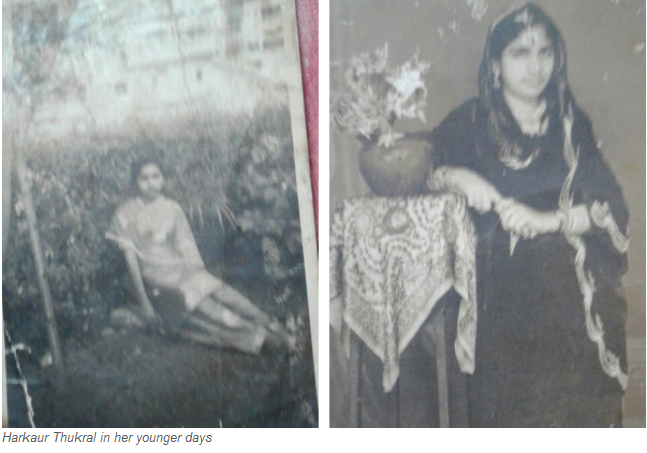

1947 Partition: A Sikh Survivor narrates her journey from Peshawar to Mumbai and why she harbours no animosity towards muslims

Fri, Aug 19, 2017: When India was Partitioned in 1947, lakhs of people crossed the border from Pakistan to India and vice versa. They left behind homes, belongings, best friends and sometimes even relatives as family members often disagreed on which country they should choose to stay in. Many of them came to Mumbai and even today, 70 years later, Sion is home to several such people. This is the story of one such Partition survivor.

Till 1947, Harkaur Thukral lived a stress-free childhood in Peshawar. Her father Jaswant Singh had a profitable business that he ran with his two brothers and Muslim partners. He had a fairly successful footwear store and a clothes shop in Rawalpindi, and a transport business that kept the family living a luxurious life in a huge bungalow.

"He used to wear these really good clothes with salwar and a kameez, waistcoat and a cap," recalls the 75-year-old at her home in Sion Koliwada. "The women in our family would travel in palanquins. We owned an entire building — known as tapu — in Peshawar."

Once the decision to Partition British India was announced in June, tensions began to mount. And by the time the Cyril Radcliffe-headed Border Commission's borders for India, Pakistan and East Pakistan were published on August 17, 1947, Peshawar had become dangerous for non-Muslims to stay.

Thukral's family had to move to India.

The extended family — Thukral's parents, her siblings, her grandparents and her aunts and uncles — took the fewest belongings they could carry and began their journey to the Indian border.

It was Jaswant Singh's Muslim friends who came to the family's rescue. Not only did they warn them in time, but they also drove the family in lorries to the nearest safe house.

"We called them chavni," Thukral said. "It was a huge house with glass all around it. And a lot of open area. It belonged to one Pratap Singh."

Their idyllic break in their arduous journey turned dangerous when one day, several attackers — allegedly Muslims — arrived at the farmhouse in tongas. Thukral distinctly remembers that frightful day.

"They sprayed bullets all around the house. Every glass shattered into a thousand pieces. Everyone ran helter-skelter. Some hid behind trees. My grandmother hid all the children under the bed. After a while, the attackers ran away. Miraculously, none of us were injured in the attack."

After that day, the families packed up and continued their journey to Rawalpindi station. They were supposed to take the train from there to Amritsar but things didn't go fully according to plan.

"My father was arrested for carrying weapons near Rawalpindi station," Thukral recalls. "He was sentenced to 14 months in prison in Pakistan."

With no choice, the rest of the family boarded the train and reached India safely.

While Thukral's extended family continued their journey onward to Mumbai, she, her siblings, her mother and her grandmother stayed back in Amritsar. They wanted to wait till Jaswant Singh was released from prison.

They were fortunate enough to find a place to stay but times were tough, says Thukral. "From living in luxury, we went to standing in line at the local gurudwara for food."

In the meantime, her father was being tortured at Rawalpindi prison. And again, their Muslim friends came to their aid. "They sent home-cooked food to my father in prison, wrote letters to him" and tried to make his time there a little more bearable, says Thukral.

When her father was finally released and was able to make it to Amritsar, Thukral and her family moved to Mumbai. Their situation improved remarkably and the extended family managed to buy a six-bedroom sea-facing apartment in Colaba.

Read Also: After 70 years, India gets its first Partition Museum in Amritsar

But the battle was not over yet. According to the terms of the Partition, those who crossed over to the other side could claim remuneration for the property they left behind. The Singhs hired a lawyer and again, with the help of their Muslim business partners, managed to get a hefty sum for their property. It helped them to kickstart their new life in Mumbai.

She admits that her family was one of the more fortunate ones. "So many people were killed during that time," she says. "I know of this woman who tied her dead daughter in a piece of cloth, weighed her body down with stones and sank her in the river."

There were many others who were forced by Muslim attackers to eat buffalo meat - a sin for Sikhs. "They chose to die rather than betray our faith," she says.

Despite all that, she harbours no ill-will towards Muslims or Pakistanis.

"They helped us a lot," she says of her father's Muslim friends. "They ferried us in lorries, they saved our lives. I don't have any animosity towards Muslims."

In fact, she smiles happily when she recalls the two trips she has made to Pakistan since then to visit the Nankana Sahib in Punjab province. "When our train reached the station, they offered us tea and there was band bajaa. It was like a party," she recalls of her first trip in the 1960s. Her group was received with much warmth and affection wherever they went.

Unfortunately, due to Pakistan's strict visa rules, she was unable to visit her ancestral home in Peshawar. And she doesn't believe that she ever will be able to.

Instead of regretting that fact of fate, she spends her time reliving her memories with others like her at the local gurudwara, shares them with the younger generation and proudly tells everyone she meets that she was born in Pakistan.

Her fondest possession is a phulkari dupatta her mother Gyankaur Nagpal brought from Pakistan during Partition. It is more than a hundred years old, she says. She stores it safely in her cupboard and takes it out often to run her hand over it.

"When I die, it will cover my dead body."