-old "gurdev" (master) who has spent 20 years studying the secrets of shastar vidiya in order to pass it on to younger generations. It is a journey that has taken him from being a food packer in a Wolverhampton factory to one of the world's top authorities on ancient Indian fighting styles. Now he is looking for young apprentices willing to devote their life to learning the secrets of an art that he believes risks dying out altogether.

"Most people who practise Indian martial arts nowadays are simply learning the toned down exhibition styles that were allowed by the British," he says. "Unless we start teaching the original fighting styles they will be extinct within 50 years. I want to find two or three sensible, intelligent and tolerant young apprentices who can pass on what I've learned to future generations."

That a British citizen is trying to resurrect shastar vidiya by teaching it to young British Asians is more than a little ironic given the history.

Although shastar vidiya was widely practised across the subcontinent long before the emergence of Sikhism in the mid-16th century, it was the Sikh tribes of the Punjab that came to be the true masters of this particular fighting style.

Surrounded by hostile Hindu and Muslim empires who were opposed to the emergence of a new religion in their midst, the Sikhs quickly turned themselves into an efficient and fearsome warrior race. The most formidable group among them were the Akali Nihangs, a blue-turbaned sect of fighters who became the crack troops and cultural guardians of the Sikh faith. As Britain's modernised colonial armies expanded across the Indian subcontinent, some of the stiffest opposition they faced came from the Sikhs who fought two bloody but ultimately disastrous wars in the 1840s that led to the fall of the Sikh empire and allowed Britain to expand its Indian territories as far as the Khyber Pass.

Astonished by the ferocity and bravery of the Akali Nihangs, the Punjab's new colonial administrators swiftly banned the group and forbade Sikhs from wearing the blue turbans that defined the Akalis.

Sikh warriors were quickly given rifles and drafted into Britain's armies. The practice of shastar vidiya went underground and was nearly forgotten. In its place, the British allowed and encouraged "gatka", a ceremonial and toned-down version of shastar vidiya which is widely displayed during Sikh festivals today. Now Singh Nihang hopes he can make shastar vidiya as widely practised as gatka.

In one corner of the gymnasium where Singh Nihang is teaching his class an array of weaponry has been ceremonially laid out on the floor. Students begin learning how to fight with relatively harmless wooden sticks but those who show a particular finesse and dedication are allowed to practice with the kind of swords that once made the Sikh armies so powerful.

"This is one of my favourite weapons," says Singh Nihang as he picks up an undulating, serrated sword that looks uncannily like a snake. "It's very difficult to learn how to use, but it's also very difficult to fight against. The serrated edge confuses your opponent and allows you to sever muscle tendons in battle. It's a very nasty weapon.

"The key skill shastar vidiya teaches is deception. It's the blows your enemy never sees coming that do the real damage." For followers of shastar vidiya, the martial art is more than just a fighting style. Acolytes are expected to live up to strict religious principles and honour martial codes. The roots of shastar vidiya are not known but there is evidence to suggest that India's martial arts predate those from China and Japan.

Indian monks were the first to export Buddha's new teachings across the Himalayas and according to Chinese legend it was an Indian monk called Bodhidharma who first introduced martial arts to the famous Shaolin Temple in AD 600. Bodhidharma himself is thought to have come from south India where another indigenous fighting style known as Kalaripayattu has also undergone a recent renaissance.

One of Singh Nihang's top students is Iqbal Singh, a 39-year-old businessman from Slough who had spent many years looking for a master who might be able to reconnect him with his culture's fighting past.

"When I was younger I used to head down to the British Library where there are loads of manuscripts and books from the Sikh empire," he recalls. "I kept dreaming about travelling back to the Punjab to find a master and I always imagined he'd be some grizzled old man living in a hut somewhere. Instead, the person who seemed to know the most about these fighting styles was a factory worker from Wolverhampton."

In fact, it was thanks to the British Raj's obsessive bureaucracy that people like Singh Nihang have been able to reacquaint themselves with their ancestors' past. The physical technique of fighting was taught to him in the Punjab by a septuagenarian gurdev when he was a teenager but the vast records in the British Library and the V&A Museum enabled him to compile a history of the Akali Nihang warriors in a book called In The Master's Presence.

"That's something that has always amused me," laughs Singh Nihang. "It was British colonialism that nearly destroyed shastar vidiya, but it is also colonialism's obsession with book keeping that may save it."